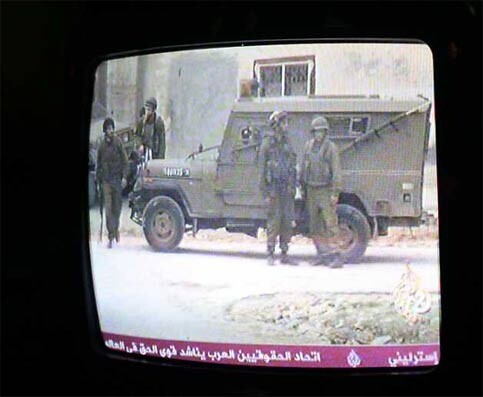

Soldiers in the streets of Saida during the curfew. (Photo: Donna Mulhearn)

27 January 2005 — I am writing this by candlelight in a family living room in the Palestinian West Bank town of Saida where I am currently under military-enforced house arrest, along with 3,500 others. The living room of my adopted home is packed full of people. Grandma with the white scarf and wise face and several of her 13 children: four cheerful sisters with their various tribes of children, three younger brothers and several cousins.

They have no choice but to stay inside. If they open their front door they will be confronted by the machine gun of one of the hundreds of heavily armed Israeli soldiers who invaded and occupied this sleepy farming town three days ago.

It is dark and cold but for the glow of the kerosene heater and two candles on the coffee table. That’s because the army has cut the electricity. The women offer us coffee and a meal despite the fact that they haven’t been able to shop for groceries. The shopkeepers were warned that if they open their shops they will be bombed.

This family begged us to stay with them in their home after being terrorised for several nights by the military. They figure that if internationals are present, then insha’allah, the soldiers will not smash their valuables, beat them or kill someone. But their greatest fear is that their home will be bulldozed, as is the fate of so many other Palestinian homes.

Tomorrow we enter the fourth day of the military occupation of this town. It has thrown the lives of thousands of human beings into chaos, although I’m quite sure it hasn’t made the news at home because no ‘white’ people are involved.

I am here with three other internationals; two British women and a Canadian man. We are here to bear witness to this invasion and occupation, monitor the human rights abuses (of which there are many), advocate on behalf of the people, deliver food and aid and intervene in heated situations.

Despite the regular threats from machine gun wielding young soldiers, we have made a decision to defy the 24-hour curfew that has imprisoned these people in their homes. They cannot go on their balcony let alone go to their jobs, to the shops in the next town or to work their land.

The invasion of this town is an act of collective punishment, which is deemed a war crime under international law. The military says they are searching for wanted people of which there are allegedly eight in this town.

After three days of heavy shelling, gunfire and house searches they have not managed to find any wanted men but have managed to terrorise little six-year-old Rihab who hides under the table when she hears the soldiers come, the 75-year-old woman who begged us for bread today and Nasser a 21-year-old student who cannot get out of the town to get to University.

Six-year-old Rihab hiding under the table with her brother. (Photo: Donna Mulhearn)

So we defy the curfew, not only because it is illegal, but because human beings are locked behind doors need food, medication and many other things to survive. We are busy walking through the deserted streets where the people call to us from their windows and rooftops. We can see by their faces that they are relieved to see us. They tell us what they need and we try to find it somewhere and deliver it. One man begged us to accompany him as he fetched feed for his goats. We also enter homes to hear their stories and tell them that some people are concerned for them.

Saida residents relieved to see us. (Photo: Donna Mulhearn)

I don’t know how many days it will take before anyone notices that this little town is being seriously harassed by Israeli Government-sanctioned terror.

I don’t know how many invasions, humiliations, deaths it’s going to take before the world leaders realise that to achieve peace in the Middle East, it takes goodwill from both sides.

In the information age, Palestinians can watch the occupation of their towns live on their television sets. (Photo: Donna Mulhearn)

After all the rhetoric from politicians about peace following the Palestinian election, the people of Saida could be forgiven for being a little disillusioned. They have not seen any goodwill from their potential partners, but rather the barrel of a gun that has removed their freedom for three days now, and for how many more days, we do not know.

