The Electronic Intifada 10 October 2007

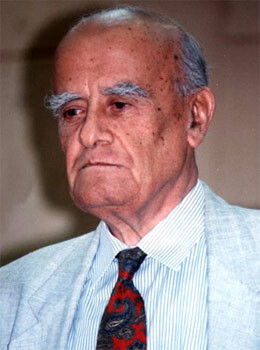

Haider Abdul-Shafi (PASSIA)

Here was someone who always managed to transcend factionalism and religiosity, tribal politics and self-serving ideologies, maintaining his principles through any external difficulties. He co-founded the Palestine Liberation Organization in the 1960s and went on to start the Palestine Red Crescent Society in Gaza in the 1970s. The resilient man led the Palestinian delegation to the Madrid peace talks in 1991 and in 1993 resigned the post after learning from his hotel radio that Yasser Arafat had reached a secret agreement in Oslo without consulting the Palestinian negotiators in Spain. Abdul-Shafi told me, in the first interview I had with him, that learning of Arafat’s secret deal from the media was a particularly embarrassing moment for him.

In the same interview in 2002, Abdul-Shafi also spoke at length about the Palestinian uprising, talks with Israel, internal corruption and division, democracy and more. Then aged 83, Abdul-Shafi displayed the spirit of an idealistic young fighter with unswerving vision, while also demonstrating the wisdom borne of five decades of selfless struggle and steadfastness. For him, despair was never an option. Internal unity, democracy, resistance on all fronts and dialogue on an equal basis were his ultimate goals. He seemed indefatigable, but his failing health became his most significant enemy as a few years later he was diagnosed with cancer and on 25 September 2007 he passed away.

I wonder if the aging worrier knew of the painful details of internal Palestinian strife, of shameful and mutual crackdowns on media and freedom of expression in the West Bank and Gaza, and of division at every turn in Palestinian life. The Palestine Abdul-Shafi left behind was not the Palestine that he had fought for with astonishing dedication.

In his fight, Abdul-Shafi was not afraid to speak his mind and criticize what disrupted the struggle for Palestinian unity and true sovereignty. He blamed Arafat and his associates for many of the post-Oslo disasters that had befallen his people, chastising the Palestinian leadership for capitulating at Oslo, for accepting far less than his people’s rights and aspirations demanded. He refused to take part in the “democracy” charade which instituted, among other pretenses, a parliament that had no authority, neither to defy Arafat’s will nor Israel’s, whose oppressive occupation only intensified after the “peace agreements” were signed.

Naturally, shortly after being voted into parliament Abdul-Shafi was the first to quit, lending his support instead to the Palestinian National Initiative that advocated national unity, democracy and clean government. He saw clearly that while Palestinians may not be able to control Israel’s actions, they were certainly capable of coordinating and correcting their own fallouts. This was really all that he asked.

In stark contrast, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas has decided to use the Israeli colonial project to his own advantage. Unlike Abdul-Shafi, who would have challenged Israeli domination with a collective Palestinian stance of complete cohesion at home and abroad, Abbas (dubbed a “moderate” and “pragmatic” leader by mainstream media) opted for the deadly option; he collaborated with the enemy. As Palestinians in Gaza are murdered at will, completely besieged and denied the most basic human rights, Abbas’s “pragmatic” advisors appear to have warned him against locking horns with the US and Israel. This approach overlooks the fact that defeatism has never helped an oppressed nation recover its lands, its rights and its freedom.

Unfortunately, Abdul-Shafi is no longer here to provide such timely reminders. The soil of Gaza has finally claimed him — the same way it claimed the bodies of many resilient Palestinian men and women, young and old. One can only hope that the spirit of Abdul-Shafi is now free to wander beyond the enclosed borders, electric fences and blocked military zones that turned that poor strip of land into a prison comparable in its isolation to that of Robben Island where Nelson Mandela and his comrades were held for many years.

As long as Abbas and many in his Fatah party remain busy concocting schemes to weaken their rivals in Hamas, and while both parties plot to fortify their political positions in what must be the most embarrassing media circus in Palestinian history, Israel no longer faces any serious resistance. Instead, Israeli politicians now face a different challenge — how to widen the gap between divided Palestinians. According to Avi Issacharoff in the Israeli daily Haaretz, the latest question is whether releasing Fatah leader Marwan Barghouti will help unify all ranks of Fatah, thus strengthening Abbas and accelerating the break-up of Hamas.

Unlike Abbas, Abdul-Shafi didn’t fail his people, despite all of the hardships he had to endure. He did all that a single person can do on his own, and more. Shafi’s funeral in Gaza reportedly united Palestinians of all factions. The man had spent much of his energy achieving this noble goal during his life. At least his death brought about a fleeting moment of unity, a reminder that such a thing is still possible.

In his speech at the peace conference in Madrid, 31 October 1991, Abdul-Shafi recited a verse of Mahmoud Darwish: “My homeland is not a suitcase, and I am no traveler.” At the time, my father’s home in a Gaza refugee camp was crowded with neighbors who had come to listen to the televised speech and they all cried silently in response. I am sure that those of them still alive have wept again, this time at the passing of the Palestinian icon of hope whose legacy, like his life, will always be cherished.

Ramzy Baroud is an author and editor of the Palestine Chronicle. His work has been published in many newspapers and journals worldwide. His latest book is The Second Palestinian Intifada: A Chronicle of a People’s Struggle (Pluto Press, London).

This essay was originally published by Palestine Chronicle and is republished with permission.