The Electronic Intifada 30 November 2010

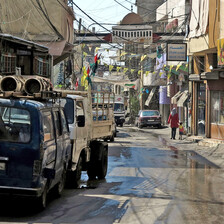

Nahr al-Bared, still in ruins years after the fighting ended.

More than three years after Nahr al-Bared refugee camp in the north of Lebanon was destroyed, its reconstruction is finally under way. However, the process runs at a slow pace and remains only partially funded as further political obstacles appear on the horizon. Meanwhile, the Lebanese army continues to maintain a tight grip on the camp’s residents and attempts to silence any criticism.

Anyone approaching the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp on the highway connecting the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli to the Syrian border can see it — the first row of houses are four stories high. After three years of tough negotiations, countless obstacles and various delays, reconstruction is actually underway.

The master plan for the reconstruction of the camp was prepared in early 2008, only half a year after a 15-week battle between the Lebanese army and the non-Palestinian militant group Fatah al-Islam that left the camp totally devastated. The camp’s 30,000 residents were displaced, some for the third or fourth time since they were expelled from Palestine by Zionist militias in 1948 — what Palestinians call the Nakba.

Delayed reconstruction

Reconstruction effectively kicked off in November 2009. “There were a number of problems getting the whole thing started, demining in the first place,” said Charlie Higgins, Project Manager for the Reconstruction of Nahr al-Bared with the UN agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA). “When we started the backfilling there, the whole archaeological controversy and the related court injunction came up, effectively delaying the process for another five months,” he explained, referring to a politically-motivated attempt by Free Patriotic Movement leader Michel Aoun in 2009 to stop reconstruction of the camp because of evidence of archaeological remains.

For practical reasons, the project was split into eight stages or “packages”. The first stage — consisting of 149 buildings which house 423 of more than 5,000 displaced families — is approaching completion, however with significant delay. “We expect to be able to hand over a number of apartments probably in early 2011,” Higgins said.

The main reasons for the delay are attributed to the construction company which subcontracted major parts of the work, adding additional layers of management that increased costs while reducing control of progress on site. Higgins said that without UNRWA’s constant pressure and threats of penalties, less would have been done.

Most workers on the construction site are Syrians and Palestinians. One of them is “M,” a resident of the Nahr al-Bared camp in his twenties. Almost three years ago, his family was permitted to return to the outskirts of the devastated camp. There, they’ve been living in steel containers, which residents call the “barracks,” awaiting the reconstruction of their homes. “When we moved into the temporary housing, we didn’t expect to be staying in there for such a long time,” M said. “Living in the barracks has always been very difficult.”

During the last years, unemployment, harsh living conditions, poverty, desperation and constant psychological stress have diminished M’s initial hope for a quick return. Now, he’s happy to have an income at least, although his job isn’t safe. By working on the first stage, M is witnessing the slow pace of reconstruction. “I have no illusions,” he admitted, “it will take a few more years until my family and I will be able to return home.”

According to Higgins, UNRWA’s efforts to get the contractor to employ Palestinians from the camp caused problems. “Workers need special permits to access the site, and to obtain them they may have to report to the headquarters of the Lebanese Armed Forces in al-Qubbe for investigation. This discourages some people from applying for jobs, and the contractor has cited the time taken as a factor beyond their control that delays the work.”

Recently, backfilling work has started in parts of the area designated for stage two of the reconstruction. UNRWA anticipates its completion by autumn 2011. The agency is determined to avoid the delays it encountered in the first sector. In addition, three schools at UNRWA’s coastal compound are under construction and will be ready by next summer.

One of the major obstacles on the way to rebuilding the camp is the lack of funding. “We have $120 million, but we still need another $209 million,” said Higgins. Yet he remains optimistic that once the initial group of residents have moved into the first homes, donors will be encouraged to make further pledges. According to Higgins, “We’d have a strong case to say: we can prove it can be done. Now, what about the other 16,000 or 17,000 people we need to give back their homes?”

“The adjacent area”

Even more doubtful is the reconstruction of the immediate surroundings of the camp, which have been termed by UNRWA and the Lebanese government as the “adjacent area.” The area forms a ring around the official boundaries of the camp and was inhabited by almost 10,000 Palestinian refugees. As the original camp became increasingly densely populated over time, houses grew in height and width, leaving hardly any place for streets and alleys. Consequently, many residents resettled in the camp’s adjacent area.

