The Electronic Intifada 1 November 2006

Palestinians detained at an army post after breaking curfew (Breaking the Silence)

Standing at 6’1, with strong build, a full beard, and long dark hair, Yehuda Shaul seems like an unassuming young man.

Wearing dark cargo pants, and a long-sleeved blue shirt, he paces back and forth taking in the whole room. It’s hard to notice at first but his blue velvet kippa (skull cap) rests easily on his head.

His voice is mellow and calm. He has a disarming smile that lights up his entire face when he’s happy and talking about the things he loves (one of which is football). But behind the smiles and the passion for the world’s most popular sport is a young man who has seen and done things no young person should ever have to endure.

A soldier is born

He was born in Jerusalem, the son of an American born father and Canadian-born mother who immigrated to Israel in 1973, the year of the Yom Kippur War. The 24 year old, much like every other male in Israel, was drafted into the army at the age of 18. Everyone is obliged by law to serve in the military; men serve for three years and women for two.

Shaul wanted to serve in the Israel Defense Force (IDF) not because he was required, but rather that he wanted to. “I went because to me, it was obvious since I was five or six that I was going to be a soldier, that when my time comes at the age of 18, I will join the army … The only question was, will I join the regular army or be an elite commander in the army,” he says.

During a very powerful and emotional ceremony at the Western Wall, Shaul swore an loyalty oath with his fellow soldiers, promising to protect Israel.

But towards the end of his time in the army, Shaul remembers something that began to change his view about the IDF and Israel’s defense against terrorism.

He explains, “Somewhere towards three months at the end of my time in the army, I began to think about my life as a civilian. Trying for the first time after two years and ten months of living military life … trying for the first time to ask myself who is Yehuda? Who am I what do I want to become? And for me that moment was a very terrifying moment. It was a moment to stop thinking about being as a professional combat soldier and start thinking like a civilian. Stop thinking from inside and start observing from outside what’s going on.

“It’s a very terrifying moment because, in one second the military terminology and the way of thinking doesn’t apply to you anymore and in one second you lose the justification for 95 percent of actions you took part in the past two years and ten months.

“And when I felt that, I felt that something mad was going on around me. I felt I can’t continue my life without doing something. I didn’t really know what it meant, what I was going to do; but I started talking to some of my comrades and I discovered that we all felt the same. We all felt that something wrong was going on around us.

“We started talking about what we’ve done and that’s how Breaking the Silence got started.”

Speaking Out

Breaking the Silence (BTS) is a group of discharged soldiers who are veterans of the second Intifada, which began in September 2000. The group has tasked itself to reveal to the Israeli public the daily routine of life in the territories, a routine that gets no coverage in the media.

For Shaul and his comrades it was obvious that they were going to do something, and it was obvious that it was going to be about Hebron. Hebron is a Palestinian city in the West Bank located to the south of Jerusalem. It is considered a holy city to Jews, Muslims and Christians. This is where Abraham, Isaac, Sarah, and Jacob are buried in what is referred to by the Jews as The Tomb of The Patriarchs, and by the Muslims as al-Haram Ibrahimiyah. Furthermore, Abraham is an important figure in all three religions.

Out of the three years that he served in the occupied territories, 14 months were spent in Hebron. In March of 2004 Shaul was discharged. In June 2004 he and some comrades started BTS with a photo exhibition about Hebron.

The name Breaking the Silence was apt because what is going in the occupied territories is one of the biggest taboos in Israel. “It’s like the thing you never talk about,” says Shaul. “It’s the dirt from the backyard that you do everything to keep in the backyard. The last thing you want is that this dirt will come to the front.”

The title of the exhibit was Bringing Hebron to Tel Aviv. Shaul explains that if anything symbolizes Israel, it’s Tel Aviv. In Israel, Tel Aviv is often called “The Bubble.” It is a place where people would rather sit down in coffee shops and not see anything more than a few feet around them.

When the exhibition opened, it was a huge success. Over 7,000 visitors attended the exhibition. Shaul and his fellow soldiers were shocked by the attendance. For several days, the Israeli media reprinted many of the soldiers’ testimonies from Hebron.

The act of the exhibit was a very personal one. None of them were really sure why they were doing it at the time, only that they felt they had to. But something remarkable happened during the exhibition. Out of the 7,000 that came to see the works, some had also been recently discharged from different units serving in the occupied territories. While Shaul and his comrades stood by different works, the soldiers that came to see the works walked up to many of them and said; “this picture you have on the wall, I have the same from Nablus.”

Shaul realized from these soldiers who served in various parts of the West Bank and Gaza that the story of his battalion was not unique, but rather the story of all his generation. It was then that those who had put on the exhibit had to continue their work. They began to videotape and audiotape the testimonies of soldiers who served in the occupied territories. As of now, BTS has interviewed over 400 people who served as conscript soldiers.

The goal of BTS was not just to show shocking pictures. Not to tell horror stories about life in The West Bank or Gaza. The goal of BTS was to help people understand the mindset of occupation, to understand the mindset of an occupier.

Car keys confiscated from Palestinians by Israeli soldiers are part of the exhibition (Breaking the Silence)

Games Children Play

Shaul explains that when one is in the occupied territories, things might seem exciting at first but over time the soldiers tend to get bored; they become numb to the situation around them. “Eight hours on, eight hours off, you start to get bored so you begin to make things a game,” he says. “You start to aim your rifle at kids and see them through the scope of your rifle and take a picture. Then you aim at your friends and take a picture. The rifle is no longer a killing machine; the rifle becomes a part of your game, the way to pass time.”

