The Electronic Intifada 19 March 2005

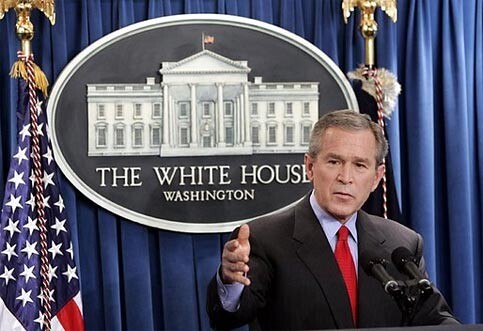

Presidents George W. Bush (White House)

Crowing over his success in breaking up the old Arab order, President George W. Bush has been strongly hinting that the first shoots of democracy pushing up through the sands of the Middle East will soon blossom into peace. Truly representative Arab leaders, we are assured, will put away the qassam and katuysha rockets and embrace their former enemies.

The model - at least in the thinking of the White House - is the peace process supposedly under way between the Israeli and Palestinian leaderships, sealed in a handshake last month at the Sinai beach resort of Sharm el-Sheikh. Mahmoud Abbas and Ariel Sharon are now doing business because both speak the same language of democracy - or so the Bush argument runs.

But neither Abbas nor Sharon paused at Sharm el-Sheikh, or have done so since, to consider how their agreements will affect the only community for which both are responsible by virtue of their office.

One and a quarter million Palestinians live as citizens of Israel, comprising a fifth of the country’s population. Sharon is their representative as head of the Israeli government, while Abbas is charged with their welfare, as he is with that of the whole Palestinian people, in his role as chairman of the PLO.

Since the official talks that came to be known as the Oslo peace process began 12 years ago, the two leaderships have severely taxed this large Palestinian community’s reservoir of goodwill. Speaking fluent Arabic and Hebrew and familiar with both cultures, these Palestinian citizens of Israel could have served as a bridgehead to peace long ago.

Instead, their potential contribution to a Middle Eastern peace process has been entirely ignored. The label most commonly adopted when referring to them, “Israeli Arabs”, is a sign of how marginalised they are from both peoples, as though neither wishes to accept responsibility for them.

The Palestinian leadership has talked over their heads, obsessively pursuing a two-state solution based on a pre-1967 division of the land that would sever the Palestinian minority’s ties to the rest of its people forever. And Israel has treated its Palestinian community as little more than temporary residents of a Jewish state, at best a demographic nuisance and at worst bargaining chips one day to be exchanged for a greater prize, such as a transfer of land from the West Bank to Israel.

The failure of both sides’ vision is exemplified in the figure of Anton Shammas, an Israeli Arab novelist whose work makes an impassioned plea for understanding through a better integration of Arab and Jewish culture. His best known novel, Arabesques, a memoir of life in the Galilee, was written in Hebrew. Today, however, Shammas lives in exile in the United States, his Israeli citizenship renounced.

Israeli Arabs like Shammas have come to understand that their identity as Palestinians has been written out of the history books since 1948, even by the Palestinian leadership. In signing up to the Oslo process, Arafat, now followed by Abbas, made a tactical decision to accept both a minimalist headcount of his population (minus the Palestinian citizens of Israel and most of the refugees) and a minimalist accounting of his future state (minus the 78 per cent of historic Palestine which is now Israel).

That would not matter for Israel’s Palestinian minority were they being embraced as fully fledged citizens of a democratic Israeli state - but they are not. Increasingly they have been tarred as traitors, as a fifth column, by Jewish compatriots raised from school age on a diet of racist stories about Arabs.

No surprise then that the Israeli police gunned down 13 unarmed Israeli Arabs and wounded hundreds more protesting in the days following the outbreak of the Intifada. Or that the Hebrew media dutifully lined up behind the police as its officers implausibly claimed that they were acting in self-defence.

After that outrage, a bout of soul-searching was required of Israeli society. The country’s politician-generals chose instead to shore up Israel’s battered reputation by arguing ever more vociferously that their state was both Jewish and democratic - and that any dissent was evidence of anti-Semitism. That mantra, quickly adopted by US mediators like Dennis Ross, has become a favourite in the White House.

The problem - at least for the White House and Israel - is that Israel’s Palestinian citizens are potentially a very large fly in that ointment. On the one hand, their visible presence in the democratic process risks undermining the Israeli state’s claims to its exclusive Jewishness; and, on the other, repression by Israel designed to silence them risks bursting its democratic pretensions.

The solution adopted by Israel has been to transform the Palestinian minority into non-citizens, justifying their exclusion on the grounds now being promoted by Washington: that Arabs need first to be educated in the ways of democracy before they can be allowed to participate in democratic processes.

