The Electronic Intifada 9 July 2007

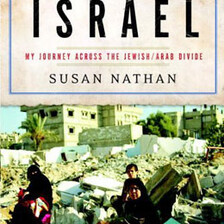

ISRAELI POLICE STATE: So-called Israeli democracy keeps tight control over Palestinians in the occupied territories. Here a border policeman argues with Palestinians at the main checkpoint between outside Bethlehem denying them entrance to the holy city of Jerusalem to celebrate the Islamic holiday of Leilat al-Qadr, 18 October 2006. (Magnus Johansson/MaanImages)

On Friday, 8 June 2007, my husband Ian flew to Israel. He is in fact on his way to an IT conference in Vienna, but we thought that it would be nice for him to make a short three-day detour to Tel-Aviv to visit my brother and his family and in particular meet my seven and five year old nieces for the first time.

At Ben-Gurion airport Ian’s Australian passport was confiscated with no explanation. He was taken to a small interrogation room and had to endure an intimidating questioning about non-existent Saudi and Lebanese visas in his passport. He was interrogated by a tough-looking uniformed female police officer while a non-uniformed agent watched. The officer asked him why he had Saudi and Lebanese visas. When he responded that this could not be his passport because he does not have such visas, she proceeded to ask him for the names of his father and grandfather. Despite the fact that Ian answered the question the first time, she repeated it three more times. By that stage Ian realized that they were trying to intimidate him and although he did feel some fear, he pointed out that she asked the same question several times and that he had already answered it. After about 25 minutes of this, Ian was finally released with no explanation and a feeble apology about delaying him.

As a former Israeli citizen with military training I am familiar with the psychological tactics used by the Israeli Border Patrol (MAGAV) and by the military. They deliberately try to intimidate their victim and keep him (or her) in a state of uncertainty — about what is going on, what it’s all about, where his papers are. They know that foreign nationals would feel profoundly insecure without their passports and that uncertainty would lead to fear and stress in most people. They also know that most people’s confidence would falter under such conditions and if there is anything to divulge, it is more likely come out then. Israeli officers are trained to watch body language, micro-expressions, perspiration, anything. The questions themselves are often just a pretext to induce stress so that they can watch their victim carefully to see if he has any secrets. They had Ian’s passport. They knew well that there were no such visas in it. (And you have to wonder: what if there were? What would have happened to him then? Australian citizens are free to visit any country they wish. But it appears that in Israel having the “wrong” visas in your passport turns you into a suspect. Of course we will never know whether the story about the visas was the real reason for his short detention.)

Israel and its apologists repeatedly portray Israel as “the only democracy in the Middle East,” a uniquely democratic regime in a non-democratic region. Somehow this is supposed to make us feel more sympathetic and justify our support of it. But Israeli democracy is a myth.

In my 27 years there I belonged to the Israeli mainstream. I was Jewish, Israeli-born and secular. I was an ordinary citizen who completed her military service, the quintessential Israeli, not involved in politics or activism of any kind. I minded my own business, worried about money, work, study, my own little life. I wasn’t a “trouble-maker” by any stretch of the imagination. Anyone who met me back then, would have assumed that I agreed with the prevailing Israeli ideology. And frankly, they would have been right.

Although Israeli daily life could be frustrating, particularly dealing with the bureaucracy, we felt safe in the knowledge that annoying as they might be, our authorities would never turn against us. In fact, the thought wouldn’t even occur to us. Because I was a member of this comfortable center of Israeli society, I was also ignorant of what Israel was capable of, and of what it could mean to not belong.

My first ever taste of this as yet unfamiliar “status” came around 17 years ago, when my ex-husband (also an Israeli) and I were planning to migrate to Australia, and were in the last stages of receiving our permanent residency. My ex, an engineer and a Captain in the army about to finish his contract, was told suddenly one afternoon, without explanation that he was to report to a certain location to have a little “chat” with someone from the Military Police.

Our plans to leave Israel were no secret. Leaving Israel is not a crime, and Australia was not on the list of countries that Israeli officers involved in secret military projects were prohibited from visiting or living in after the end of their service (yes, such a list exists). In any case, there was no reason for my ex-husband to suspect that this “chat” had anything to do with our plans.

