The Electronic Intifada 16 September 2003

OF PLACELESS LAWS AND LAWLESS PLACES: DOES INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE HAVE A LOCAL ADDRESS?

Laurie King-Irani

Blinking sleep from my eyes, I peer at a small video screen embedded in the seat before me. The image of a small gray plane heading west on a bright green background comes into focus. We are somewhere above the cities of Munich and Nuremberg. Place names that resonate, venues of lawlessness and lawgiving; specific, intimate, and local to those who dwell there, but freighted with international and historical meanings for humanity since the end of World War II.

These German cities are deeply implicated in the journey I am undertaking and the research project I am pursuing: an ethnographic study of the processes and structures of international humanitarian law. I want to find out how the placeless principle of universal jurisdiction can be applied to lawless places like the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut, where a massacre claimed over a thousand innocent lives 21 years ago this week. I want to know if it is possible for international justice to have a local address.

This trip has taken me from the scene of the crime in Beirut to the final court of appeal for its victims in Brussels. It has also brought me up short with some sobering realizations.

Two years of reading abstract legal texts and attempting to apply their underlying principles to actual events has made me increasingly aware of the limitations of the law and the importance of power, place, and politics. Theories and ideals float, like our airplane, far above such complex realities. From on high, all seems clear, simple, and comprehensible. The lineaments of justice are as plain as the well-defined network of roads linking the German cities beneath us as we soar through the clear autumnal atmosphere.

But down there on the ground, in the actual places where crimes are committed and justice is attempted, positioning is everything. Where one is, or where one is placed, is as decisive for surviving a war crime as it is for successfully prosecuting its architects and perpetrators.

The principle of universal jurisdiction holds that place and positioning should not matter. In decreeing that some crimes are so heinous that they threaten all humankind, universal jurisdiction attempts to remove any safe havens for criminals by enabling citizens of one state to be tried for killing citizens of a second state in the courts of a third state. If all states were to honor the principle of universal jurisdiction by respecting and enforcing the ideals encoded in the Geneva Conventions and the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, a truly international and universal framework of justice would emerge. Impunity would soon be a problem of the past, and the motto “One yardstick for human rights!” would be a reality, not a dream.

But justice is not yet universal, in conception or in practice. Place and power do matter a lot, not only in the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity, but also in their prosecution. If nothing else, the complex melange of events, actions, interests, and groups that brought the survivors of a massacre in Beirut to a courtroom in Brussels showed us that much.

Trajectories

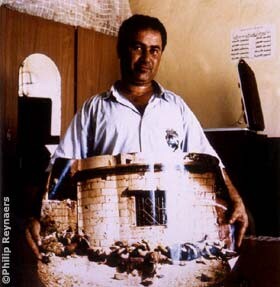

Hamad Mohamed Shamas holds a photograph taken in the aftermath of the massacres. He lay injured under the bodies on the left of the frame for a day and a night. (Philip Reynaers)

Hours later he crawls out from under the bloated corpses.

Decades later he becomes a plaintiff in a case lodged in Belgium to bring to trial the Lebanese killers and the Israeli commanders responsible for this crime against humanity.

In a courtroom on the third floor of the monumental Palais de Justice in Brussels, the Belgian Supreme Court rules, on 12 February 2003, that this survivor and 22 others have the right, under Belgium’s 1993 anti-atrocity legislation, to pursue a case charging high-ranking Israeli army officers and Lebanese militia leaders with responsibility for the massacre. The principle invoked — and on that day realized — by Belgium’s highest court is that of universal jurisdiction.

It is a legal landmark, indeed a potential turning point in the progressive evolution of international criminal prosecution. Abstract legal theories begin to take root in a particular, real world venue. Principles are emplaced, victims are empowered, and killers are alarmed by the ruling issued on the top floor of the Palais de Justice.

Envisioning Justice: The View from Brussels

And what a palace it is! The Belgian courthouse was the single largest public building in Europe in the 19th century, according to my city map and tour book: “Built between 1866 and 1883, this colossal work of arhitecture displays a curious Babylonian-Greco-Roman style and contains over 350 rooms.” Approaching the Palais de Justice for the first time from a nearby Metro station, I am awed by its massive size.

Luc Walleyn, George Irani, and Michael Verhaeghe outside the Palais de Justice in Brussels. (Laurie King-Irani)

Luc Walleyn, one of the lawyers for the Sabra and Shatila survivors, has instructed me to meet him and another Belgian lawyer for the plaintiffs, Michael Verhaeghe, at noon in the great hall of the Palais de Justice. For ten minutes, my husband George and I walk around and through the ground floor of the building, which houses police offices and military courts, scaling and descending short flights of well-worn marble staircases and passing door after door bearing the sign: Entree Interdit! Entrance forbidden.