Many homes in the surrounding area were either totally or partially destroyed in the war. The Vienna document of June 2008, outlining the Lebanese government’s recovery and reconstruction strategy for the camp and the nearby municipalities, charged a Tripartite Committee consisting of the government itself, UNRWA and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) with the development of a full implementation plan for recovery and reconstruction in the adjacent area.

However, the committee was never formed. UNRWA denies having a role in the reconstruction of the adjacent area, limiting its responsibility to the camp’s original site. Palestinian refugees living in the adjacent area are entitled to benefit from UNRWA’s services as their registration with the agency is valid regardless of where they reside. UNRWA stresses its current infrastructure and efforts in the adjacent area have to be considered as temporary and within the agency’s emergency response to the displacement of the residents.

Speaking on behalf of the PLO, Marwan Abdelal said bluntly: “In political terms, there’s no partnership.”

The Lebanese government has not taken part in any participatory mechanism, nor has it presented a plan for the adjacent area or undertaken any significant recovery efforts yet. However, it has compensated residents of the third-ring or outlying area of the camp for war-related losses.

Problems in the adjacent area have deep roots. Decades ago, zoning laws were violated when Lebanese private land plots were subdivided in order to sell them to Palestinians. This illegal practice is common to many Lebanese villages and poor neighborhoods. The Lebanese government and its appointed official responsible for the reconstruction of the camp, Sateh Arnaout, have made it clear that the zoning laws will be strictly followed. However, if the reconstruction in the adjacent area has to happen according to Lebanon’s zoning laws, half of the existing buildings would actually have to be demolished.

In addition, approximately 90 percent of the refugees’ land purchases before 2001 were never fully entered in the Lebanese land registry and remain listed under the name of the former Lebanese owners. Even worse, since 2001, Palestinians are forbidden to own or inherit property. Legal reconstruction and registration is therefore impossible.

“Palestinian residents in the adjacent area whose houses were totally destroyed are the first victims of this policy, as the government still blocks their reconstruction,” said Abdelal. “At least we’ve successfully intervened concerning the rehabilitation of the partially demolished homes.”

At a recent conference at the American University of Beirut, Rana Hassan, a Master of Urban Policy and Planning candidate at the university’s Architecture and Design Department, stated that a different approach is needed by the Lebanese government. She cited precedents such as the reconstruction in south Lebanon’s villages and Beirut’s southern Dahiya suburb after the destructive Israeli invasion of Lebanon in July 2006. Nevertheless, the Lebanese government’s Recovery and Reconstruction Cell (RRC) seems to stubbornly insist on strict adherence to zoning laws when it comes to Nahr al-Bared.

No freedom of movement

Three years after the end of hostilities in Nahr al-Bared, the refugee camp and the adjacent area remain a military zone. Checkpoints manned by the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), a rigid permit system and recently reenforced barbed wire restrict access to the camp. For years, residents have protested this access regime without success. UNRWA’s Higgins said that the agency believes the return of the first residents will be a change on the ground that could lead to more positive developments on access in general.

However, Abdelal argued that “The war has ended three years ago, so there’s no need for the army’s presence anymore.”

Nor has the army eased its entry restrictions in response to the construction. “We haven’t seen any significant change on access over recent months,” Higgins acknowledged. Although Lebanese citizens can enter without special permits, they’re subjected to questioning at the checkpoints. The refugees’ permits are valid longer than before, but visitors or nongovernmental organization personnel face even more difficulties to obtaining entry permits.

Within the camp, hardly anyone dares to speak up against the LAF. “Freedom of speech is massively restricted,” said Ismael Sheikh Hassan, an architect and urban planner who has worked with the community-based Nahr al-Bared Reconstruction Commission for several years. “Anyone in Nahr al-Bared can be arrested by the military intelligence and be held without access to family, lawyers, etc.,” he explained. He says there are many cases that were never publicized, partly due to the fact that hardly any journalists manage to obtain army permits to access the camps.

Sheikh Hassan is convinced that under military siege, the camp’s economy will never be able to function. Its residents are now almost completely dependent on international assistance.

“More importantly,” Hassan said, “under the army’s restrictions, there is no chance for reestablishing relations between the camp and the surrounding communities to return to a level of normality.”

Even if some restrictions were relaxed, Hassan stated, any prolongation of the militarization and siege of the camp might have irreversible consequences. “Economies and consumer patterns might shift and Nahr al-Bared might never be able to return to its previous economic role in the region,” he said.

