The Electronic Intifada 6 February 2006

Like hundreds of Palestinian towns and villages, Lifta was forcibly depopulated and ethnically cleansed in 1948.

In Israel, renovation projects are frequently used in order to build a national narrative, ignoring the deep contradictions between planning and human rights that inevitable become apparent in such initiatives. Lifta, like the ‘unrecognised village’ of Ein Hud, is a potent symbol of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict and its tragic human consequences. The ‘unofficial’ Palestinian village of Ein Hud was built by refugees fleeing the original Ein Hud nearby; Israeli artists later colonized the old village, renaming it Ein Hod. The new Ein Hud’s struggle for legitimacy (and the planning system’s refusal to grant this) was the subject of FAST’s recent architecture competition.

The village of Lifta, which lies just outside Jerusalem, has been abandoned since the Israeli army drove out the last of its Palestinian inhabitants in 1948. Today Lifta is more or less a ghost town while the former villagers live mainly in East Jerusalem and Ramallah. Now, however, a renovation project aims to turn Lifta into an expensive and exclusive Jewish residential area - reinventing its history in the process. While Ein Hud and Lifta are historically and spatially unique, they are both symbols of the deep complexity of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that began not with the occupation of 1967, but with the creation of Israel in 1948. Viewing the history and transformation of each, from Palestinian village to the realization of a utopian ideology of a modern society and nation, reveals much about the conflict, and how planning tools are fundamental in making the transition.

One nation - Israel - is being invented through national narratives and ethos, through culture, language, image, history and space, another nation - Palestine - is being brutally negated. It is essential to study this transformation process, from land confiscation to the displacement of one group and accommodation of another, the role of master planning, zoning, programming, planting, demolishing, fencing, and so on. Only in becoming fully aware of this process can we actively realign our profession to create viable alternatives. As with Ein Hud, we aim to explore the possibilities for an alternative planning solution, for Lifta.

The renovation of Lifta should take into consideration not just the esthetic history of the village but also its human component. In contrast with Ein Hud, in Lifta we have the opportunity to offer an alternative before a new order has been imposed, making it subsequently harder to achieve an equal solution. The alternative to Lifta’s official renovation plans will therefore be the result of activism and planning.

“Heritage is our legacy from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to future generations. Our cultural and natural heritage are both irreplaceable sources of life and inspiration.” - UNESCO

The masterplan: The Lifta legacy

In its present derelict, largely abandoned state, Lifta captures the moment of destruction of Palestinian life in 1948, when Israeli forces conquered it. Lifta’s 2,000 villagers fled - mostly to East Jerusalem and the Ramallah area. However, unlike many of the 530 Palestinian villages and towns also conquered and usually bulldozed during the war, many of Lifta’s 450 houses remained untouched; yet the village was never ‘officially’ resettled. Unlike Ein Hud (which later became Ein Hod), Jewish settlers did not inhabit Lifta. This does not mean that all the original houses remained vacant. Several Jewish families did move (illegally) into former Palestinian homes. Some of these families have been living there for a number of decades, and seem to have become permanent residents.

In another part of the village, people from the fringes of society have settled: drug addicts and dealers, run-away teenagers, as well as nature freaks. Even so, several dozen houses, some now falling apart, have remained empty. They stand as monuments marking the events that took place here during the 1948 War. Over the years, Lifta has remained a different and unique place, for several reasons. Geographically, it is part of the ‘new’ West Jerusalem; however, it represents and symbolizes the architecture and the topography of Palestinian towns. Lifta remained in its place, as if frozen in time.

Topographically, it is located lower than its surroundings; this gives the feeling that Lifta somehow exists beneath the surface of the city. It seems to occupy a different level of history, geography and society. Those who have inhabited Lifta since 1948 are the ‘other,’ in the context of the larger Israeli public. They live outside the borders of law and order, and even outside our vision, since they usually go about their shady business down below, near the village’s fountain. As mentioned already, Lifta is unique in that, unlike many other villages, its houses remained almost intact, yet without being inhabited by Jews as part of the Zionist enterprise.

Many of Lifta’s refugees live today in East Jerusalem, not far from their village. This is not unique to Lifta, as refugees often live in close proximity to their pre-1948 towns and villages.2 However, Lifta is distinctive in that many of its original inhabitants are not citizens of Israel, but rather East Jerusalem residents, who have limited civil status. ow, a new development plan intends to turn Lifta into exclusive real estate. The plan would transform the village into an expensive living area, with some shops, a hotel and open green areas, while at the same time maintaining its villagey atmosphere and keeping some of its original buildings and structures. The plan was submitted to the Jerusalem Municipality Planning Committee in 2004 and was approved by a regional committee. Reading this plan, together with an earlier development plan from the 1980s, consistent attitudes are revealed in plans for reshaping abandoned Palestinian villages.

It is of great significance that the plan does not ignore the many remains of the Palestinian village; on the contrary, these are deconstructed and become a central element of the new design, with dozens of them earmarked for preservation.

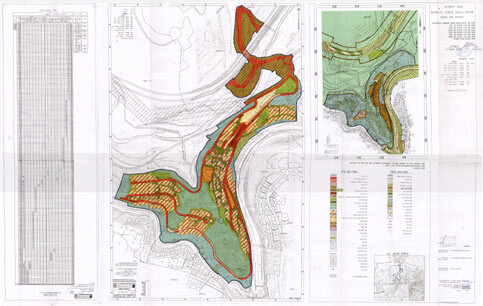

The official Israeli masterplan of Lifta.