The whole building is forbidding. After making a complete circuit of the ground floor, we realize that we are on the wrong level. A social worker emerging from an office crammed with filing cabinets tells us to take the elevator to the next floor. There we find even wider marble halls, even higher ceilings, and more doors forbidding our entry.

Finally, a tall, thin Black man approaches and asks us in French if we need help.

“Where is the great hall?” I ask.

“Please follow me,” he says, with a soft smile.

“Where are you from?” I ask him as our footsteps echo in the empty hallway.

“I am a lawyer here in Brussels,” he says.

“But where are you from originally?” my husband asks him in French.

“The Congo,” he answers.

“Oof! what a sad and horrendous disaster is unfolding there now!” George responds.

I cannot help thinking that a sad and horrendous disaster was unfolding there during the two decades it took for this building to be constructed. There is something perverse about a country spending a forture on a gargantuan hall of justice at home while committing atrocities abroad. And though Belgium cannot claim a unique status in this regard, its grim history of human rights abuses in colonial Africa led some detractors of the Belgian anti-atrocity law to deem the country a dubious address for the realization of the principles of international justice. If our guide shared this sense of irony, he kept it to himself, and said no more until we reached the great hall, a cavernous space that made New York City’s Grand Central Station seem cozy in comparison.

We enter and immediately see Luc and Michael sitting at a corner table talking to black-robed colleagues in hushed tones. As I approach them, I cannot stop craning my neck to see the distant ceiling of the great hall 105 meters above us. Michael and Luc greet us warmly. I have met Luc before at a conference at Princeton University, but Michael I know only through email communications and his appearance on the BBC television news program, “Hard Talk.”

“Quite a building, isn’t it?” Michael says to me. “They say that the architect went mad as soon as he finished it. I think the rulers at the time wanted to make it so large just to remind people of how small and insignificant they were before the law!” he added with a laugh as we headed for the exit.

“Notice the entrances to this building,” said Luc, as we paused at the top of a long and steep stairway. “Over there,” he continued, pointing toward a bright entryway on the opposite side of the great hall, “was the main entrance for the middle and upper classes of the previous century. It faces the nice part of town. The elite could just walk right in at ground level — their ground level — to this floor, which is for civil complaints. The lower floors were, and still are, for criminal complaints and now are also the location for social cases, juvenile delinquents, military cases, etc. Up there, on the next level, you have the Appeals Court, and above, on the very top level, is the Cour du Cassation, our Supreme Court, where we received the February ruling in our case.”

Turning to the long flight of stairs we were about to descend, Luc explained, “This was the entrance for the poor and the workers. It faces what was then the lower class part of town. Workers had to walk up a steep hill just to reach the foot of this building, and then they had to climb up all these many stairs to seek justice.”

“And by the time they got up here, they were probably too winded to ask for anything!” joked Michael, as we began our long descent to the exit.

The stairway leading from the main floor of the Brussels Palais de Justice to the former working class part of town. (Laurie King-Irani)

“This is just the sort of device we need, figuratively speaking, to help people gain access to universal justice!” I joked.

We all thought we had found such a device six months earlier.

Neither the Sabra and Shatila plaintiffs, their lawyers, nor most observers of judicial developments in Belgium had been optimistic about a Supreme Court ruling in the massacre survivors’ favor last February. The previous June, the Brussels Appeals Court had dashed the hopes of the Sabra and Shatila survivors, as well as the hopes of countless victims of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, by ruling that their case could not go forward since the accused “were not found on Belgian soil.” Place and placement mattered after all, it seemed. So much for the universal ambitions of universal jurisdiction.

All indications pointed to the triumph of impunity and the preservation of the perquisites of power when the lawyers for the Sabra and Shatila survivors, along with lawyers for Ariel Sharon, Amos Yaron and other Israelis charged with responsibility for the massacres, convened in the highest court in Belgium last February 12th. The plaintiffs, backed by a broad base of local and international human rights organizations, had lodged an appeal asking the Supreme Court to review and overturn the Appeals Court ruling on the grounds that it contradicted the meaning and intent of the universal jurisdiction law of 1993 and 1999.

That day had been an especially gray, cold, and rainy one here in Victoria, where I live. I awoke to a dispiriting telephone call from Chibli Mallat, the Lebanese lawyer representing the plaintiffs, during a lull in the Supreme Court hearings. “It is not going well,” he said ominously.

