The Electronic Intifada 21 May 2005

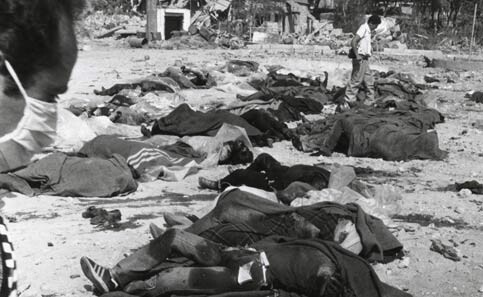

Shatila camp, Beirut, 20 September 1982 (Photo: UNRWA/Beirut)

The massacre no one wants to speak of.

Day and night, for three days in September 1982, a massacre took place in Sabra Street and Shatila refugee camp in a popular residential area of Lebanon’s capital Beirut. Even today, few people are aware of the scale and extent of the killings that took place for 43 consecutive hours some 23 years ago. Palestinians were the target of this massacre, but they were not the only victims. Arabs of other nationalities, Turks, Bangladeshis and Iranians were also killed in their homes, in the streets, or marched to Sports City where they were shot in hastily-dug death pits.

A motley crew of Lebanese Christian militias attacked doctors, nurses and patients in the Gaza and Akka Hospitals. Axes and guns with silencers were used against everybody - including women, children, babies, the unborn, the elderly and the sick - so as not to draw attention to what was taking place. In the aftermath of the slaughter, rescue workers found that acid had been poured over people’s faces and stomachs, eyes had been gauged out and bodies were booby-trapped. The French had to send in bomb-disposal experts to assist with the recovery. Not all the victims were found, and many remain missing, including an abducted British citizen who was simply known as “Uthman”. Homes were bulldozed, and bodies were placed under roads that were then repaved, or dumped in pits that were then filled over with sand.

Shatila camp, Beirut, 20 September 1982 (Photo: UNRWA/Beirut)

In September 1982, Beirut was under siege by the Israeli military. The Israeli Command Centre had an aerial view of the camps, evident from a black and white photograph reprinted in the book. The Israeli army allowed the militias into the camps, fired flares in the air to light up the night, and shelled the area extensively, forcing families to seek refuge in bomb shelters where most of the killings took place. Although the book includes accounts of Israeli soldiers shepherding Palestinians to safety, these were isolated incidents. In most cases, Israeli soldiers looked the other way. The Israeli Prime Minister at the time, Menachem Begin, was quoted as saying, “Goyim (non-Jews) are killing Goyim. Are we supposed to be hanged for that?”

This 462-page book is a testimony to the victims of Sabra and Shatila. Bayan al-Hout, Professor of Law and Political Science at the Lebanese University, began writing and researching the book in the immediate aftermaths of the massacre, but did not complete it until 2003 when it was first published in Arabic. Through the individual stories of the survivors, collected during an oral history project in Beirut in November 1982, al-Hout chronologically recreates the atmosphere in the camps during the killings, rapes and abductions. Accompanied by maps and statistics, it is the most comprehensive and authoritative account of what took place in Sabra and Shatila in September 1982. As in any bloodbath, the stories are gruesome - as are the photographs, and there are plenty in this book.

Acid had been poured over people’s faces and stomachs. (Photo: UNRWA/Beirut)

In her conclusion entitled “Who was responsible?”, al-Hout analyses the responsibilities of Lebanon and Israel for their roles in the killings, highlighting the flaws inherent in the Kahan (Israeli) and Jermanos (Lebanese) reports, by referring to an international criminal law study by Francis B. Lamb, and to the MacBride Commission of Enquiry into reported violations of international law by Israel during its invasion of Lebanon in 1982. In the Appendix, she lists all the names, ages and nationalities of those killed or missing. In her introductory notes, al-Hout poignantly reminds us that the lives of those who survived Sabra and Shatila “are, in every case, influenced, modified or developed in ways they do not wish, as painful memories pull them back, consciously or unconsciously, to their tragic experience”.

In 1983 the Kahan Commission of Inquiry into the Events at the Refugee Camps in Beirut established by Israel to investigate the events, found Ariel Sharon, who was Israel’s Defense Minister at the time, “unfit for public office”. To date, no one has been prosecuted for the crimes that took place. An attempt to indict Sharon, Israel’s current Prime Minister, for “war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide” in a Belgian Court failed when Belgium’s Parliament was forced to change its anti-atrocity laws. Those laws allowed anyone to bring war crimes charges in its Courts under the doctrine of universal jurisdiction. In June 2003, US Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfield threatened to withhold financing for a new $350 million NATO headquarters in Brussels if Belgium did not rescind the law entirely. Belgium capitulated on 4 August 2003 when it changed the law.