He was taken to a small room and instructed to sit on a chair in the middle of the room. He was circled by a female Military Police sergeant who began by saying, “We found out that you are planning to migrate to Australia,” to which he replied “So? It’s not a secret.” She responded aggressively that he was to shut up, and that she was asking the questions. She then proceeded to ask “Why are you leaving?” and, “Does your wife know that you are planning to leave?” Apparently the military found out about our plans from the police, while we were in the process of obtaining clearance for Australian Immigration. They would have known that both of us were involved. The questions were clearly not intended to be engaged with at face value. Initially, my ex started to respond to the point, but when he realized the absurdity of the situation he became annoyed. He then told the sergeant that he did not see the point of the conversation and unless she was accusing him of something, he was leaving. When she responded aggressively again, he stood up, reminded her that he was a Captain and she a Sergeant, and left the room.

In the absence of any information about this incident, we concluded that this was an attempt to intimidate us out of leaving Israel. Of course it relied entirely on psychology because the military had neither reason nor a legal way of stopping us.

Up until the army found out that we were leaving, my husband as a career officer and myself as the “wife of,” were treated with great respect in Israeli society and in the military. We didn’t just belong, we had an honored place. The choice of a female sergeant was meant to humiliate him (I mean no offense to females but this is the culture in the Israeli military). Whoever dreamed up this intimidation attempt wanted to show my ex that his rank and status meant little if he was choosing the “wrong” path. We were angry but mostly shocked that he could be treated like this just because we wanted to leave Israel. It’s one thing to encounter the disapproval of friends and relatives in ordinary conversations. It’s quite another to be the subject of a menacing questioning by the MP. Our decision to leave apparently placed us in a new position in society, outside that comfortable mainstream. When we finally left at the end of ‘91 we did so with a bitter taste in our mouths having seen a glimpse of an Israel we didn’t know.

Ask any Palestinian and they will tell you much worse stories — frankly, there is no comparison. Palestinians cannot help but be seen as outsiders, whether they are citizens of Israel or whether they are refugees in the Occupied Territories, whether they are children or adults, male or female. All Palestinians live under constant military and police surveillance. They experience nothing of the mythical Israeli democracy. “Israeli democracy” is something reserved only for the privileged and mostly ignorant elite, of which I was also a member, until I decided to leave. Palestinian citizens of Israel live under an arbitrary and brutal police state. Their dealings with Israeli bureaucracy are not just frustrating but can be outright dangerous.

The Palestinians in the Occupied Territories live under a Pinochet-like regime. They can and do disappear in the middle of the night. They are blindfolded, cuffed, beaten, humiliated, taken to unknown locations with no information given to them or their families, tortured physically and psychologically and incarcerated indefinitely, often without charges and regardless of whether they are guilty of anything. It is arbitrary and it can happen to anyone. This is a far worse version of the two incidents I described above but the basic principles are the same.

In a regime like that you don’t have to actually do anything wrong to receive this treatment. This is because it is not only designed to catch people who break the law, it is designed to be a kind of a warning, a hinted threat. It’s there to flaunt state power, show people how small and weak they are compared with the mighty state, and offer a taste of what would happen to them if they even think to go against it. In the case of the Palestinians such tactics are also designed to make daily life unbearable in order to break their spirit and intimidate them into leaving. After all, what Israel really wants is all the land but without the people, something that so many in the West still refuse to recognize.

Israel is not a nice country. It is a powerful police state founded on pathological paranoia with only a veneer of civility, carefully crafted and maintained for the consumption of those who still believe in the myth of Israeli democracy. Mainstream Israelis live in a fictional bubble that separates them from reality. If there is a democracy there, only this select group enjoys it — just like the conformist white population in old South Africa. Supporting Israel now is the same as claiming that South Africa under apartheid was an acceptable democracy. It also means abandoning the Palestinians, just like the world abandoned black South Africans (and white dissidents) for 45 long years.

Avigail Abarbanel is a former Israeli and a local psychotherapist/counsellor. She may be reached at avigail A T netspace D O T net D O T au