In Israel, the deeds and opinions of Palestinian citizens automatically suffer from a “legitimacy deficit”. This was neatly illustrated while Abbas and Sharon were cementing their relationship at Sharm el-Sheikh. Back in Israel, a parliamentary committee was pushing ahead with a bill to generously reward the few thousand settlers who may be forced to evacuate their homes in Gaza this summer under Sharon’s unilateral withdrawal.

The measure passed by one vote: that of Mohammed Barakeh, the sole Arab member of the committee. It is a rare moment indeed when an Arab’s voice has a decisive effect on the political processes of “the only democracy in the Middle East”. The committee erupted into pandemonium.

Members of the committee opposed to the Gaza withdrawal called Barakeh’s casting ballot “a disgrace”. Their complaints were later taken up by several members of the cabinet, including the education minister Limor Livnat, who called the vote “illegitimate”.

This episode echoed the uproar in 2000 that greeted the previous prime minister Ehud Barak’s intention to stage a national referendum on a proposal to return the Golan Heights to Syria. Critics argued that a majority decision would be worthless, or dangerously divisive, if it relied on a strong Israeli Arab vote. Barak dropped the referendum.

Sharon’s current refusal to countenance a referendum on his Gaza disengagement plan is based, at least partly, on the same racist calculation.

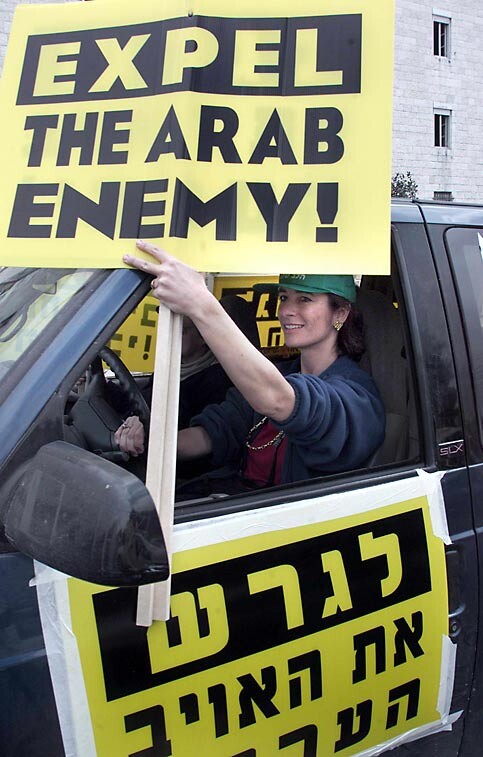

Nadia Matar, head of the extreme right-wing group “Women in Green”, drives a car pasted with Hebrew and English slogans to “Expel the Arab Enemy” during a four-car convoy protest through Jerusalem, 17 March 2002. (AFP/Menahem Kahana)

If Arab citizens are in any doubt that they have not been invited to eat at Israel’s democratic table, there are regular reminders. A Demography Council has been convened inside the government with the express task of finding ways to increase the birth rate of Jewish women to diminish the “demographic threat” posed by the swelling ranks of Arabs - and future Arab voters - inside Israel.

Binyamin Netanyahu, Sharon’s likely successor, and other cabinet ministers have vented their own fears about Israel’s long-term survival if something - it is unclear precisely what - is not done about the country’s Arab population. Rabbis and senior politicians are also frequently given a platform to incite against the minority, calling them a “cancer” or “vermin”, while the attorney general looks the other way.

The country’s law chief is far less indulgent of the country’s Arab leaders, however. The most visible - Azmi Bishara heading the nationalist camp, and Sheikh Raed Salah fronting the Islamic camp - have each been subjected to what were effectively show trials. In both cases, after lengthy media campaigns linking the defendants to terror organisations, the cases all but fizzled out.

Sharon himself has floated as a trial balloon - again following in the footsteps of his predecessor Barak - the idea that in a final settlement some Arab towns inside Israel might be swapped for West Bank territory that includes the largest Jewish settlement blocs. As Sharon is no fan of Palestinian statehood, most in the minority assume he is warning them not to take their Israeli citizenship for granted.

So what kind of civic education is Israel really giving its Arab citizens? Or its Jewish citizens? Or for that matter the Palestinians living under the boot of its occupation? One thing is for sure: democracy will not be its fruit.

Related Links

Jonathan Cook is a journalist whose work has appeared in the Guardian, International Herald Tribune, Al-Ahram Weekly, and other newspapers. Based in Nazareth, Cook is an occasional contributor to EI. He is currently writing a book on the Palestinian citizens of Israel.