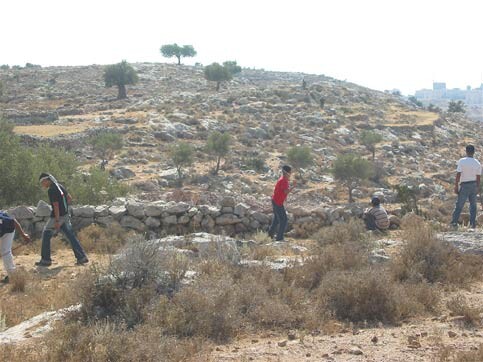

Birzeit 17 July 2005

Bil’in’s future? A completed section of the Annexation Wall. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

Long ago, I gave up wondering how Khader knows everything. When we first met, I was arriving late for an appointment at his restaurant, Seasons, which is, for anyone who has read Robert Fisk’s Pity the Nation, the Commodore Hotel of Birzeit. I recall him standing in the doorway, arms folded, head cocked to one side, “Hello Zaki, you have time to catch your breath, she’s in the bathroom. You take your coffee with one sugar, right?” Right. Have we met?

So last Friday morning, as I sat at Seasons with seven international students preparing to embark for the Wall demonstration at Bil’in village, there was no better company than the avuncular restaurateur with an uncanny resemblance to Marlon Brando (circa Godfather I). “You know, there is a shop on the way to where the soldiers will be,” Khader said as he brought us complimentary watermelon slices, “You should buy some onions there.”

The idea that, when tear gassed, shoving raw onion wedges up one’s nose might be desirable, even pleasant, had not yet settled. But at this point, Khader could have talked about hippopotamus birth defects and that too would be welcome. We were nervous. Although our respective demonstration experiences ranged from G8 summits in Europe to anti-eviction sit-ins in Soweto, none of us — not even the Irish guy — had taken a hardy dose of tear gas, much less rubber/metal bullets. Based on what we knew, we would at least experience the former.

The weekly demonstrations in Bil’in, where the path of Israel’s illegal Annexation Wall cuts through part of the village and destroys several olive farms, have been one of the longest-standing and most underreported acts of peaceful resistance of our era. (Although much of the Wall has been completed, the section going through Bil’in consists of 30-meter wide razed pathway that scars the countryside.) Since February this year, the campaign has held 51 demonstrations, which involve local and international contingents that have numbered as high as 500.

The demonstration itself has developed an almost ritualistic pattern that’s very typical of peaceful protests in Occupied Palestine, where Israeli soldiers tolerate passive resistance for so long before they fire tear gas or rubber-coated bullets — which break the skin and often kill — into the crowd. Doing this invokes stone throwing from local youths, who weather a day-to-day narrative of harassment, beatings and arrests, quite apart from what the internationals experience. If one believes in the adage that “the powerless don’t choose violence, violence chooses them,” then it could be applied here.

One by one, protestors were arrested. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

The final arrest. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

To label Israelis the provocateurs of these affairs doesn’t require conjecture. In June, Israeli Colonel Yoni Gadji confirmed to Israel’s Haar’etz newspaper that undercover military personnel mingled with the demonstrators and threw stones at Israeli soldiers, thus opening the way to violent conflict. The Israelis also bring cameramen to capture the incriminating acts of these stone throwers so that they can justify the use of bullets — which graduate from rubber to metal — thus making a grotesque comedy of presumed innocence.

Given the attention span of the international media, why shouldn’t they? Within a week of the same Haar’etz report, Josef Federman of the Associated Press filed a story titled, “Israel Uses Sound Technology on Rioters.” Rioters. It was not until the last line of Mr. Federman’s report, which centered on the progress of the “425-mile barrier,” and how “the [sound] weapon uses special frequencies to disperse the crowd,” that he wrote, “the demonstration organizers had decided to hold a nonviolent protest.” That Israeli agents went undercover remained an allegation by “Palestinians and left-wing activists.”

Admittedly, my reasons for joining last Friday’s rally were not entirely clear, which bothered me as our taxi van clung to the sharp embankments west of Ramallah. That, and the sudden realization that I had forgotten my passport, led me to break the silence by speaking with Ben, a jovial physicist from London. When the sound grenades go off, do you think you’ll run? I asked him. “As fast as my little legs can carry me,” he laughed. We made a half-hearted pledge to keep our cool and not abandon one another should such an event arise. After a moment’s silence, he turned to me with sincerity and said, “I do feel like we’re doing our bit.” I couldn’t bring myself to tell him that I didn’t share his idealism.