Two hours later, though, while unenthusiastically drafting a press release conceding the plaintiffs’ legal defeat but accentuating educational and moral triumphs, I received an urgent email from a friend in Beirut. She informed me that the Belgian Supreme Court had found in the Sabra and Shatila survivors’ favor, overturning the earlier Appeals Court ruling. The trial would go forward for Yaron and the other Israelis and Lebanese after all, but Sharon, enjoying temporary immunity as a sitting head of state, would still be untouchable — for the time being. The survivors of one of the most heinous massacres of the post-World War II era would get their day in court. At last, someone would finally be held legally accountable for the three days of murder, mayhem, torture, and rape that had claimed the lives of their loved ones.

Overjoyed, I called the lawyers in Brussels. After two exasperating years of hard work on this groundbreaking case, they were drinking champagne and giggling when I caught up with them. After sharing our delight and incredulity at this sudden, and very welcome, reversal in the fate of the case, we agreed that the people who deserved the most credit for the Supreme Court ruling were the plaintiffs themselves. They had taken an incredible risk by refusing to remain voiceless, faceless victims. I felt a profound sense of relief when I imagined how they would greet this news in the refugee camp.

Mapping Injustice: The View from Sabra and Shatila

“What did we expect, you ask? Nothing — just God’s mercy!” Mr. Alameh is doing his best to be a warm, gracious and generous host. I can tell, though, that his patience has grown thin with the likes of me. And I can hardly blame him. We sit in his living room above his computer repair shop in the camp, discussing the ups and downs of the case in Belgium since US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld had, as he himself phrased it, “taught Belgium a lesson” by threatening to move NATO headquarters to Poland unless the universal jurisdiction law was gutted. The newly elected Belgian Parliament had complied with this audacious US demand without hesitation.

Less than two months after this depressing development, I’ve come back to Beirut to pursue questions related to my research, but also to remind the plaintiffs that, despite the disappointments of the previous two months, they should never forget that they played a crucial role in shaping international legal history.

Mr. Alameh is unimpressed. He has a large and growing family to raise and a small business to run. Lawyers, journalists, and human rights activists have already taken up enough of his time, I sense. We are drinking chilled Pepsi-Cola with his teenage son and Mr. Mahmoud Abdullah Kallam, a son of the camps and the author of two books, one on the legendary Palestinian political cartoonist Naji Ali, and the other, recently published, on the massacre. Entitled “Sabra wa Shatila: Dhaakirat ad-Damm” (Sabra and Shatila: Memory of Blood. Beirut: Beisan Books, 2003), it is a painstakingly researched account of the massacre featuring detailed tables listing the name, age, gender, nationality and manner of death of each of the massacre’s victims, as well as the most complete list compiled to date of the many men and boys who were disappeared after the massacre.

New entrance to the mass gravesite in the camps. (Laurie King-Irani)

Mahmoud Kallam’s book contains some surprises: Only half of those killed were Palestinian refugees. Lebanese nationals, as well as Syrians, Egyptians, Pakistanis, Africans, Tunisians, Iranians, and others clinging to the margins of Beirut’s economy and society twenty-one years ago also perished in significant numbers during the massacre.

“Wayn makan, al-fuqaraa’ daiman ad-dahaaya.” (“Everywhere, the poor are always the victims”), Mahmoud observes as he shows me his data. Yet another sobering reminder that place and position, not just geographic, but also socioeconomic, matter during a massacre, as well as in its aftermath. Regardless of whether they were Palestinian refugees or holders of valid passports, the hundreds who died in these camps two decades ago were not advantageously positioned, sociologically speaking. Nor are they today.

Of the Palestinians killed during the massacre, Mahmoud draws attention to the large proportion of victims from the southwest quadrant of Shatila camp, Hyy Arsan. In his book he speculates that special attention was given by the killers to the residents of this particular neighborhood because young men from Hyy Arsan were responsible for taking Israeli athletes hostage at the 1972 Munich Olympics. If his hypothesis is correct, it implies very close coordination and collaboration between the Lebanese militiamen who did the killing and the Israeli Defense Force officers who helped them cross demarcation lines; fed, clothed, and armed them; and launched illumination flares into the night sky to facilitate their round-the-clock carnage.

Mahmoud further notes that other nearby refugee camps — Bourj al-Barajneh and Mar Elias, also located in and around Beirut — were not subjected to similar atrocities. His speculations point to an Israeli motive of revenge, and would have been very interesting to explore in a court of law.

