Arab Association for Human Rights (HRA) 23 August 2004

OFFICIAL REACTIONS TO THE HUNGER STRIKE OF SECURITY PRISONERS REVEAL THAT ISRAEL’S SECURITY NEEDS CLASH WITH THE PALESTINIANS’ RIGHT TO LIFE

In the company of the international community, Israel is generally recognised as the only functioning democracy in the Middle East, and often, the attribute “Western-style” is added to Israel’s system of governance. Notwithstanding the polarising nature of this definition, the term is commonly associated with a participatory political system based on equality and the rule of law. This entails, inter alia, the absence of political prisoners in the country’s jails, categorical rejection of torture as a means of interrogation and a political discourse that refrains from hate speech.

According to the U.S. Department of State Human Rights Country Report on Israel and the Occupied Territories 2003, “there were no reports of political prisoners.” This is due to the fact that Israel has developed a special terminology for persons imprisoned for their political views: within the larger framework of the war on terror and Israel’s definition of homeland security, thousands of Palestinians are being held as “security prisoners”. If one takes a look at the country’s “security prisons”, a different picture unfolds: reports from human-rights organisations record that since the beginning of the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories in 1967, over 650,000 Palestinians have been detained by Israel. This corresponds to a total of approximately 40% of the male Palestinian population of the Occupied Territories; the number of female political prisoners is currently at 120. As of August 2004, approximately 7,500 Palestinian political prisoners are being held in Israeli prisons, military detention camps, interrogation centres and regular police stations. One in ten “security prisoners” is an administrative detainee, without being put on trial or even charged with an offence. 380 prisoners are below the age of 18, 78 of whom are 16 years and younger. More than 3,800 Palestinian “security prisoners” are detained in civil prisons or holding centres operated by the Israeli Prisons Service (IPS). All of these facilities are situated inside the 1948 borders. This in itself constitutes a breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which provides in Article 47 that “protected persons accused of offences shall be detained in the occupied country, and if convicted, they shall serve their sentences therein”.

The Prisoners’ Demands as they are backed up by International Law:

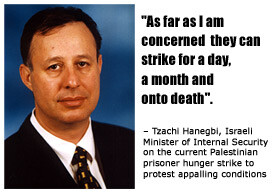

In keeping with a policy of portraying the demands of the prisoners for improved conditions as requests that are opposed to prison order and the security of Israel, the Prisons Service and Israeli officials focus in their public responses to the hunger strike on only a few selected demands. Those are cited without any background information or reference to the conditions that gave rise to the petitions. The prominent demands named in the Israeli and international media as being prerequisite for an end to the strike are for an end to daily strip searches, the removal of the glass partitions separating prisoners from visitors including their own children, and public pay phones for prisoners. Identifying these, Public Security Minister Tzachi Hanegbi said that “giving in to any of the prisoners’ demands would make it easier for terrorists to plan and orchestrate terror attacks from inside the prisons” (indirect quote from Haaretz).

A closer look at the set of demands presented to the Israeli Prisons Service by the prisoners and an open letter from the Committee for the Families of Political Prisoners and Detainees in the West Bank reveals a much wider range of demands, the reasons behind them, and a starker picture of the poor conditions in the prisons. Moreover, the demands made by the prisoners are sanctioned by international law, through guiding principles and in many cases explicit regulations. These can be found in the following human-rights instruments and treaties:

This means that the striking prisoners are demanding rights that they are legally entitled to and the deprivation of which amounts to serious abuse and a pattern of grave human-rights violations.

The United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which was ratified by Israel on the 3rd of October 1991, reinforces the demands to allow prisoners to send out diaries, poems, studies, prose, etc, during visits; to allow prisoners to prepare their own food according to their customs and religion; and not to interfere with prayers or preaching or to punish preachers for what they preach by defending their rights to the freedoms expression and religion.

The Convention also states in Article 10 that “all persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.” Yet the prisoners complain that they and their visitors are forced to undergo degrading and compromising strip searches. The prisoners suggest limiting the number of searches that a prisoner must go through each day/year and carrying out the searches using an electronic device rather that gloved hands as alternatives to the current, unacceptable situation.

The United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhumane or Degrading Treatment, to which Israel is also a party, defines “torture” as any act that inflicts severe mental or physical pain or suffering on a person in order to, among other intentions, punish that person for an act s/he or a third person committed or is suspected of committing. Several of the prisoners’ complaints decry practices that would fall within this definition. For example, the prisoners and their families are asking for an end to arbitrary revocation of visitation rights and extended confinement to cells as punishment for minor infractions such as singing or speaking too loudly and to subjecting prisoners to solitary confinement for excessive periods of time, meaning months or even years. This Convention also addresses the prisoners’ call for an end to all forms of collective punishment.

A third human-rights instrument, which reaffirms in detail many of the petitions of the striking prisoners, is the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, which was issued by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), an intergovernmental body that operates under the authority of the United Nations General Assembly. The rules included in this document reflect general international consensus and set requirements on such points as minimum floor space, ventilation, light, access to washing facilities and toilets, basic hygiene supplies, beds, libraries and up-to-date periodicals, that handcuffs be removed when prisoners meet with administrators, and that women prisoners be attended and supervised only by women officers, all of which are included in the prisoners’ set of demands.