The road to Bil’in passes through several remote villages whose subsistence depends largely on olive farming. But no one has to tell you when you’ve reached Bil’in. The streets are lined with Palestinian flags and posters of martyrs from the village – mostly young boys who fell to “rubber” bullets. Shortly after we arrived, we were directed to a house where the International Solidarity Movement (ISM) convenes. Along the way, we met a handful of young Israelis who had refused or avoided military conscription to take up the anti-segregation cause. One explained that it wasn’t terribly difficult to employ the I-might-commit-suicide excuse to avoid service, since self-inflicted deaths have taken more Israeli soldiers than clashes under the Intifada.

Inside the ISM house, local Palestinian leaders briefed the variegated internationals on the demonstration’s agenda, which would involve marching on the Israeli barricade in rows of ten with arms locked. The march would not end until the lines reached the path of the Annexation Wall, which stood on a hill about a kilometer away from the expected Israeli line. Outside, activists pieced together a steel and wire-mesh yoke that the front ten demonstrators would wear over their soldiers. Meanwhile, Israeli and foreign documentary makers tested their equipment or interviewed local organizers. One of my Birzeit colleagues made an onion run.

Israeli soldiers break up the sit-in. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

They were there. They were ready. This time, according to a nearby veteran (a middle-aged Jewish man from Pennsylvania), their barbwire coils were even closer to the village than they had been the previous week. Behind the barrier stood several dozen soldiers with tear-gas canons, sniper rifles, riot shields and clubs. To their left were another dozen-odd armed personnel with video cameras. It is rumored that the cameras are used to compile a black-list database for Ben Gurion Airport officers, but the immediate effect was telling, as many of the Bil’in villagers in our ranks fell back into olive groves or behind walls: When the day is done, it is they who live a mile from Israeli soldiers.

Later that day, I would be sitting at Seasons, sharing a beer with a friend who is a political science professor from New York. We would discuss the events of the day, then return to our summer apartments without worrying about Israeli commandos kicking in our doors that night. We would note with academic detachment how the different factions – ISMers, progressive Jews, foreign students, Palestinians – carried respective political currencies that would play off one another for better and worse, in a fashion not unlike medieval warfare, where the archers, infantry and cavalry played complimentary roles.

Frustrations mount on the front line. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

Regardless of these criticisms, it was impossible not to be impressed with the first wave that confronted the Israeli barricade. The steel-yoked front line made a mockery of the barbwire by moving laterally, forward, and eventually around it. The Israeli soldiers, burdened with layers of armor and US military hardware, became visibly frustrated. Some drew batons and pushed the demonstrators warningly. I could only wonder if the presence of Jews, who sang Hebrew peace songs, prevented a quicker, more violent conclusion. But such a conclusion was inevitable.

It took a stone. Not one that was thrown, but one that happened to trip a woman in the front. Somehow her fall set off a domino reaction that began with a sound grenade, followed by tear gas, or what we later realized were sound grenades that exploded into tear gas. Ben, who stood several meters back to take photos, recalled a hissing sound that zipped over his head. He then noticed dark metal objects resembling soft-drink cans falling around him. No sooner did he begin to wonder “why they were throwing Coke cans at us,” than the objects exploded, one by one, each sending reverberations that literally rattled our innards.

Thinking that the demonstration would disperse, I ran away from the front and joined Ben by a fence post. “Quick mate, give a hand, I have to reload my camera,” he shouted. As I bent over with my back to the Israelis, holding Ben’s film, a hissing projectile raced from behind and terminated with a wild pain that shot up my backside. BOOM.

Four soldiers invading Bil’in. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

From there, I could see that the demonstration front line had remained in tact. Many of the soldiers had begun what they were perhaps waiting to do, which was to invade the village in search of Palestinians. The division of ranks was clear now.