The main thoroughfare of Shatila camp, dominated by a large garbage tip which grows and contracts throughout the day. (Laurie King-Irani)

Wandering through the oppressively hot and humid alleys of the camps with Mahmoud, stepping over puddles of sewage and walking past an expansive garbage tip, it seems absurd to be devoting so much time to pursuing justice for a 21-year-old massacre when the daily injustices that people suffer in this and other refugee camps in Lebanon have never ceased. If anything, conditions are worse now than they were two decades ago, given the demise of the Palestine Liberation Organization, Lebanon’s moribund economy, and UNRWA’s worsening financial straits. The violence that afflicts camp residents is not just the memory of rampaging Lebanese militiamen supplied, aided, abetted and directed by Israeli military commanders long ago, but also the structural violence of poverty, dispossession, inequality, and pollution that continues to pummel everyone trapped by circumstances in this marginalized corner of Beirut.

Yet the massacre still casts a long and chilly shadow in Sabra and Shatila two decades on. Bullet holes are still clearly visible in walls and door frames. As we pass people along our way, Mahmoud quietly informs me that “this man lost his mother,” “that woman lost her sons,” “this young woman lost her parents,” “that man tending the mass grave site,” now cleared of the garbage that desecrated it the last time I came here in 1997, “lost two dozen members of his immediate family.” A fractured and truncated kinship chart.

Later, lunching on shish tawook (grilled chicken sandwiches) washed down with more chilled Pepsi in Mahmoud’s crowded apartment, I notice that the main sitting room in which he, his small sons, wife, and I are eating is given over completely to books, newsclippings, magazines, and photographs related to the massacre. He gets up and moves a box or two out of the way to retrieve a well-worn manilla file folder containing death certificates of people who were previously thought to have died in the massacre. He proved they did not.

Mahmoud went house-to-house in the camps for a period of over two years to ascertain exactly who died, where, how, and when. The map of the massacre is seared into his memory, and at random moments during our walks he points to corners, shop entrances, intersections, and courtyards and tells me exactly whose body was found in each specific location. Just 45 minutes into our 10-hour tour through the camps, I am dazed by this constant barrage of macabre information.

Mahmoud’s relentless research has shown that fewer people died in the massacre than previously thought. He scoffs at claims that over 3000 were killed. “The total death toll was no more than 1,000, I am sure,” he asserts. “But 1,000 is no small number, and don’t forget that this does not include the number of people who were disappeared after the massacre, mostly from the sports stadium.” Various sources estimate the number of disappeared in the region of 1,000 people.

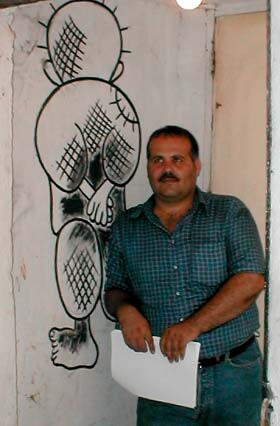

Mahmoud Abdullah Kallam, researcher and son of the camps, at the entrance to his family’s apartment in Shatila, before a drawing he made of “Handala,” the iconic representation of the long-suffering Palestinian refugee imortalised by the late cartoonist Naji Ali. (Laurie King-Irani)

“How old are children here by the time that they realize something awful happened in Shatila?” I asked Mahmoud as the boys run off, knocking their pop bottles to the floor in a rush to ride their tricycles back and forth in the short, narrow hallway between their father’s makeshift library and the sitting room where their four-month-old baby sister is trying to sleep.

Smiling sadly, Mahmoud answers, “As soon as they can walk or talk, they know about the massacre. Nearly every family lost someone, after all.”

Visiting Rituals in Shatila Camp

Visiting the homes of the plaintiffs, a common ritual unfolded: greetings were followed by offers of coffee, tea, or Pepsi. Brief comments were made in a spirit of bitterness or weary resignation about the case in Belgium, often accompanyied by reminders that only God, not some court in Europe, could deliver justice.

Then came the obligatory tour of the intimate imponderabilia of daily life — a wooden chest of drawers, a courtyard wall, a kitchen floor, the threshold to a mechanic’s shop — where bullets lodged, blood spilled, and bodies rotted 21 Septembers ago. Place matters in a massacre, especially when tangible evidence of murder and injustice is indelibly recorded on the homely surfaces of everyday existence.

One heavy-set man in his sixties, with kind eyes and a ready smile, waits until I am comfortably situated with a demitasse of coffee in one hand, my camera in the other before he approaches me, pulls up his shirt, and points to an area just to the left of his navel.

“Lammasini hon, sittnaa!” he quietly demands, “Touch me here, Ma’am!”

