Palestine Report 6 September 2004

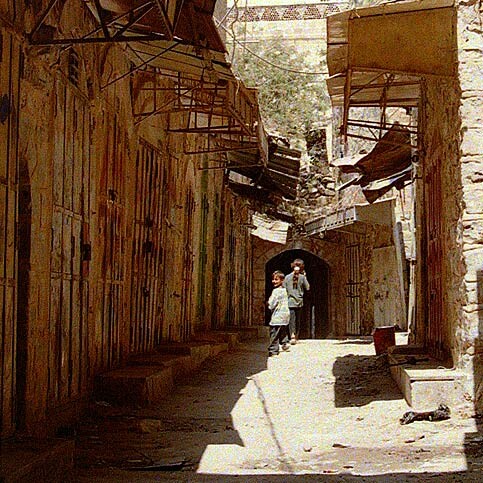

A pattern of targeting the Palestinian economy and the infrastructure that sustains it has been visible for years. Above, children play on the streets of Hebron’s Old City during an Israeli curfew, July 1997. (Photo: Nigel Parry)

ON AUGUST 9, Israeli bulldozers sank their jaws into three buildings in the old city of Hebron. The demolitions, to make way for a settler-only road to connect the Kiryat Arba settlement with the Ibrahimi Mosque, caused an outrage.

The three buildings were ancient, dating back some 500 years to the Mamluk period. The alleys in the Jaber and Salaymeh quarters where the houses were situated and the stone arches above them used to form the southern entrance to the old city.

“These three buildings were part of the structural fabric of Hebron’s old city and part of the historical environment surrounding the Ibrahimi Mosque,” said Imad Hamdan, public relations director for the Hebron Reconstruction Committee, in an interview with the Palestine Report. “It seems the occupation forces ignored this fact. They tore down these historical buildings in order to build a settler road which they are calling ‘Worshippers Road.’”

The demolitions were denounced by the highest official circles. Prime Minister Ahmad Qrei’, in a statement released by his government on August 10, called it a “true crime by the occupation against the Palestinian people.” Israel, he said, demolished these historical sites with no regard to humanity or civilization.

Hamdan believes Israel is waging a war on the heritage of Hebron’s old city, pointing to the fact that there are tens of other houses slated for demolition, some of which date back to the Mamluk and Ottoman eras and others that were built during the British Mandate. It is a clear indication to Hamdan of an Israeli attempt to Judaize the old city and the area around the Ibrahimi Mosque.

“This new settler road will pass through the Wadi Nasara, Jabaer and Salaymeh quarters and the neighborhoods east of the Ibrahimi Mosque,” explained Hamdan, but pointed to an existing road, also off-limits to Palestinian motorists, which runs a similar route and is only 150 meters longer. “The difference is only 15 seconds in any car,” he said. “Their ‘security concerns’ are already being addressed by the existing road.”

A loss of centuries

“These violations are aimed at imposing facts on the ground through settlement expansion at the expense of the property of residents in the old city and its surroundings,” said Areef Jabari, Hebron governor. “What happened is a disaster that can never be rectified. We can never bring back the ancient houses that were torn down. With them, almost six centuries have been lost.”

According to international law, an occupying power is responsible for preserving the cultural property of those under occupation. Indeed, the Hague Convention, which Israel ratified in 1957, specifically calls on an occupying power to refrain from any hostility directed against such property and from any use of such property or its surroundings for military purposes.

Since the end of 2000, an as yet uncounted number of Palestinian heritage sites, from Rafah in the south to Jenin in the north, have been damaged or destroyed during Israeli military operations. Most famously, the siege of the Church of Nativity in Bethlehem in 2002 saw one of the most important sites in Christianity damaged by Israeli gunfire. The damage there, however, pales in comparison to that in Nablus, which has been one of the hardest hit Palestinian cities during the Aqsa Intifada.

The old city of Nablus dates back to Canaanite times. It was described as Shechem in the Tel El Amarna letters 1,400 BC. Some 2,600 buildings in the old city can be dated back to Ottoman times, and some go as far back as the Mamluk and even Byzantine eras.

Over a period of three weeks in December 2003 to January 2004, repeated Israeli incursions into the old city of Nablus left several historic houses and buildings as well as archaeological sites destroyed or damaged. Most notable was the damage to the Abdel Hadi Palace and the Kakhn, Sadeq and Shabi homes in the Qaryoun neighborhood. Israeli forces also destroyed the eastern wall of the Salah Mosque, which was previously a Byzantine church, and the Khadra’ Mosque, previously a Crusader church.

