The Electronic Intifada 29 July 2004

The Unisphere at the 1964 World’s Fair.

On the decline of some American dreams

I don’t know a soul who’s not been battered

I don’t have a friend who feels at ease

I don’t know a dream that’s not been shattered

or driven to its knees

but it’s alright, it’s alright

for we lived so well so long

Still, when I think of the

road we’re traveling on

I wonder what’s gone wrong

I can’t help it, I wonder what has gone wrong

— “An American Tune,” by Paul Simon

A gleaming chrome heat. August 1964 in New York City. “Lean over and look up, honey; that’s the Empire State Building! The tallest building in the world!” I lie down on the scorching hot leather of the back seat of our 1960 Ford and twist my five-year-old head to gaze up according to my father’s instructions.

A towering grey building looms impossibly large against a cloudless sky. Outside I can sense something immense and endless humming all around us. My first experience of a big city — the big city: New York. This was nothing like the small town we lived in: Greensburg, Pennsylvania. New York was an engine of humanity, color, odor, and ideas all blending into something greater, grander and faster. In what was probably my first experience of patriotism, I felt my heart swell up with pride. This was what America was all about, and here we were—right in the middle of it, even a part of it!

We had come to New York City after visiting my mother’s large family in New Jersey, where we had made a pilgrimage to the legendary “shore.” My younger sister, upon rushing into the ocean for the first time, exclaimed that the Atlantic tasted “just like pretzels!” An aunt took me by the hand and told me to look out at the big ships on the horizon and to imagine how our grandparents and great-grandparents had crossed the enormous ocean leaving behind Ireland, Wales, and Lithuania to find a good life in America. My spine tingled at the thought of crossing something so great as that green mass of water. I felt awe that people related to me had actually done this.

We were in lower Manhattan on our way to the World’s Fair, a panoply of the world’s people, cultures, arts, inventions, foods, and music framed by a space-age, univeralist theme —“the unisphere” — and heralded by a catchy song I loved that summer: “It’s a small world after all!” Good training for a future anthropologist.

African delegates posing under the Unisphere at the 1964 World’s Fair. (NYPL)

What I remember most about the World’s Fair was that we waited in a lot of long lines in steamy heat, and that I had started arguing with a graceful and lovely Indian woman in a dark green sari at the India pavillion that if her people were starving, they should really be allowed to eat hamburgers. People should be more important than cows! My first taste of ethnocentrism and self-righteous indignation.

After that, I remember wandering with my mother toward a knot of young, dark-skinned men who were holding signs and chanting. My mother began talking to a man in his early twenties with beautiful black hair, slicked back like thick silk from his temples. He was wearing a crisp buttery-yellow short-sleeved cotton button-down shirt, and seemed very upset as he spoke urgently to my mother in accented English. I sensed he was in some sort of trouble.

Years later my mother reminded me, upon my return in 1982 from a two-month archaeological dig in Jordan and a three-week stay in Jerusalem and the West Bank, of this long-ago World’s Fair experience. “They were Palestinians,” she recalled. “They were protesting and I wanted to know what was going on, so I asked one of the guys and he said they had lost their homes, and that we shouldn’t believe the information at the Israeli exhibit. They did not have their own exhibit for Palestine, obviously. I wanted to know more about them because of the beautiful script on the signs they were holding. Later, when I saw pictures on television of Palestinians carrying all their stuff with them over a bridge after the 1967 war, I thought of those guys at the World’s Fair, and what they’d said to me, and I also started to wonder: Would the Israelis now do to these people what the Nazis did to them?.”

I’d gone to Jordan inspired by the same thing that had led my mother to approach that group of young Arab men in New York two decades earlier: Arabic calligraphy. From 1979-81, I’d been a waitress in an Arabic restaurant in Pittsburgh and had asked my co-workers to teach me their language after I grew intrigued by the framed passages of the Qur’an on the restaurant’s walls. My trip to Jordan was the first time I’d left the United States, and I discovered that the world was not much of a “unisphere” after all: historical injustices and social inequalities are harder to ignore when they come with names attached: Muhammad, Fadia, Ahmed. One thing was for sure: Palestinians were still protesting in front of official renderings of history and morality.

