The Electronic Intifada 9 March 2008

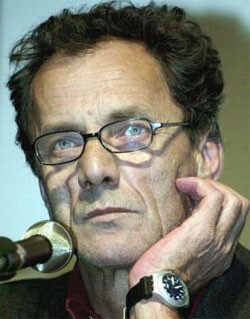

Filmmaker Mohammad Bakri

Jenin Jenin documents the aftermath of Israel’s April 2002 siege of the northern West Bank refugee camp, during which many of the residents were killed and a large part of the camp was leveled by bulldozers. Journalists were not allowed into the camp during the incursion and Israeli forces did not allow human rights organizations in immediately afterwards, and the film documents the destruction of the camp and the exasperation of camp residents during this time. Jenin Jenin co-producer Iyad Samudi was killed by Israeli forces shortly after the film’s completion.

In 2002 the film was banned by the Israeli Film Ratings Board but a year later the ban was lifted by the Israel’s high court after one year of media attacks against Mohammad. The attacks went on in the following years, through 2007, when five Israeli army reservists who participated in the Jenin massacre accused Bakri of defamation of character. Their names, their faces and their bodies don’t appear in the film. But what if they were in the film? If they were filmed committing shootings, demolitions, the massacre perpetrated with the consensus of the political and military chain of Israel, could we say that the images were a form of defamation? Photos and images, in a certain sense, are the icons of the object that they represent. But the point of the trial isn’t that it does or doesn’t show images of the soldiers in the film; the problem is that it gives voice to the survivors of Jenin.

During those days in the Auditorium of Rome we phoned a journalist who interviewed Mohammad Bakri, but we thought that the interview wasn’t enough. The issue was too complicated and serious to be dealt with only in an article. If Mohammad will be found guilty by an Israeli court in Petah Tikva he will have to pay 2.5 million new Israeli shekels in “compensation,” but more than that he will be forced to (but he won’t do so) declare that the film is not truthful — an intimidating precedent for all filmmakers (Palestinian as well as Jewish Israeli) seeking to document Israel’s crimes in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Bakri’s film is strong largely because it doesn’t rely on quantitatively stating how many executions took place in Jenin. Instead, it gives opportunity for the testimony a mother who says that one of her children was publicly executed, in front of her eyes. A disabled man expresses what happened to him and to his family during the siege, something more impressive and dangerous (for the soldiers who participated in the massacre) than quantitative data with which victims are mere statistics.

In response, we in Italy organized a campaign and contacted the most important Italian actors and filmmakers (including Giuseppe Bertolucci, Saverio Costanzo, Marco Tullio Giordana, Mario Monicelli and Moni Ovadia), asking for their signatures in a petition of solidarity with Mohammad. Some of them worked with Mohammad in the past, others just knew his story and recognized the same danger that we felt: the risk of something stronger than censorship, the risk that some soldiers responsible for a massacre would demand compensation from the director of a film documenting their crimes.

From 28 January until now, Jenin Jenin has been screened in more than 40 Italian cities and towns, with the fundamental help of the Association Hawiyya and its Project “Mediazione,” which aims to correct official media by providing alternative information from sevaral areas of the world. In Rome, Naples, Bologna, Siena and Turin, Mohammad Bakri told his story and participated in several debates on his trial. The screenings continue, with new towns and cities are organizing the events, lending an even wider audience to the film.

Nicola Perugini is one of the organizers of the Italian campaign of solidarity with Mohammad Bakri. The other organizers are Marco Dinoi, who passed away on 15 January (the campaign is dedicated to him) and Andrea Del Grosso of the Association Hawiyya of Siena.