Often, these games would extend to the Palestinians who would have to go through checkpoints.

“We use to say that there are two kinds of blindfolded and handcuffed Palestinians. The first kind is called wanted terrorists. These are the people that you get the ID numbers from the [security service], [and their] address, you come in the middle of the night into the house, catch the guy, bring him back to the barracks, blindfolded until he is taken away.

“But the other kind, what we call in Hebrew “Dry outs” or more professionally, detainees; these are the Palestinians who broke curfew … During 2002 through 2003 there were more than 500 days of curfew in Hebron. And we would lift it every few days so people could get food for maybe two or three hours. But if someone were to leave after these hours to get food for his family, then he would be detained for five, six, or seven hours. You must educate them.

“Or if you ask the Palestinians to stand in one nice line and one guy at the end starts to scream, that could be seven hours, ten hours.

“If you call on a Palestinian to show his ID and he smiles too much, then that could be two hours or it could be eight hours. It just depends on which side of the bed you woke up on that morning.”

Over time, Shaul says that the Palestinians stop being people and simply become objects.

The Wrecking Crew

Shaul explains that at the beginning of the second intifada, when the IDF would occupy a Palestinian home, commanders would given explicit instructions. The only things allowed to be used from private property were things for military purposes.

If they would occupy the house for more than a few days they might throw out the family, or remand them to the first floor or a basement. If a chair or a table was needed to build a post, a soldier was allowed to use them. “Believe it or not, the first houses we entered, before we left, we washed the floors,” Shaul recalls. “This is what we called an enlightened occupation.”

Eventually, the units would get more and more comfortable in the houses, and over a period of time the soldiers would become bored and they would start to break things.

Once, when Shaul’s battalion was doing an operation in city of Ramallah, a World Cup match was underway. “We looked around and found a house, entered it, kicked the family out, watched the game, and when it was over we left and went back to our mission,” he says.

During Operation Defensive Shield in 2002 in the town of Jenin, Israeli bulldozers, made by Caterpillar, rumbled through the narrow streets, taking the walls of houses and shops along the with them.

“After a week the soldiers in Jenin ran out of water,” Shaul explains, “So the commander gets on the radio and tells his men to go to a shop to get more water. We need water, this is a military need, right? So the soldiers go to the store in an armored personnel carrier (APC) and get water. Well, a week with out water is also a week without cigarettes, so they take cigarettes, and a week without cigarettes is probably a week without chocolate, so they take the chocolate as well.”

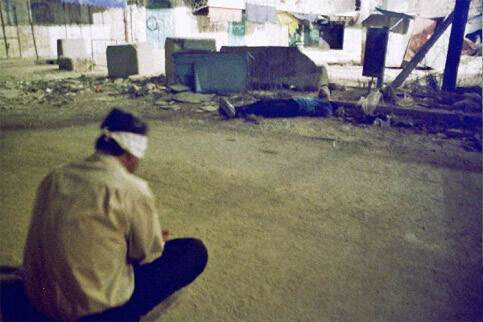

Palestinians detained in a street near an Israeli army post (Breaking the Silence)

The Blender

Yehuda Shaul’s professional infantry training was as a grenade machinegun operator. During the second intifada, his first assignment in Hebron was to stand post at a school over looking a Palestinian neighborhood called Abu Seniehi.

Every night at approximately 6pm, Shaul says, Palestinian militants would shoot at the settlements in Hebron, and the IDF would return the fire.

Shaul’s platoon sergeant informed him that every night they would hear gunfire and that he had to react and return the fire. It is important to note that a grenade machinegun is not an accurate weapon and that the targets that are firing at, within a dense urban area, are almost impossible to spot.

When Shaul realized what he was going to have to do he became very nervous. He worried for hours about what would happen when 6pm rolled around. “At 6pm the shooting starts and you get your orders over the radio. You approach the machinegun. You still know that something is wrong, that something is not right. You don’t believe that you’re going to shoot the neighborhood … for what are we here?

“So you pull the trigger you spray the area you pray that the less amount has been fired and then there is four or five seconds of tense quiet. You pray you haven’t hit innocent people. But the next day you’re less tense, the third day, and then after a week it becomes the most exciting moment of the day.

“After awhile you see that the Palestinians are not getting the message. They are continuing to shoot. So, maybe we shoot at 5:30pm to deter them. Then over a little bit more time we go out on patrols and we see a car and we decided to explode it to send out a message. Now when I talk about this I am talking about how the mission starts and where it goes. How it just becomes a part of you. The blending.”

Where do we go from here?

BTS identifies two levels of silence. The first level is the silence of the combat soldier who doesn’t understand what’s going on. The second level of silence is that which is conveyed to the Israeli public regarding what is really happening in the occupied territories — what is happening to their sons and daughters, husbands and wives.

Yehuda Shaul stares on intensely and leans forward. “No one wants to hear what’s really going on in the occupied territories. No one wants the dirt from the backyard to get to the front. It’s time to put the dirt so that everyone can see and that we can all begin to address it”

Related Links

Christopher Brown is an independent grassroots journalist living in San Francisco, CA. he spent three years living and working in the Old City of Hebron from 2002 through 2004 and interacted often with Yehuda Shaul’s battalion while they were stationed there.