29 January 2005 — Saturday: It’s now day five of the military occupation of Saida village and the frustration, impatience and desperation of the local people is palpable. The sense of powerlessness, which sits within everyone, is heartbreaking.

The 3,500 residents of this West Bank town were collectively kidnapped at 7am on Tuesday morning when an army of tanks and armoured military jeeps took over the town. Loudspeakers were used to broadcast the command: no one leaves their home or lethal force would be used. It was as simple as that. Strategically placed snipers on rooftops enforced the rule with great success. So for the next four days the families had to survive on whatever they had in the house.

No man could go to work. No woman could go to the shops; indeed no one could open a shop! No one could go to check on relatives. No one could go to a Doctor. No grazier could feed their livestock. No farmer could tend the crops. No visitor to the town could leave. To look out your window was to risk your life. Imagine.

On day four the hunger set in. Many cupboards were bare and people needed food. This military operation was becoming a humanitarian disaster.

As we moved about the town asking for people’s needs, they asked for the most basic: “please, can you make the soldiers leave so we are free to leave our home safely?”

Feeling helpless, we phoned anyone we could think of that could help end the siege or who had connections with anyone who could help. The lobbying that had begun on day one resumed in earnest. Israeli human rights groups led the way in applying pressure to military commanders and members of the Knesset, Israel’s Parliament.

It seemed with all the national and international focus on the action in the Gaza strip, little Saida in the West Bank, under siege and starving, had been pushed aside and forgotten.

Finally, late yesterday afternoon there was a small breakthrough. The town was still under military occupation and it was still cut off by roadblocks from the outside world, but the home curfew was temporarily lifted.

When the announcement was made, people gingerly started to step outside and then later began to stream out of their doorways. The streets were full of relieved, smiling people, greeting each other with big hugs and handshakes with a cry of El-Hamdilallah (thanks to God!). It felt like New Years Eve.

Happy in the streets after most of the Israelis had left. (Photo: Donna Mulhearn)

The shops became crowded and farmers rushed to their starving animals to assess the damage.

But the army made it clear they were still in control of Saida. The temporary reprieve was on shaky ground. Armoured Jeeps still patrolled the town, blocked off streets and several houses were still occupied by soldiers.

Upon enquiring, some soldiers told us that the curfew would be lifted for 24-hours, but could be imposed again at any time if there was any ‘trouble’.

But the greatest frustration; there was still no freedom of movement to leave the village.

Queues of people formed at the checkpoint who had been trapped in the village and needed to leave. They were refused.

Twenty-one-year-old Nasser was one of the most desperate; he had to get to Nablus to sit for his final exams at University which start today. Now he would miss out and perhaps jeopardise his upcoming graduation.

There’s also a band of final-year school students eager to make it for the first day of classes at the senior high school in neighbouring Elhar village. They can’t get out, nor can the teachers at Saida Primary School get in, so the school was deserted.

And then there’s Ahmed, he drives the school bus for the nearby town of Tulkarm. The school term resumes today, but he won’t be there to do the rounds for the first day back after holidays.

Many others need to go outside the village for work or business. They are now loosing wages, opportunities and perhaps their jobs.

They’ll be stuck in the confines of Saida, now a military zone, essentially a prison, feeling nervous, uncertain and isolated.

1 February 2005 — Good news: the 24-hour curfew on Saida village has been lifted and the barricades removed from outside the town.

Not so good news: the military is still there. Soldiers continue to occupy the homes of several families and do regular patrols of the narrow streets in the armoured jeeps. The people are still nervous.

We read in the media positive reports that the Israeli army will withdraw from its operations in four West Bank towns, including Tulkarm which is the area of Saida village. The pullout is to begin tomorrow, according to the Israeli Government. We will monitor the situation and hopefully will see this withdrawal occur.

I encourage anyone to write to their foreign ministers and to the Israeli Government to welcome the military withdrawal from West Bank towns and suggest further moves such as dismantling of checkpoints and the other apparatus of occupation.

Donna speaking with a Palestinian family in Saida. (Photo: Donna Mulhearn)

Related Links

Donna Mulhearn, an Australian journalist and peace activist lived in occupied Iraq where she worked as a volunteer aid worker establishing a shelter for street kids and orphans. She is currently in occupied Palestine.