The Electronic Intifada 17 September 2004

Sabra and Shatila survivors still await justice 22 years later

The September remembrances — and forgettings — are upon us once again.

For the last time, the families of those who perished at the World Trade Center in Manhattan on September 11, 2001 were able to physically visit the site of that unforgettable crime. Next year, large-scale construction projects will prevent them from gathering at the place where their husbands, wives, sons, daughters and parents took their last breaths. September will always be a painful month for them, and the lack of any clearly marked, individual graves to tend and visit throughout the years will undoubtedly augment their suffering. Still, in the ranks of the millions of people bereaved by crimes against humanity, which the attacks of 9/11 surely were, they are relatively lucky. They know exactly what happened to their loved ones, and they know that their suffering was not sadistically prolonged over hours or days, nor was it accompanied by the humiliation of imprisonment, rape, or torture.

And they are relatively fortunate, too, in enjoying the solidarity and support of an entire nation, and indeed much of the world, which shares their sorrow and outrage at this mass murder of innocent civilians. The memory of what happened on September 11, 2001 is not likely to fade from public ceremonies or political discourse anytime soon. No one can or should bury that black day or minimize its significance. Legal action can, and will, be taken. The narrative of what happened that Tuesday morning three years ago has been carefully recorded by official commissions of inquiry. Off-Broadway plays, movies, and popular music have immortalized the dead. Armies have been dispatched to search out the masterminds of the crime. 9/11 is now an icon, a myth, a cause; it will probably be viewed, decades hence, as a momentous turning point in US and even world history, though whether for good or for ill is still unclear.

But silenced September memories prove that death is not such a great equalizer after all. Some victims inspire action, while others seem to inspire amnesia or apathy. For the survivors of another September massacre, this week is just business as usual. 2004 brings few memorials, no newspaper headlines or CNN specials, no investigations or prosecutions, no historic developments or grand narratives galvanizing the world to right a wrong and apprehend the guilty.

Why the differential treatment, they must wonder. Perhaps what they suffered was not really a crime against humanity? Or maybe they are not actually part of humanity? Surely there is an explanation. In the Palestinian refugee camps of Beirut, the 22nd anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila masssacre marks just another day of struggling along in substandard housing, coping with high unemployment, chronic poverty, poor health, an absence of adequate social services, bleak visions of the present, fears of the future, and searing memories of the past.

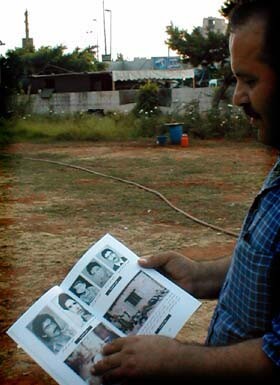

Mahmoud Abdallah Kallam displays portraits of victims of the massacre in his book, Sabra and Shatila: Memory of Blood. They are now buried in the mass grave behind him. Thanks to volunteers’ efforts, the mass grave is now planted with roses and surrounded by young olive saplings. (Laurie King-Irani)

Those who survived the massacre remember 50 hours — September 16-18, 1982 — of terror and agony as Christian Phalange-affiliated militiamen infiltrated the camps under Israeli protection and with Israeli assistance, including the Israeli Defense Forces’ launching of night-time flares to expedite the carnage. The camp exits were sealed off by the IDF, so very few could escape, though many pleaded desperately with Israeli soldiers as the murderers systematically rounded up men, mutilated children in front of their parents, raped and disemboweled pregnant women and gunned down entire families, leaving alleyways full of blood.

By the time journalists and aid workers were able to enter the camps on the 18th, they found a silent city of bloated corpses, the nauseating stench of death, and the deafening drone of frenzied flies. A bulldozer, that now-infamous tool of Israeli occupation, had been hastily brought in to cover hundreds of bodies, but many still lay where they fell, on the streets, in doorways, under tables, and crumpled like rag dolls at the foot of a wall where executions had taken place. Even horses, dogs, and cats were slaughtered. A complete and total carnage. A professional job entailing no small amount of coordination and cooperation. This did not “just happen.”

The 1000 or more victims of the Sabra and Shatila massacre are just a small percentage of Palestinian victims of grave violations of international humanitarian law stretching back more than half a century. Buried in a mass, unmarked grave that until 2002 also served as a garbage dump, the dead of Sabra and Shatila were murdered a second time last September with the final crushing of a landmark legal effort by 28 massacre survivors to seek justice in a Belgian court. Thanks to pressures brought by the United States and Israel, which included threats to move NATO headquarters from Brussels to Poland, the Belgian Parliament decided to gut its progressive universal jurisdiction legislation, which had offered hope to many seeking to end impunity for the worst crimes known to humankind.

The Sabra and Shatila survivors had used Belgium’s 1993 “anti-atrocity law” to lodge a case in a Brussels court against then-Israeli Defense Minister and Commanding Army General Ariel Sharon, his assistant General Amos Yaron, and other Israelis and Lebanese responsible for the massacre under the principle of universal jurisdiction. They did not seek monetary compensation, vengeance, or regime change, just an end to impunity for the architects of the crime, justice for the dead, and closure for the living. The case hinged upon Sharon’s Command Responsibility for all that happened in Beirut given the Israeli Defense Forces status as the Occupying Power in that city after a summer of invasion, aerial assaults, siege, and combat.

The principle of universal jurisdiction, encoded in the Fourth Geneva Convention, international customary law and the 1984 Convention on Torture, is based on a consensus, strengthened by the horrors of World War II, that some crimes are so heinous that they threaten the entire human race. The jurisdiction for prosecuting these crimes must be universal, not simply territorial. The Geneva Conventions specifically state that all signatories to the convention have not only the right but indeed the duty to either prosecute or extradite individuals guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. In 1993, the Belgian Parliament formally incorporated the principle of Universal Jurisdiction into Belgium’s criminal code, thereby enabling Belgian courts to hear war crimes cases having no connection to Belgium. In February 2003, the Belgium Supreme Court had ruled that the Sabra and Shatila plaintiffs had a valid case and that a legal investigation and prosecution should begin.

One of the unanswered questions that many hoped to address in the Sabra and Shatila case was the fate and whereabouts of hundreds of men and boys rounded up during and after the massacre in the nearby sports stadium, where Israeli officers were present and clearly cognizant that civilians were being separated from their families, interrogated, and trucked away by a Christian militia infamous for atrocities. The disappeared of Sabra and Shatila, who included Lebanese as well as Palestinians, have never been seen since. Their families would like to know where their bodies are.

Despite an admirable international concern for exhuming mass graves in Iraq, Bosnia, and Kosovo, dispatching teams of forensic anthropologists to discover the final resting place of hundreds of Palestinians and Lebanese abducted and murdered at a time when Ariel Sharon had command responsibility for all events that took place in West Beirut, including the refugee camps, does not figure high on anyone’s priority list. (And it must be noted that approximately 17,000 Lebanese who disappeared and/or were kidnapped during that country’s 1975-1990 war are also still missing, and all attempts thus far to inquire as to their whereabouts have been quashed. The fact that much of Lebanon comprises unmarked graves of the lost and forgotten is a damning monument to impunity for crimes against humanity, and a situation requiring remedy as soon as possible. Lebanon can never hold its head up until it addresses the impunity of those responsible for these disappearances, many of whom, unfortunately, have become important political figures in post-war Lebanon.)

With last September’s rescinding of Belgium’s progressive anti-atrocity legislation and with it the suspension of a proper legal investigation by neutral and qualified parties, we may never know where the graves of the disappeared are. The lawyers for the Sabra and Shatila plaintiffs are now appealing to the European Court of Human Rights to investigate the Belgian government’s failure to respect and recognize the “separation of powers” principle that prohibits the executive branch from interfering with the judicial and legislative branches of government. Michael Verhaeghe, one of the lawyers for Sabra and Shatila survivors, stated this week that:

“Together with a couple of other politically embarrassing cases, our case was singled out by the Belgian government when they agreed, on the occasion of the new government’s formation in July of last year, to new legislation designed to eliminate specific cases such as ours. This was even expressed clearly during the debate in parliament. We believe this is an intolerable intrusion of the executive branch in the affairs of the judicial branch, and particularly in our case, especially after the courts had ruled it admissible, even up to the Supreme Court. Such an intrusion resulted in the violation of the ‘fair trial’ provision of Article 6 of the European Convention on the protection of Human Rights.”

So legal avenues are not yet entirely exhausted.

This week, as the survivors of one of the worst massacres of the post-World War II era remember their dead and cope with their chronic nightmares, Ariel Sharon, the man found to be “personally responsible” for the massacre by Israel’s 1983 Kahane Commission, is planning an official visit to Europe. He will be travelling to Holland, which will hold the presidency of the European Union for the rest of 2004.

Sharon will undoubtedly be received as an honored guest in this great nation, which is home to the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia at the Hague. When Ariel Sharon steps off the plane, he will be treading not only on Dutch soil, but also on the bodies of the dead of Sabra and Shatila. Legally, the massacre and its victims remain unburied. It is Holland’s shame to assume that rolling out a red carpet of welcome can cover the corpses of Mr. Sharon’s victims, whose numbers continue to climb with each passing day.

Should any Dutch citizen or political official wish to take the Geneva Conventions seriously and demonstrate support for the global campaign against impunity for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, they might want to arrest a man who had clear and unequivocal command responsibility for a vicious massacre that the Supreme Court of Belgium, another EU member, found worthy of judicial investigation under the principle of universal jurisdiction.

Or, in this month of remembrances, they can just forget.

Laurie King-Irani, a co-founder of The Electronic Intifada, served as North American Coordinator for the International Campaign for Justice for the Victims of Sabra and Shatila (www.indictsharon.net). She is writing a book on the social and political dimensions of universal jurisdiction and the controversies surrounding it.