The Electronic Intifada 25 September 2003

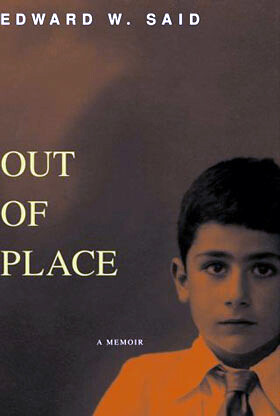

The cover of Edward Said’s memoir, “Out of Place”.

These three words described what Said felt was most denied to the Palestinians by the international media, the power to communicate their own history to a world hypnotised by a mythological Zionist narrative of an empty Palestine that would serve as a convenient homeland for Jews around the world who had endured centuries of racism, miraculously transformed by their labour from desert to a bountiful Eden.

In the course of articulating the Palestinian narrative in a series of classic books, Said wrote in his 1999 autobiography, Out of Place: A Memoir, that:

“I soon discovered that I would have to be on my guard against authority and that I needed to develop some mechanism or drive not to be discouraged by what I took to be efforts to silence or deflect me from being who I was, rather than becoming who they wanted me to be. In the process, I began a lifelong struggle and attempt to demystify the capriciousness and hypocrisy of a power whose authority depended absolutely on its ideological self-image as a moral agent, acting in good faith and with unimpeachable intentions.”

Despite numerous and bitter personal attacks — attempts to disingenuously portray him as a political radical opposed to peace with Israel — Said’s vision of the future of Israel/Palestine remained firmly and unshakably based on a belief that Palestinians and Israelis could live together in a democratic state that protected the rights of all of its inhabitants, both Jews and Arabs.

When I began work on Birzeit University’s original website in 1995, it was with Said’s phrase very clearly in mind that Birzeit’s web team set about creating our own realisation of the “permission to narrate”, creating a website with a diverse variety of news that communicated the universal values, strong commitment to academic freedom, and thriving culture on the university’s campus and in the surrounding Palestinian community.

On 25 September 1996, exactly seven years ago from Said’s passing away this morning after a long battle with cancer, Birzeit students set out to Jerusalem — frustrated with Israel’s unilateral control of the borders of the Palestinian capital and angry with then Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu’s authorisation of the opening of a tunnel along the base of Al-Haram Al-Shareef, site of the Al-Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock.

It was a symbolic journey, as various Israeli positions — military bases and checkpoints — lay between the nearby town of Ramallah and along the 20 minute drive to Jerusalem. At the edge of Ramallah, students got out of their buses and set ablaze discarded car tires — Palestine’s youth’s ubiquitous invitation to the Israeli occupation army to come stand before them.

With the main Oslo redeployments from Palestinian population areas having taken place 9 months previously and, despite severe periods of Israeli closure and continued land confiscation and the suicide bombs of Palestinian militant groups, Israeli troops and Palestinian police maintained a civil working relationship and many people on both sides still hoped that Oslo would limp its way to some kind of resolution to the century-old conflict over land.

On this day, however, Israeli troops responded to the standard out-of-range stone throwing and the occasional, similarly ineffectual Molotov cocktail with unusual ferocity, shocking even the hardened Palestinian veterans of the clashes of the first Intifada, who were present at the scene. Using a simultaneous combination of live ammunition and rubber-coated metal bullets, the Israeli troops that arrived to investigate the pyre wasted no time in loosing lethal munitions at the students and accompanying Ramallah residents who had joined their march along the way. In the words of several friends who independently witnessed the initial violence, the soldiers were cheering and giving each other high-fives when they shot someone. With the accuracy of their rifles, one friend described the scene as “one bullet, one person dead”.

Many of the Palestinian police present, hailing either from abroad or from less populated areas of the country, had never seen this level of violence directed at their own people. It took a while, during which several demonstrators were needlessly shot dead and ultimately only after Israeli troops invaded the autonomous area of Ramallah and shot a bystanding member of the Palestinian forces — before the Palestinian police retaliated. The murderous arrogance of the Israeli troops present had blinded them from considering that among the facts on the ground that changed with Oslo, was that — for once — they were committing these unnecessary crimes against humanity in front of trained Palestinians with guns.

Eleven Israelis died in the subsequent battle, which saw Israeli Cobra attack helicopters and heavy machine guns strafing the surrounding residential areas, and the later deployment of Israeli battle tanks on the hills. It was only after the key determining events of the first two hours that the international media arrived on the scene. Later, they predictably reported a reality utterly divergent from that witnessed by the 2,000 or so Palestinians and handful of internationals present.