To their credit, about two-dozen Palestinians, internationals and dissident Israelis had commenced a passive resistance sit-in on the Israeli side of the barbwire. One of them, I noticed was my friend Salma,* a Palestinian American, who sat on the fringe of the cluster. Feeling guilty about Ben (wherever he was), I ran to Salma, sat down and locked arms with her. “You sure you want to join the fun?” she asked smiling. Sweat streaked down her face, and I imagined that she felt as hysterically dazed as I did.

The passive resistance sit-in. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

Amidst all of this, Salma, who remained incredibly calm, looked up at one of the soldiers. “Isn’t it funny how we look just alike?” she said to him. He glanced down then quickly looked away. She continued: “I mean, your nose is big like mine. We have this darkness under our eyes. You could be my brother.”

Finally, the ranking officer stepped forward and delivered a verdict: We had the choice of being arrested or leaving peacefully, he said, like a flight attendant asking whether we preferred the fish or chicken dinner. The majority of the Jewish and Palestinian protestors decided to be arrested (everyone, with the exception of the Palestinians, were released two hours later). Salma and I mutually agreed to leave, recalling that we had an Arabic midterm exam on Monday. In reality, of course, we simply didn’t want to be arrested.

We stood and dropped back to join the rest of the onlookers behind the barbwire, as the soldiers forcefully carted the demonstrators away to an idling vehicle. The last person to be cleared was an elderly Jewish man, who remained crouched on the scorching street, arms locked with imagined colleagues.

Demonstrators are pulled away. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

Over the next hour, I witnessed the unraveling of Phase One of Friday’s demonstration. Many of the internationals retreated to the other side of Bil’in, and took refuge in sidewalk shops over cold drinks and ice cream. Several waited for taxis to return to Ramallah, or to take an afternoon trip to the Dead Sea. (As shamefully ironic as it is, given that Palestinians are forbidden access to the Dead Sea, your correspondent would have gone too had he remembered his passport.)

Meanwhile, the Israelis had taken the west side of Bil’in, using a strategy of drawing Palestinian youths – who had now employed long-range rock slings – into the center of roadways and attacking from the sides. The atmosphere erupted with piercing cracks as rubber-coated bullets sailed overhead. Seeing two soldiers coming around a corner, I ducked into the open door of a house to find two old men playing cards at a kitchen table. One of them looked up, smiled, then returned to his hand.

Bil’in youth attempt to take the hill. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

It was clear, by their ability to avert bullets and advancing soldiers, that the Palestinian youths of Bil’in were commandeering Phase Two of the demonstration: Giving the soldiers hell as they retreated westward.

Since the gunshots had faded somewhat into the distance, I set out to find my scattered Birzeit friends. Several of them were listening in on an ad hoc ISM convention that was being held under an olive tree. As the ISMers discussed the strengths and weaknesses of the day’s events, gunfire continued to crackle from beyond the demonstration site a half-mile away. Growing bored, I jogged in the direction of the sounds to see what was happening.

The barbwire was gone, and spent tear gas canisters littered the ground. I arrived at the edge of a ravine, which stood between myself and the Annexation Wall route, only to witness a scenario that was, for lack of better words, breathtaking. On the western slope, Israeli soldiers dug in behind ancient stone walls and olive trees, firing rounds at Palestinians on the eastern side; the latter still armed merely with stones. The Palestinians also had men stationed to the north and south; when the Israelis tried to flank them, these men shouted for everyone to fall back. An ambulance waited nearby.

I was approached by one of the youths who insisted on showing me how everything worked. We ran from tree to tree, making our way to the front line. “Here, behind this rock. Get down,” he said. I asked him if the Israelis were using rubber bullets. He replied with an exasperated smile. “Rassas mad’ni,” he said, metal bullets. There was no way to know for sure, so I dismissed the issue.

Bil’in youth with long-range rock sling. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

Eventually, the Israelis regrouped and walked into the setting sun. The Palestinians didn’t hesitate to pursue them over the hill, while hurling stones and igniting brushfires on the “Israeli side” of the Wall route. I followed them to the summit to find, not far from where I stood, a sterile new world of uniform condominiums, swimming pools and non-indigenous, water-hungry evergreens. Israel.

The Israeli soldiers would take one last charge at the Palestinians before sundown. For now, I was indulging in an existential victory: We had taken the hill, whatever that means.

* Fictitious name.

Zachary Wales is a masters student at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. He is also a co-founder of Labor for Palestine, and he currently takes summer courses at Birzeit University.