Of primary concern to the prisoners and their families are regular and unhindered visits. The Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners require that special attention be paid to the maintenance and improvement of such relations between a prisoner and his family as are desirable in the best interest of both and also that prisoners be allowed under necessary supervision to communicate with their family and reputable friends at regular intervals, both by correspondence and by receiving visits. Contrary to these standards, Palestinian prisoners being held in Israeli prisons complain that siblings and third level family members are not allowed to visit them, that immediate family members are forced to go through long humiliating ordeals at checkpoints and prison security screenings on their way to visit the prisoners, and that a glass barrier and metal grates prevent them from having close contact with their children and other visitors and often impede communication between them. For this reason, the prisoners are requesting public phones, subject to monitoring, in either their cell blocks or the yards so that they can communicate with family members.

It should also be noted that the illegal internment of Palestinian prisoners from the Occupied Territories within the borders of Israel, which as mentioned previously violates the Geneva Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, contributes to this situation. Relatives wishing to visit the prisoners are barred from doing so by restrictions on movement between the Occupied Territories and Israel, the often arbitrary whims of checkpoint personnel, and the separation wall. Backed up by the Fourth Geneva Convention, the prisoners are demanding that they be relocated to facilities closer to their homes.

A fifth treaty that applies to the situation of Palestinian prisoners, which has received near universal ratification, is the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. According to the Kafkaesque Military Order 1500 put in place during the British Mandate period, children in the Occupied Territories ages 12 and older can be tried in military courts, and a child over the age of 16 is considered an adult, in violation of Article 1 of the Convention which stipulates that “a child means every human being below the age of eighteen years.” It must be noted that Israel keeps to the internationally recognized definition of a child among its own citizens but applies a different standard to Palestinian minors in the Occupied Territories. In practice, a child from the West Bank or Gaza can be sentenced to six months in prison for throwing a stone. Additionally, minors are often held together with adults and criminal offenders, a practice that their families strongly protest and that is forbidden by numerous international regulations including those found in the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Other major goals of the hunger strike are to end arbitrary and indiscriminate beatings and the firing of teargas into cells and to gain access to proper medical care including necessary surgical operations and equipment for measuring blood sugar levels and blood pressure. In discounting the petitions of the prisoners and arguing that giving in to their demands, which include contact with spouses and children, beds to sleep on, and even toothpaste, would make it easier for them to organise terror attacks, Minister Hanegbi and other official persons and bodies are appealing to the catchword of security in an attempt to shirk their responsibilities and obligations under international human-rights law.

Our Invitation for Cooperation with the International Community:

Israel’s political establishment ignores the humanitarian and human-rights dimensions involved by dismissing the hunger strike as a security matter and the prisoners themselves as security threats. Minister Hanegbi made this attitude more than clear by noting that he would rather have the Palestinian prisoners “starve to death” than to give in to their demands. Even more worrying is the fact that prison officials have taken concrete steps to oblige the Public Security Minister by confiscating the salt that prisoners had stowed away to prevent themselves from becoming dehydrated during the strike. Other “strike breaking” measures under way are restrictions on the sales of sweets and cigarettes and efforts to whet the prisoners’ appetites by grilling meat and baking bread outside their cells.

For the time being, Minister Hanegbi’s comment is the last in a series of remarks by Israeli intellectuals and government officials that point towards the idea that the very existence of the Palestinian people poses a security threat to Israel. In May 2004, the Arab Association for Human Rights (HRA) published “Let Them Suffocate”, a report on excessive police violence during house demolitions in the Galilee (Israel). The title of the publication quotes the words of a policeman, referring to Arab children in a kindergarten where tear gas had filtered in. The HRA is deeply concerned about the fact that hate speech by state officials, which constitutes a death wish to a person or members of a group, is not challenged by the Israeli general public but rather acknowledged with approving silence.

The state of Israel is in severe neglect of its duties as a declared democracy, and the treatment of Palestinian prisoners is an appalling manifestation of this negligence. Specifically, the resolution of Minister Hanegbi, to let the prisoners starve to death rather than comply with their demands for more humanitarian treatment, clashes with his mandate as Minister of Public Security to protect the rights to life, dignity, and security of person of all those under his charge. The Arab Association for Human Rights expresses its solidarity with the Palestinian political prisoners - both from inside the Green Line and from the Occupied Territories - and supports the humanitarian demands put forward by the detainees. We further call upon the members of the international community to take these grave human-rights violations into account in their diplomatic relations with Israel.

For our community, the Arab minority inside Israel, it is of critical importance to make human-rights concepts tangible and to show that international norms are actually being applied in people’s everyday lives. To this end, the HRA would be pleased to cooperate with members of the international community to endeavour to translate formal commitments in this area into actual implementation by contributing our research and advocacy expertise in human-rights issues concerning our constituency as well as by providing first-hand information on topics related to our work. We would also like to extend an invitation for all those in the area to join the HRA in a solidarity hunger strike on Wednesday August 25, from 9:00 a.m. until 7:00 p.m. at the protest tent next to Mary’s Well in Nazareth.

For further information, please contact us directly:

Arab Association for Human Rights (HRA)

PO Box 215, Nazareth 16101, Israel

telephone: +972 (0)4 6561923

fax: +972 (0)4 6564934

email: mzeidan@arabhra.org; hra1@arabhra.org

Related Links