The Electronic Intifada 15 May 2007

No irony intended: The Jewish National Fund’s advertisement for the Coretta Scott King Forest

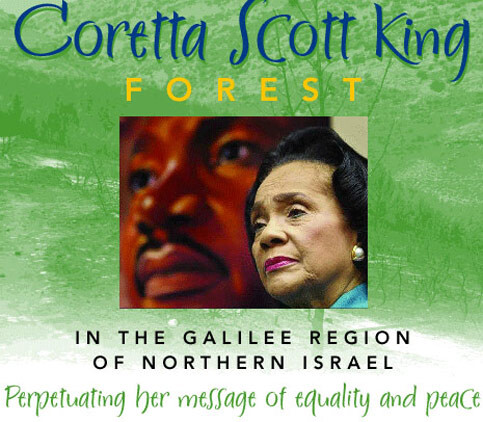

Towards the end of April, the Associated Press filed a story reproduced by, amongst others, Ha’aretz, Guardian Unlimited, and CNN, reporting that “Israel will name a forest in northern Galilee after Coretta Scott King”, part of a wider campaign to replant “thousands of trees destroyed during last year’s war with Hezbollah”. At least 10,000 trees will be designated as a “living memorial to King’s legacy of peace and justice”, according to US Israeli ambassador Sallai Meridor. Although it was a small story that merited a few paragraphs of a news agency feed, unpacking this publicity stunt can be instructive in understanding just how successful Zionist propaganda has been in tapping into US popular culture, appropriating symbols for Israel’s benefit.

The choice to name the forest after the wife of Martin Luther King resonates with Americans on three levels, each with specific propaganda value. Firstly, it suggests a shared struggle between African Americans and Jews against persecution, a historical and contemporary reality that is both true and false at the same time. The news of the new Coretta forest was accompanied by a tree planting in Washington D.C., attended by two black members of Congress; one, Rep. Alcee Hastings, commented how “Jews and blacks share a common historical bond of persecution and perseverance”. Of course, in one sense African Americans and Jews have been and are subjected to persecution by state and non-state actors. Yet there is also a level of meaning that is explicitly Zionist — that the modern state of Israel is a besieged haven for worldwide Jewry, at once the saviour and the persecuted. In a complete inversion of reality, the Israeli state is associated with the US civil rights movement in order to appropriate a symbol of the weak’s struggle against the strong: Israel the coloniser becomes Israel the ‘victim’. It is a move that Zionism has attempted before, as Joseph Massad notes in his essay collection, The Persistence of the Palestinian Question:

Naming the ‘Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel’ as the ‘Declaration of Independence’ is then to be seen as an attempt to recontextualize the new Zionist territorial entity as one established against not via colonialism.This strategy has been given a new lease of life in recent times, as many of the ‘left-liberals’ busy clipping up in their existential battle against Islamo-fascists have thus repositioned Israel as ‘anti-imperial’ to the extent that it finds itself subject to ‘jihadi terror’.

Secondly, it is also significant that the symbolic tree-planting took place at a church. Most analysis of Christian Zionist support for Israel in the US has concentrated on the typical image of white evangelical southerners, yet black-majority Protestant churches, often rooted in the Pentecostal tradition, can be more fervently Zionist. Surveys conducted by the Pew Forum have found support amongst African-Americans for views such as, ‘Israel fulfils the prophecy of the second coming’, to be higher than the average on both a national level, as well as amongst Protestants. The modern state of Israel has a lot of Western Christian friends, even those who would not subscribe to the full package of prophecies, rapture, and ‘end times’ countdowns. Raised in Sunday school, familiar with the Biblical stories of the ancient Israelites, this ‘Zionism-lite’ is more affection than theology, culture rather than textual interpretation.

The choice of King brings together both these strands. The Israeli ambassador to the US, in the officially released report of the tree-planting, said how he was “inspired by the Kings as a young child in Israel”, who “ ‘made the world a better place, and we think made all of us better human beings’ ”. The official site of the JNF announces that naming a forest after Coretta Scott King is part of “perpetuating her message of equality and peace”.