“The destruction in Nablus has been concentrated mostly on buildings in the old city,” Naseer Arafat, president of the Association to Protect Nablus Old Town, told PR. He said the destruction included shops and homes inside the old city, which were either partially or fully destroyed. “Nearly 60 buildings were completely destroyed and an additional 250 were partially demolished. This is in addition to the massive damage done to the old city’s infrastructure. That is our identity they are destroying. Our cultural heritage is our identity.”

The Abdel Hadi Palace dates back some 250 years. It covers an area of over 3,000 square meters and belongs to the well-established Abdel Hadi clan. During the invasion, the Israeli army claimed resistance fighters were hiding inside the houses or in the tunnels that run under the old city, and went house-to-house in search of them.

Their claim was dismissed by Ali Touqan, director of the Nablus library, who said the targeting of the Abdel Hadi Palace was intentional and direct. “They put holes in the walls, a meter thick. They just wanted to destroy it.”

Touqan said Israeli claims of underground tunnels used by resistance fighters were also completely baseless. The tunnels are there, they have been around since the Byzantine era when they were used as water canals, but “under no circumstances could they be used by resistance fighters. These tunnels are a cultural legacy that the occupation has destroyed.”

Targeting identity

“The main goal behind these assaults,” Hamdan Taha, director general of the antiquities department of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities told PR, “is to cause political harm to Palestinians’ cultural identity. This has always been a source of intimidation for the Zionist movement and the Israeli occupation. And the intentional targeting of historical sites over the years is also designed to destroy a component of future cultural, economic development and tourism.”

Taha believes the demolitions in Hebron are just one link in a chain of a deliberate campaign to target symbols of Palestinian cultural heritage. He pointed to over 450 villages that have been destroyed and erased from existence in an attempt to change the historical character of certain places with historical and archeological significance.

If Israel continues this “path of destruction,” said Taha; “Palestinians will have no other choice then to teach future generations about their heritage through pictures and books.” In fact, he continued, his department is preparing for the eventuality. The antiquities department is documenting the damages incurred by these archeological sites, he said, “in order to ensure that this precious legacy is passed down even if Israel succeeds in wiping it from existence.”

Direct damage incurred during military operations is only part of the story, however. According to a March 2004 study released by the Palestinian Institute for Cultural Landscape Studies and prepared by researchers Jamal Barghouth and Mohammed Jaradat, the separation wall being erected by Israel in the West Bank is set to undermine the cultural link between archeological sites in the West Bank and surrounding archeological areas.

The West Bank is one of the richest areas in the world from an archeological perspective. From Canaanite times up, the ancient Greek, Mesopotamian, Persian, Roman, Byzantine and Arab Islamic civilizations have all left traces in the ground.

According to the First Hague Convention, of which Israel is signatory, cultural property includes archaeological finds. But no specific mention is made of archaeological excavations by an occupying power. That was rectified in 1999 in the Second Protocol to the Hague Convention, which specified that an occupying power must act to prevent archaeological excavation in occupied territory. The second protocol entered into effect on March 9, 2004, but has not yet been ratified by Israel.

Barghouth and Jaradat’s study finds that Jewish settlements in the West Bank have directly annexed over 924 archeological sites either now or through future expansion plans. This number will rise, however, to 4,264 sites and archeological landmarks, 466 of them major archeological sites, once the wall is completed. This figure equals 47 percent of all known major sites in the West Bank including East Jerusalem, from a total of 1,084 sites according to 1944 British maps that surveyed archeological sites in the West Bank.

The ideological and historical premise behind plotting the course of the barrier in such a way, said both Barghouth and Jaradat, is that the West Bank is considered the historical and geographical site on which the Israelite tribes settled during the Iron Age around 1000 BC and thus where Judea and Samaria was created.

Between 1967 and 2000, the two researchers said, the northern and central areas and even the Jerusalem area were exhaustively surveyed, enabling Israel to determine the exact sites Jewish tradition deemed important and that should remain under Israeli rule. Thus, added the researchers, it is unsurprising that one of the standards used to define the course of the wall would be archeological sites.

“The wall constitutes a disaster to Palestinian cultural heritage,” said Taha. “In addition to the fact that it will isolate approximately 50 percent of archeological sites from Palestinian territories, it will affect religious tourist activity for which Palestine is famous. The main religious tourist sites are already isolated. Look at Jerusalem and Bethlehem. Travel between these two cities, which for thousands of years has been unhindered, has now become almost impossible for Palestinians.”

Related links: