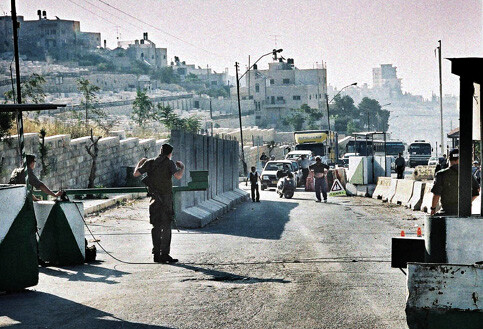

A checkpoint in the Palestinian West Bank. (Ronald de Hommel)

My father passed away last week.

I took Nawal, my two month old daughter, and attempted to go to Tel Aviv to attend the funeral and grieve with my family. Nablus, the city I live in, was besieged and completely sealed off. This has been the case for most of the last two years. Israeli soldiers threatened to shoot anyone approaching the checkpoint.

I had a letter from the hospital regarding a checkup that Nawal needed to do in Ramallah so we arrived at the Hawara check point in an ambulance. The ambulance stopped at the designated place. The soldiers did not shoot, thank God, but they also did not approach us. After about half an hour the driver decided to try to speak to them. He stepped out of the ambulance. Guns were pointed in his direction. He stepped back in. All we could do was wait.

All the while settler buses headed for the settlements that surround Nablus whisked past unchecked. Swallowing my outrage I thanked God that my baby was not suffering, that no one in the ambulance was in critical condition. The soldiers had no way of knowing that. But had they known it is likely it would have made no difference.

A year ago I was accompanying an ambulance through a checkpoint in Jenin. A young man with a bullet in his head was sprawled at the back of the ambulance, a doctor was pushing air into his lungs with a manual respirator. I sat next to the driver and said nothing while we waited and watched the patient’s condition deteriorate.

I know that being confrontational with soldiers can often aggravate a situation. I could not risk that happening. I calmed myself and waited for an opening. I offered the solider a cigarette. He accepted. I gave him another one for the other soldier, and then I ventured:

- “Is it really necessary that we wait so long? This guy is dying.”

The soldier looked embarrassed

- “We have to make sure he is not wanted.”

- “If you find out he’s wanted you can come and pick him up from the hospital. He’s not going to run away. He has a bullet in his head.”

- “I’ll see what I can do.”

That day we spent on hour and a half at the checkpoint. Time that assured that the young man’s brain damage was irreversible. The soldier, a young man himself, was just doing his job.

On the day of my father’s funeral we were “only” delayed for an hour. It was the third time Nawal made this journey since her birth. Despite the risk involved in getting in and out I came often because I knew my father was dying. I needed him to see his first grandchild, to tell him I loved him, to say goodbye. After the funeral we spent a week with our Israeli family.

My husband, who is Palestinian, is forbidden to enter the part of Israel/Palestine that was occupied in 1948. It was hard that he could not be with me. But I knew that I was privileged to be able to grieve with my family.

I kept thinking of my friend Amal, one of the most beautiful women I have ever seen, with huge hazel eyes and dark black hair. Her family was forced to leave Palestine for Jordan before she was born. Her husband, Abed, is from the West Bank. They have two beautiful children. If she leaves the West Bank, to see her family in Jordan, she will not be allowed back. Her parents have only seen their grandchildren in pictures. Her father was old and ill and she could not see him. He died and she could not be at his burial or comfort her mother.

Today, she refuses to accept that her father is dead. It is not death that she can’t deal with, for people living under occupation must live with death every day. It is that fact that she was forced to choose her husband and children over her parents that she can not live with. Her hair has suddenly began going white.

The policy of denying spouses of Palestinians residency is one of the many forms that ethnic cleansing takes here. It is a policy as old as the state of Israel but Sharon takes special pride in it. In his election campaign he boasted that he had stopped Palestinians from entering Israel (greater) by stopping family reunification completely. Amal will never see her father again. Many thousands of Palestinians share her fate.

Back home in Nablus Nawal and myself came back to our family and to the routine of waking up every night from the explosion of homes being destroyed or tanks thundering through the streets and shooting. In the meantime Nawal has learned to smile and, when she smiles, she shines like the sun.

Neta Golan is an Israeli peace activist and a co-founder of the International Solidarity Movement.