Seven Palestinians were killed and 263 were injured in just a few hours on that day in Ramallah. I walked through Ramallah Hospital that night, looking at the grief-stricken faces of the sister and mother of Birzeit student Yasser Abdul Ghani, the first person to be killed that day. The hospital walls were smeared with blood that the medical staff were too busy to clean up, trying desperately as they were to stem the flow from the living. In the ICU, I gazed at Yasser, breathing only on life support. He and all others in the ICU were shot in the head or chest.

As media reports filled our televisions that night and newspapers hit the streets the next day quoting Israeli spokesman Dore Gold self-righteously whining that “the Palestinians were shooting at us with guns we gave them”, many of us who had witnessed the day’s events were boiling inside at the injustice, feeling powerless and vulnerable in light of our visceral lesson in the unaccountability of the Israeli army.

Marwan Tarazi, head of Birzeit’s Computer Center, burst through the door of my office. “We have to do something. What are you waiting for?” It finally dawned on me. Permission to narrate our side of the story lay at a nearby web address: www.birzeit.edu.

For the next four days, during this explosion which ultimately claimed 88 Palestinian and 16 Israeli lives, and resulted in several thousand injured Palestinians, a group of us worked day and night on the site. Like the Chinese pro-democracy students at Tiananmen, who used e-mail to alert the world to their government’s repression, local residents of a warzone used the web for the first time in history to tell their story. Our equipment was nominal, there were huge obstacles such as a commercial strike which closed all the photo developing studios in besieged Ramallah, preventing us for days from getting our film of the events processed, but we were committed, which turned out to be more than enough.

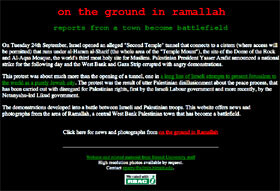

Homepage of “On the ground in Ramallah: Reports from a town become battlefield”.

Homepage of the “September 1996 Memorial” website.

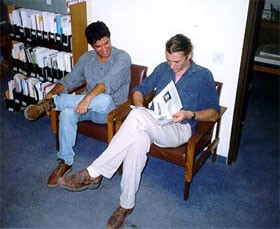

(L-R) Adam Hanieh and Nigel Parry working on the “September 1996 Memorial” website (Birzeit, September 1997).

Said was not respected by many in the Palestinian leadership. When I lived in Palestine, the corrupt and repressive Arafat banned the Arabic editions of two of Said’s books that were extremely critical of the Oslo process and the Palestinian leadership’s failures during the negotiations and implementation, sending security forces into Ramallah bookshops to physically confiscate copies. During a BBC World Service report, following an angry interview with Said, then Palestinian Authority Higher Education Minister Hanan Ashrawi came on to poo-poo the reports, her message and tone suggesting that Said was being a little excitable, that he was blowing the matter out of proportion. Later, a Palestinian ambassador to one of the European countries attempted to raise the matter directly with Arafat during a visit, while sitting with the leader in his car, noting that banning the book of the most prominent Palestinian academic in America might communicate a counter-productive message to the citizens of a country founded on the right to freedom of speech. “Fuck Edward Said!” shrieked Arafat in response, “Don’t talk to me about him again.”

In February 1997, Edward Said came to speak at Bethlehem University. I couldn’t attend the event but later a co-worker reported the content of his speech. During his talk, he mentioned a Palestinian activist in Chicago. “Each time I check my e-mail,” Said said to the packed-out crowd, “I find copies of e-mail sent by a young Palestinian to radio stations, TV reporters, and newspaper editors, commenting on their coverage of the Palestinian issue. In his effective, electronic way, this man, Ali Abunimah, is writing his own history every day.”

I wrote to Ali the following day, asking to be added to his e-mail list, which delivered as advertised and represented an incredible archive of criticism of the US media from a Palestinian perspective. Although we corresponded for two years after this, was not until February 1999 that I finally met Ali, while speaking at a conference at the University of Chicago, “The Uncertain State of Palestine: Futures of Research Conference”. At the same conference, I met Edward Said for the first time. Once he recognised my name, he had only kind words for the work we did at Birzeit but admitted that his knowledge of the web was minimal, preferring e-mail as an information tool.

“Did you know that a key component of the vision we had for the website and e-mail lists we create was your statement about giving Palestinians ‘permission to narrate’?” I asked.

Said looked genuinely surprised. He thought for a moment, smiled quietly to himself, and thanked me for telling him, inviting me to visit the next time I was in New York. Sadly, his illness, already advanced at the time, precluded this from happening.

Edward Said passed away this morning. He left behind a body of work and a lexicon which has empowered a generation of people concerned for the future of the Palestinians. He inspired projects such as The Electronic Intifada and many others, and inspired individuals like myself, the other founders of EI, and tens of thousands of people committed to reconciliation and justice around the world.

He will be greatly missed, often spoken of, and we will always be grateful for his time with us.

Nigel Parry is one of the co-founders of The Electronic Intifada.