Interview with Author

The cover of the “Shatila camp, Beirut, 20 September 1982”

Al-Hout: Sabra and Shatila was not just a massacre that happened by accident, or during the midst of the civil wars in Lebanon. It could be forgotten, after all those years, as with many of the other mass killings and assassinations that were forgotten, due to the tide of “forgiveness” that prevailed during the last 15 years (since the Ta’ef Agreement). Those who had ordered this massacre - Sabra and Shatila - were planning to “free” Lebanon from all the Palestinian refugee camps. They thought that after such a massacre, the refugees would flee, or leave, or go to hell…

However, this “much hatred” of today, as you have described it, has more than one reason. I will stop at the “famous” one, and that is the Lebanese refusal of any sort of naturalisation that might lead at the very end to issuing Lebanese IDs to the Palestinians, irrespective of the simple fact that Palestinians themselves do not want that; only when the “Law of Return” is implemented, and when the so-called Palestinian State becomes a real free Palestinian State, the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and in all parts of the world will be looked upon as real human beings.

Kattan: Immediately after the massacre happened, you began work on interviews and on documentation. Why did it take you so long to write the book?

Al-Hout: I finished the documentation period in the midst of 1985, and I mean here by documentation three different issues: the interviews with the survivors and others; collecting all available documents; the field study inside the camps that could not be done before the spring of 1984, for security reasons. Now, why I did not start writing after all this was done, is a very natural question, but we have to go back to the midst of the 80s, when there was no freedom in Lebanon, when the mere word of “the massacre” or “Sabra and Shatila” could lead to imprisonment.

At the time, I could not believe that all documents I was looking for were at last complete, and I needed a break, but not to forget. Even if the manuscript had been ready, there was no way it could have been published in Lebanon during those years. Although I was continuing with my teaching career at the Lebanese University, I did not write a single essay during those years of documentation on Sabra and Shatila. But I never stopped looking for articles, books, videos, or any sort of material on the massacre until the 20th century was about to end. I have no specific answer as to why I did not stop at any year to start writing the book. But I can truly say that in 1998, I took the decision to write the book after a severe car accident that nearly killed me. Fortunately I remained alive. I was under the impression that God spared my life to finish this book, so I started the second and last phase….

Kattan: Would it ever be possible to take legal action against the perpetrators of the massacres in Lebanon itself? If not, why not?

Al-Hout: No, but the question is, why not? Over the 17 years of civil war in Lebanon, which many refer to as the “wars of the others on our land”, there were so many killings, kidnappings and assassinations. These were done by Lebanese against Lebanese, but according to the Ta’ef Agreement, everything that occurred before 1989 ought not to be considered as crimes any more, so God forgives, or as it says in Arabic: “ ‘afa allaahu ammaa madaa”.

Kattan: Do you think an atrocity like Sabra and Shatila could ever happen in Lebanon again; and has anyone ever publicly expressed regret for what they did?

Al-Hout: Lebanon is an unpredictable state, especially towards Palestinians. I wish with all my heart that such a massacre will not happen again, but God only knows. No one has announced or expressed any sort of regret for what took place, with the exception of a very few Phalangist leaders who announced a sort of apology for all the Phalange violent activities in general, but not specifically for Sabra and Shatila.

Kattan: How have the Lebanese media handled Sabra and Shatila? Is it discussed much, or is it ignored? Are people afraid to talk about it?

Al-Hout: At the very beginning, the Lebanese media was 100% against all what happened. Journalists and photographers did their job perfectly well, but as soon as the foreign media left Beirut, almost 15 days after the massacre, no one dared to publish anything. Lebanon was then under a severe regime, and those who committed the massacre became the real rulers of the country. No wonder people were afraid to talk about it many years later. Only courageous writers used to remember Sabra and Shatila, especially the novelist Elias Khoury. However, the real change did not start until a few years ago, five or six years ago, and again it was foreigners who started talking about Sabra and Shatila, especially the Italians.

Kattan: Has there ever been a discussion in Lebanon as whether to have a “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” over the civil war, as there was in South Africa, and in other countries where major violations of human rights took place?

Al-Hout: Not at all.

Kattan: Are there any plans to create a Sabra and Shatila Memorial Day, like that for Deir Yassin?

Al-Hout: There is no official Memorial Day up until now, but there are those friends who come from abroad every September to remember Sabra and Shatila. The movement started five years ago, and as I mentioned before, the Italians started it, so a big delegation of dozens of Italian writers, deputies, politicians, artists etc come every September to celebrate the event inside the camps. Stefano Ciarini is the head of the annual delegation. He made it a habit to meet with all officials, starting with the President. Two years later, other Europeans joined the Italians, mainly the Spanish and the French who usually send big delegations. There are also many individuals who come from Germany, Britain, and even the US. I remember there was a very big event two years ago. It is needless to say that there are many Lebanese who join our European friends every year.

Kattan: Have you ever thought of making a film, based on your book, on the events which took place in Sabra and Shatila?

Al-Hout: Yes, but such a decision is not the writer’s alone, it involves many others.

Bayan al-Hout is author of “Shatila camp, Beirut, 20 September 1982”, published by Pluto Press, #25/$40. To order a copy in the US contact the University of Michigan Press on 800 6212736. To order a copy in the UK phone TPS on 01264 342832. Or visit www.plutobooks.com. Victor Kattan, Director of Arab Media Watch and an occasional contributor to EI, was a Delegate at the “German-Israeli-Palestinian Trialogue” which took place in Munich and Berlin from 6-13 April 2005. You can reach him at victor@arabmediawatch.com.