Thirdly, this publicity stunt is custom-made to chime with other aspects of US culture. You can tick the box for the favourite issue of the day, the environment. “By planting trees in Israel”, the JNF reminds us, “you have helped curb global warming”. The Israeli embassy goes one step further, suggesting Israel’s entire history as a state has been to the environmental advantage of mankind: “Israel’s forestation efforts help the entire region. Far from greening Israel alone, the hundreds of millions of trees planted in Israel over the past century have provided environmental benefits that know no borders”.

More powerfully than this rather forced pitch, however, is the extent to which the JNF’s work in forestation and other ways of “preserving and developing the land of Israel” strikes a chord with the US’ mythologized history of the frontier and the Wild West. On their website, the JNF proudly state that their “singular task” has been the “reclaiming of the Land of Israel” (my emphasis). Reclaiming, of course, implies two things: that the land was possessed by an Other, and that this possession was illegitimate. Zionists continue to take advantage of the US’ own past expansions at the cost of an indigenous population. See, for example, the official blurb at the end of the organisation’s press releases, which describes the JNF as “supporting Israel’s newest generation of pioneers in developing the Negev Desert, Israel’s last frontier”.

The Negev is a useful link for an examination of why such comprehensive and thorough propaganda is required; the smoke screening of Israeli apartheid, and specifically, the role of the JNF in its implementation. Less than a fortnight after the Coretta forest announcement, an illustration of the real nature of the policies the JNF are involved in implementing was reported in the Israeli press. Ha’aretz published a story on 8 May relating the demolition of a Bedouin village in the Negev that left 100 people homeless, an all too common event. With almost unbelievable irony, the Israel Lands Authority (ILA) described the event as the evacuation of “invaders”. Welcome to life on Israel’s “new frontier”, where as no sooner are the villages destroyed and the Arabs cleansed, then the JNF is ready to move in to make the desert bloom.

Thus despite the JNF’s public image, the organisation has played a key role in Israel’s appropriation of land belonging to Palestinians, both in the major expulsions of 1948, as well as the piecemeal ethnic cleansing that has continued ever since. The official line hints at the truth: the organisation self-defines its modus operandi as being “to serve as caretaker of the land of Israel, on behalf of its owners — Jewish people everywhere”. Thus the Middle East’s ‘only democracy’ is not, in fact, a state for all its citizens (i.e. native Palestinians), but is ‘owned’ by Jews worldwide, a claim contested by both Jews angry at the presumption, as well as the Palestinians whose land has been stolen.

On the rubble of Palestinian villages, the JNF planted forests; on the remains of village schools, picnic parks sprung up. Maps were redrawn, Arab place names erased, and soon, all that remained were piles of stones, the fragments of structures, and the memories of the exiled. Uri Avnery describes what happened in the years following Israel’s creation:

the new state transferred to the KKL millions of dunams of land expropriated from Arabs — the refugees who were not allowed to return (‘absentees’ in legal language), those who had remained in the country but were absent on a given day from their villages (‘present absentees’), as well as Arabs who became citizens of Israel.Avnery, in his piece, ‘Abolish the JNF’, notes that the JNF’s statutes “explicitly prohibit the sale or rental of land to non-Jews”, meaning that a Palestinian in Israel “whose forefathers have lived here for hundreds — or even thousands — of years, cannot acquire a house or an apartment on its land”, in contrast to a Jewish New Yorker who decides to emigrate. Uri Davis, author of Apartheid Israel, also succinctly summaries the disparity between the JNF’s public face, and the reality buried underneath the top soil:

[The JNF] projects itself as an environmentally friendly organization concerned with ecology and sustainable development. It plants forests and establishes recreation facilities open to all. Well, it is the case that JNF forests and facilities are open to all, but it is equally the case that that most — almost without exception all — of these forests are planted on the ruins of Palestinian Arab villages ethnically cleansed in the 1948-49 war.One of the JNF’s forests is Birya, planted on the ruins of ethnically cleansed Palestinian villages — and it is here that Israel will pay homage to Coretta Scott King. What better example, not only of the Palestinian Nakba, but also the extent to which Zionist propagandists will not only deny the ethnic cleansing, but even repackage colonialism as the victory of the colonised.

Ben White is a freelance journalist specialising in Palestine/Israel. His website is at www.benwhite.org.uk and he can be contacted directly at ben at benwhite.org.uk.