Electronic Lebanon 7 April 2008

Destruction of Nahr al-Bared’s old camp as captured by Al Jazeera English’s cameras.

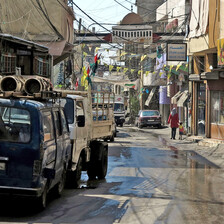

In the afternoon of 3 April, Al Jazeera English’s film crew along with personnel from the Lebanese security apparatuses appeared in Nahr al-Bared’s Majles Street. The Lebanese army and security apparatuses have so far forbidden any filming or photographing in Nahr al-Bared. At the various checkpoints inside and outside the camp, people are searched for cameras and found equipment is subject to confiscation. Journalists are generally not allowed to enter the camp and even if they get the necessary permission, soldiers or security apparatus agents must escort them.

Al Jazeera English’s resulting three-minute-long report entitled “Refugees return to Nahr al-Bared” focuses on the planned work to clear out the destroyed camp, the poor infrastructure camp residents are trickling back to find, and the camp reconstruction committee’s plans to rebuild the camp in the next two years. These issues can be described as humanitarian concerns, and are indeed relevant ones that many refugees worry about, and which Al Jazeera English covers in a more or less responsible fashion.

However, the narrow humanitarian scope totally ignores the political dimension of the Nahr al-Bared situation. Al Jazeera English fails to mention the heavy presence and the (political) role of the Lebanese army and security apparatuses in the camp. The destruction of the refugee camp is presented as a “normal” byproduct of a military battle, the events and narrative of which are left unquestioned despite the widespread evidence of looting, intentional destruction and arson in the ruins of the houses. Also unasked is the question whether the seemingly systematic destruction is the result of politically motivated orders. Indeed, though the walls of many camp dwellings bear the telltale petrol stains, Al Jazeera English’s footage only includes structures where this destruction is not visible.

Al Jazeera English reporter Zeina Khodr states in the broadcast: “Some 10,000 [residents who were displaced during the fighting] have returned to Nahr al-Bared over recent months, but only to homes on the camp’s outskirts.” Khodr fails to mention that many refugees are so far not allowed to return because access to the camp requires permission from the Lebanese army and security apparatuses. Many have not been able to obtain the necessary permits that would allow them to pass through one of the various checkpoints where Lebanese forces control all movement into and out of the camp.

Khodr goes on to report: “Behind these buildings is the area known as the old camp. It was reduced to rubble during last year’s fighting. And it remains closed while the army continues to clear ammunitions. Most of the camp’s residents, some 20,000 refugees [sic], used to live there, and they’re not returning any time soon.” Khodr’s words lead to the conclusion that the old camp was damaged to this extent because of the fighting between Fatah al-Islam and the Lebanese army. What the reporter fails to mention is that many houses were actually burned and demolished after the battle had ended, and when only the Lebanese army was present in the old camp. Additionally, it is not questioned how the whole of the old camp could have been totally leveled (not a single structure remains intact) during the fighting.

By not questioning or even stating her source when she says that the old camp is still inaccessible because munitions have to be cleared, Khodr ends up giving the Lebanese army the benefit of the doubt. Had she interviewed camp residents, they might have aired the fears shared by many that the army is only saying there might be unexploded ordnance as an excuse to intentionally prevent the opening of the old camp, and thus delay its reconstruction. Furthermore, it should have been mentioned that even in the rubble of accessible and therefore theoretically de-mined houses, quite a few unexploded ordnance have been found by returning refugees.

Through reports like these which limit their coverage to the humanitarian situation in the camp, Al Jazeera English and other mainstream media fail to report the full extent of the problems faced by Palestinians in Nahr al-Bared. Instead of engaging in critical inquiry, such reports merely accept and repeat the Lebanese government’s and army’s official version of what happened and continues to happen in the refugee camp. This, of course, is to the disadvantage of the 30,000 Palestinian refugees who once again find themselves homeless, robbed, humiliated and oppressed. What’s more, if the situation of Nahr al-Bared is left unquestioned, it lends itself to being repeated in one of the other numerous refugee camps in Lebanon.

Ray Smith is an activist with the anarchist film collective a-films, which has short films from and about Nahr al-Bared available for download on its website: http://a-films.blogspot.com.

Endnotes:

[1] The Al Jazeera report can be viewed at http://youtube.com/watch?v=vdYyhGtJ3Xg.

Related Links