The Electronic Intifada 16 February 2005

Rubble.

When Stephen Eric Bronner, Professor of Political Science at Rutgers University, spoke to a conference on Palestine at the University of Minnesota in April 2004, his message boiled down to one word: Rubble.

Bronner had just returned from a fact-finding trip to Israel/Palestine, where he had a chance to view the aftermath of “Operation Defensive Shield,” the euphemistic name given to Ariel Sharon’s brutal 2002 invasion of Palestinian communities throughout the West Bank.

“People would ask me to describe in a sentence what I had seen,” recalled Bronner. “I would tell them that I don’t need a sentence — I can sum it up in a single word.”

Rubble.

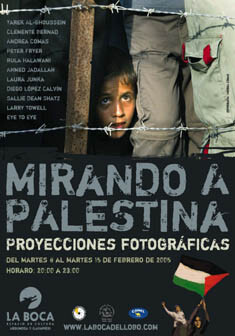

The exhibition poster

The work included in “Looking Toward Palestine” represented an impressive diversity of styles and subject matter, but the common denominator — appropriately, given the reality on the ground in Palestine — was the rubble. This is not to say that the photographers failed to explore other themes. On the contrary, the show was full of images of funerals, children’s games, Israeli tanks and bulldozers, living rooms, violent confrontations — in short, the stuff of daily life under occupation and in the diaspora. The rubble, however, was never far from view.

And looming over all of it, whether sneaking in from the side or imposing its concrete logic on the center of an image, was the Wall. In one of Lopez Calvin’s images, Palestinians project a movie onto it. In other images, the Wall becomes a canvas for graffiti or the cold, unforgiving barrier marking the outer boundary of an impromptu playground.

Nor is it the only barrier. The exhibition is peppered with shots of fences, barricades, barbed wire, checkpoints, and people peeking out of windows. Peter Fryer’s photos, focusing on the plight of families that were separated between Palestine and Lebanon in 1948, contain no physical barriers, yet the windswept desolation of the rural poverty captured by his lens testifies to another kind of barrier. All of these images underscore the significance of what Sylvere Lotringer, Paul Virilio’s frequent interlocutor, has called the phenomenon of “confinement under an open sky.”

Most striking, however, are the images produced by Rula Halawani, a Birzeit University professor and freelance photographer. In a series of photos titled “Negative Incursion,” Halawani uses negative images to document the 2002 Israeli invasion. The result is ghostly and nightmarish: a dark world of devastation that bears a striking and disturbing similarity to the sorts of images produced through the “night vision” goggles that give the U.S. military an advantage over its poorly-equipped foes. Halawani’s decision to employ negative black-and-white images leaves the viewer wondering whether the images were shot in 2002 or 1982 or 1948. Which is precisely the point: the nightmare continues.

A second series of Halawani’s photos, “The warm light still there,” showcases the artist’s native Jerusalem at night, and the contrast with “Negative Incursion” couldn’t be more marked. As the titled indicates, Jerusalem is a place of warmth for Halawani, who takes advantages of the few light bulbs present to cast a loving glow on the deserted streets of the Old City.

Equally notable, and perhaps even more powerful by virtue of its small scale, is “The Intimacy Series,” in which Halawani’s camera captures a series of what would otherwise be innocuous daily interactions: the exchange of identity cards between Israeli soldiers and Palestinians at Qalandia checkpoint. There are almost no faces in the photos, only hands, endless hands, exchanging, demanding, complying, hesitating, waiting, pointing. In these images Halawani focuses the viewer’s gaze on a theater of gestures in which the larger script of power and resistance is written in miniature every time a Palestinian undertakes the simple act of moving from place to place. It is the micro-economy of apartheid. (Note: Many of the Halawani images featured in the Madrid exhibition are available on the web at http://www.virtual-palestine.org/jerusalem/rula1.htm.)

Viewers at the exhibition (John Collins)

The timing of the exhibition also provided an interesting juxtaposition for Spaniards who came to see it. As it happens, the three major news stories in recent days in Spain have all involved rubble (in Spanish, escombros). Residents of a Barcelona neighborhood were shocked on January 27th when a gigantic hole suddenly opened up in the pavement, the unintended effect of a municipal project to dig a new tunnel as part of subway renovations. Many buildings were dangerously destabilized, their inhabitants forced to flee their homes without the chance even to gather their belongings. Over one thousand people were left homeless. On February 9th the Basque separatist group ETA planted a bomb outside a Madrid office building, blowing out windows and causing numerous injuries. Four days later came the towering fire in the Windsor building in Madrid, which gutted the skyscraper and left it looking like a much taller version of the countless Palestinian buildings that appeared in the photo exhibition with their facades pockmarked or even sheared away entirely.

“The tradition of the oppressed,” wrote Walter Benjamin in 1940, “teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule.” Even in Madrid, where the escombros are still falling, at this writing, from the shell that remains of the Windsor, it is easy to forget the lesson contained within Benjamin’s memorable sentence. Exhibitions such as “Looking Toward Palestine,” however, offer ample reminder that the emergency continues, and that it is our emergency as well.

John Collins is Assistant Professor of Global Studies at St. Lawrence University. He is the author of Occupied by Memory: The Intifada Generation and the Palestinian State of Emergency (NYU Press, 2004) and the co-editor of Collateral Language: A User’s Guide to America’s New War (NYU Press, 2002). He is currently living Madrid and doing research on the Palestinian solidarity movement in Spain.