In addition, the natural scenery of the place - the spring, trees, and terraces - are a major component of the plan, which strives to preserve the authentic surroundings of Lifta. Israeli authorities took part in creating the plan, and also gave it an official approval, and for this reason it is informative to observe the connection between state ideology and planning. Lifta has been partially in ruins since it was conquered in 1948. The lands belonging to it were confiscated by the state. However, the centre of the village was never rebuilt.

Today, there are some 55 Palestinian houses remaining from the original 450, some standing intact while others are almost entirely derelict. Several houses - those closest to the road leading to Jerusalem - were occupied decades ago, by Jewish families who still live there. These families apparently will not be evacuated when the new construction plan is implemented. The plan essentially focuses on reshaping the space of Lifta’s village centre, the surroundings of the famous spring, and the bottom part of the wadi, the ravine on whose slopes Lifta is situated.

The plan, numbered 6036, was designed by two architect offices: G. Kartas - S. Grueg and S. Ahronson, and is part of the “local space planning of Jerusalem.” The plan was submitted on June 28, 2004, and according to its title refers to “The Spring of Naftoach (Lifta).” The plan includes a change to the previous construction plans for the area.

Desirable relicts

The plan’s goal, as stated in the document, is to build residential areas, some of them preserving the original houses that still exist in the village centre. It includes plans to build areas for commerce, shops, public buildings, a hotel, and passages. In addition, some part of the scenery will remain untouched for the public to enjoy. The total area to be included in the plan is 455 dunams (45,000 square metres). Some 50 houses located before 1948 in the centre of the Palestinian village will be preserved. A total of 243 housing units will be built, as well as a 120-room hotel.3

The relations between the masterplan and the Palestinian village of Lifta are various; in the plan’s goals it specifies: “instructions on how to preserve, restore and reconstruct the existing structures and the terraces inside the village of Lifta, and their integration with the new developments in the area.” In the chapter about “A particular residential area to be preserved,” these references can be found: “any additional building or reconstruction or renovation of houses in these areas will be conducted by maintaining the architectural nature of the existing structures that are destined to be preserved, including their building scale and architectural details, and by keeping and completing the distinctive fabric of that area.”; and “there will be no changes in the level of the lands and the terraces; no damage will be caused to trees, apart from when paving access routes and shops; while “the construction work of preserving, restoring and expanding will only be done reusing old stones”.

On “areas for institutions,” the plan states that “construction will be carried out using natural square stones chiselled manually. Building with stone that has not been chiselled is forbidden. On the terraces, it says: “All the existing terraces … are to be preserved and restored … Terraces that are to be restored will be created using stones similar to the existing ones” On detailing “conditions for building permits”, the plan says that it will be required to hand in “a document that includes detailed instructions … for preventing destruction of structures for preservation, careful detailing of the greenery in the area, and explaining the methods of construction to be used so that the existing vulnerable fabric is not harmed”.

On the trees in the area, it says: “Those trees that are located in the areas of buildings, roads and infrastructures are meant to be preserved and uprooting them is forbidden”. On the “particular residential area for preservation,” a previous construction programme for Lifta is mentioned. Dating back to April 11, 1984, plan number 2351 is still to be implemented as part of the new plan, excluding specific articles that contradict the newer plan. Plan 2351 was never realized, but looking at its instructions regarding the preservation of Lifta’s remains is important for our topic.

The goals of the previous plan were that inside the village area there would be “museums, shows, offices, and institutions that care for nature, landscape and that place.” It included “instructions for preserving the village, the orchard and the spring”; It insisted that, “the area designated to be preserved and renovated shall remain open to the public. Usages in that area that would involve closing it off to the general public will not be approved. Fencing the area selected to be restored is also forbidden.”

In addition, “in the area of the nature reserve, it will be allowed to conduct actions needed for preserving the nature and landscape of the spring and its immediate surroundings, the agricultural steps and the orchard; it will also be permissible to renovate the existing structures in the area of the nature reserve - these building can be used only as museums and study rooms”. On “buildings to be preserved,” the plan mentions three olive oil process structures and two halls dating back to the time of the Crusades. This are to be renovated, and “any archaeological findings there are not be harmed”.

Places without people A ccording to this view, the remains of Lifta exist in the landscape and should be preserved. The trees, spring, terraces, natural stone, remaining houses (complete and incomplete), and the olive oil process structures are all originally from Lifta. They even have character, like “distinctive texture” and a unique “architectural nature.” The plans are thus not in denial concerning the Palestinian space of the village. On the contrary, they are aware of its advantages and use them, through the practices of preservation, to elevate the touristic and commercial real-estate value of the project. This comes across clearly in the earlier master plan (plan 2351), which stresses that “the area which is subject to directives of preservation and renovation is to remain open to the public.”

Those who will visit the place, and not Lifta’s residents alone, will be able to enjoy the remains of the renovated village, and access to it will not be denied in any way. The aesthetics and the architecture of the Palestinian ruins raise the value of this space, and therefore will be professionally safeguarded.

[NEXT]