Chief among those official renderings is an attempt to put as much distance as possible between Americans and Palestinians, between US and Arab-Islamic societies and histories. Unbridgeable differences. Unfathomable mentalities. Undemocratic governments. Uncivilized men. Unfree women. All these definitions help us hone a mythic American identity and mission: forward looking, rational, freethinking, charitable, friendly, fair-minded, square-dealing, honest brokering, and above all: just.

And this icon, this myth, has traveled far and wide and inspired a lot of people, not just Americans, but also Arabs. In fact, one would be hard-pressed to find any people more receptive to the American dream than Palestinians and the Lebanese. While living and working in Beirut in the mid-1990s, I heard again and again from my friends and co-workers that America was the ideal, the hope, and the model. Though they may have hated many US foreign policies, Palestinians and Lebanese admired the principles upon which the United States was founded. They hoped that the US commitment to justice, fairness and equality would eventually be brought to bear on the Palestinian issue, and two years into the Oslo era it did not seem all that far-fetched to think it might just happen.

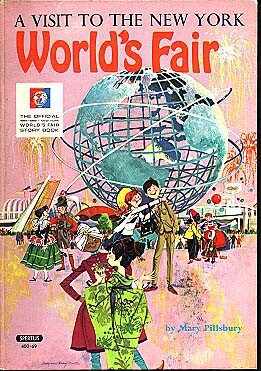

A children’s book about one of the themes of the 1964 New York World’s Fair: “Peace through Understanding.”

Because it represents a failure to be just, fair, forward-looking and charitable, the US treatment of the Palestinian people represents a failure to be American. Palestine is not a sideshow in the current frightening uproar of political events in the world. It is the main event for Americans and for America. Palestine can and should be the proving grounds for all the values and principles — freedom, dignity, prosperity, justice, and fairness — that set the United States apart from other countries for decades.

It is hard to fathom how and why so many decent Americans remain indifferent to, and even supportive of, the daily cruelties committed in their name, and with their tax dollars, in Palestine. Partly this negligence is due to media malfeasance of the sort our website was created to counteract. Some people still don’t get it: If they are not outraged, perhaps they have not been paying attention.

But American indifference is also a defense mechanism. Questioning US and Israeli policies would entail questioning a much wider set of assumptions, including those centering on the current US involvement in Iraq and the hard and fast line supposedly dividing the Good from the Evil and other manichean notions underpinning US and Israeli actions.

At a deeper level, though, perhaps US audiences see in the faces of Palestinian men, women and children pressed against walls of hate and racism the damning reflections of the Sioux, Lakota, Mohawk, and Iroquois men, women, and children upon whose bodies the United States of America was built. Instead of thinking “Here is an opportunity to prevent another country from making the same mistakes, from causing the same suffering,” have US citizens and policymakers decided to hide from what Israel is doing in order to keep hiding from themselves what was done to the native population of this continent? As admirable as the United States is and can be, let no one forget that it was founded on a genocide. If possible, we Americans should counsel others against following such a path.

Or is it the religious-fervor element, more pronounced in US politics since 9-11 and the presidency of George W. Bush, who likes to present himself as a “godly” man and a good friend and supporter of that “man of peace” Ariel Sharon, no matter how many laws he breaks? Religious fundamentalists flourish now not only in Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, but in Washington, DC and Jerusalem, too. Mixing prophecy and politics is profoundly un-American. It’s also a matter of heated debate in Israel, where the majority of Israelis cast a jaundiced and cynical eye upon any misuse of the Torah to defend land grabs. Most Israelis do not support the settlements and would gladly see them go. You would never guess this from listening to US media, however. One wonders if John Kerry has heard the news.

If the Bush administration finally succeeds in taking down the American dream, it will do so while also taking down the dream of the 1964 World’s Fair’s “unisphere,” a common world of peace and understanding and prosperity for all, a shared world governed by international laws, a world that welcomes an International Criminal Court and global environmental accords. And we will all be the poorer for it, whether we are Americans, Israelis, or Palestinians.

That hit song of forty summers ago bears reconsideration: “It’s a small world after all, a small world after all.”

Anthropologist and EI co-founder Laurie King-Irani is spending her summer taking hip-hop dance classes. She is also writing a book on Belgium’s experiment of practicing the principle of universal jurisdiction.