His wife and middle-aged daughters sit silently around me, their smiles and welcomes have suddenly faded. They look sad, though still dignified, their eyes focused on nothing in particular as I gingerly comply with their father’s request. Touching the damp flesh of his round white belly, I am shocked to feel the hard, spherical mass of a bullet trapped in his stomach muscles.

My eyes widen in alarm as I look up and meet his steady gaze. He steps back quietly, pulling his shirt down decisively.

“Na’am. Na’am. Shayfee?” (Yes. Yes. You see?), he sighs with pursed lips and pained eyes, nodding once to let me know that this is all he has to say about the massacre, the attempt at justice in Belgium, the quashing of that effort by Donald Rumsfeld, and my visit on this hot and humid day.

He then rolls up the cuff of his left trouser leg and encourages me to touch another bullet lodged in his calf. He not only dwells in the scene of the crime, the crime continues to dwell within him — literally.

As we finish our coffee, I play my perfunctory role in this visiting ritual by reminding them that the case in Belgium was a landmark legal event. The daughters shrug as if to say “Big deal!” Then the wife of the man with a bullet in his belly points to a place just two meters from my feet and relates how they found their neighbor shot dead there.

Father and daughter pose on the spot where they found their neighbors murdered in September 1982. (Laurie King-Irani)

Not your typical family snapshots.

As I leave, the father of the family, who was 20 when the massacre occurred, presses this chilling photo into my hand to take with me. I cannot refuse, and wonder if it will be best to take it and its horrific images away once and for all, out of reach of his small son trying to climb into my lap. The bullet holes in the courtyard wall are evidence enough of what happened here, aren’t they?

“Everyone has his or her Right!”

So where will international justice find a home in this particular locality, this intimate setting of mass graves, bullet-pocked walls, scarred adults, and children who know what a massacre is before they have learned how to read and write?

What does “universal” or “justice” mean here in the hot, malodorous, crowded specificity of Sabra and Shatila?

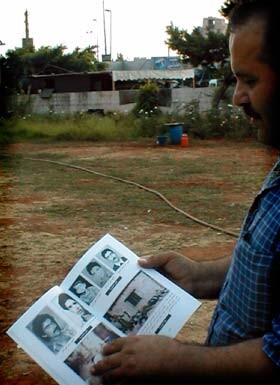

Mahmoud Abdallah Kallam displays portraits of murdered residents of Sabra and Shatila in his book. They are now buried in the mass grave behind him. Thanks to local and international efforts, the mass grave is now planted with roses and surrounded by young olive saplings. (Laurie King-Irani)

Nearly everyone I meet claims, in one turn of phrase or another, that rights must inevitably trump interests, and that no one’s interest — not even a state’s interest — can change this sacred fact. Decades of injustice and memories of a massacre have, oddly, not yet convinced the survivors of Sabra and Shatila otherwise.

As for the place of international humanitarian law and universal jurisdiction, perhaps Mr. Alameh, the first plaintiff I visited, summed it up the best.

“How important can these laws be, how strong are they, if America can change another country’s laws overnight? How can someone like Ariel Sharon make peace or talk about democracy when a court in Belgium said he is a war criminal? Who takes these laws seriously? Europe? America? Israel?”

But even though he cannot pin down the precise local address of universal justice, Mr. Alameh is sure it exists. He knows it by its absence; he knows it by what it could and should be, not just here, but everywhere.

His idea of the universal is that of universal rights, universal human rights, in which all of us share equally. His is not, though, an abstract “view from nowhere,” but rather, a view from a refugee camp where blood literally ran in the streets in September 1982.

“Look, power should be used for justice. Power should be used to ensure that each one has and preserves his or her right. If not, it’s the worst kind of terrorism there is.”

My theoretical musings are no match for his expertise in the abuse of power and the denial of justice, earned through a searing encounter with unspeakable terror 21 years ago. I don’t dare tell him that post-modernists would find his belief in universals naive.

Despite the disappointments and outrages they have suffered, it is clear that the survivors of the Sabra and Shatila massacre are not ready to give up their hope that justice will one day be as firmly rooted in their midst as are the bodies of their loved ones in the mass grave at the end of their street.

International law will not have a local address until it is given one, and that takes will, effort and power. It is not a task for a handful of massacre survivors in Beirut, a couple of lawyers in Brussels, or some cyberactivists in North America alone, but for all of us. Justice will only be universal when each of us gives it roots and nurtures it from the ground up, wherever we are, one locality at a time.

International law is your law. Know it. Use it. Hold abusers to it.

Laurie King-Irani, one of the co-founders of The Electronic Intifada, is North American Coordinator for the International Campaign for Justice for the Victims of Sabra and Shatila (www.indictsharon.net). She teaches social anthropology in British Columbia.