Silencing the critics

In mid-August, Sheikh Hassan was arrested at a checkpoint when entering Nahr al-Bared. He was held for three days. His interrogation revealed that he was apparently detained because of an article he wrote for the Lebanese newspaper as-Safir describing the conditions in Nahr al-Bared. After his release, it remains unclear whether he’ll have to appear in front of a court.

“The situation is gray,” Hassan explained. “There is no official court date. But also, there’s no acquittal that I’m innocent.”

Over the past few months, the LAF have been conducting a campaign of intimidation against its critics. Recently, the director of a nongovernmental organization operating in the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp had his entry permit revoked after criticizing the LAF. Also, since July, the LAF refused to issue permits to the staff of another organization, the Palestinian Human Rights Organization (PHRO).

Ghassan Abdallah, the PHRO’s director, is an outspoken opponent of the LAF’s permit regime and intimidation practices in Nahr al-Bared. The PHRO recently released a report examining restrictions on freedom of movement in the camp (Lebanese Restrictions on Freedom of Movement [PDF]). On 5 October, Abdallah was invited by Lebanese military intelligence to have a cup of coffee at the al-Qubbe army base. When he arrived at the base four days later, Abdallah was interrogated for three hours and even threatened with torture. In particular, Abdallah was questioned about a dialogue meeting on the LAF’s access policy to Nahr al-Bared that he had co-organized.

“The security zone,” Abdallah said, “is neither legal, nor humane. There’s no excuse for it after three years.” However, army intelligence doesn’t accept this kind of criticism, he said. He expressed his outrage that after an official meeting where the Lebanese-Palestinian Dialogue Committee and the LAF were represented, he was interrogated by military intelligence.

On 16 October, Lebanese activist and blogger Farah Kobeissi was arrested at the al-Abdi checkpoint at the northern entrance to Nahr al-Bared and interrogated for 14 hours after protesting against the army which denied her entry to the camp. During the protest, she held a banner stating: “No to the humiliating permits in Nahr al-Bared Camp.”

The LAF maintains full authority over the camp, which it is not reluctant to display. Three months ago, it unveiled a monument dedicated to the fallen Lebanese soldiers of the Nahr al-Bared battle at the northern entrance to the camp.

Construction worker “M” is upset that the monument doesn’t mention the fifty Palestinian civilians who were killed in the conflict. “This is the wrong place for this statue,” he said. “They shouldn’t have put it right in front of our camp.”

Palestinians a “special category”

Nahr al-Bared isn’t just a Palestinian refugee camp that was destroyed and has to be rebuilt. It showcases the difficult situation of the more than 400,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, who have faced massive discrimination for more than sixty years.

At the American University of Beirut, associate professor Sari Hanafi closely observes Palestinian-Lebanese relations. He understands Lebanon’s desire to have full control over its territory and inhabitants. “However,” he said, “when you talk about sovereignty, you have to define who’s subjected to it.” For decades, Lebanon’s Palestinians have been treated as a special category.

Hanafi stressed that Lebanon finally has to clarify the Palestinians’ status, bear the consequences and abolish their discrimination. “If it considers them foreigners,” he said, “they need to be given the possibility to work, own property and join the professional syndicates. If it considers them refugees, they have to be given all their refugee rights according to the 1951 Refugee Convention.”

The debate on the Palestinians’ legal situation is directly connected to the Nahr al-Bared camp, where the Lebanese police have established a center. According to the Vienna document, “community policing” is to be implemented in the camp. The project is funded with $5 million by the United States. On the ground however, the LAF and the military intelligence remain in charge. Many residents compare their rule to the former Deuxieme Bureau, the military intelligence service which had harsly controlled the Palestinian refugee camps the 1950s and ’60s.

Hanafi considers the police deployment as highly problematic, as long as the inhabitants’ status isn’t clearly defined. “I see the police stationed in Nahr al-Bared as a counterinsurgency police, not a community police,” he said. “There’s no agreement with the local popular committee. On the contrary — the first thing the police did was outlaw all the Palestinian structures there.”

“In any case: If any Lebanese police in Nahr al-Bared were to implement the current discriminatory law, nearly anyone in the camp would have to be arrested — for owning property, for working in forbidden professions, etc,” Hanafi added.

Hanafi said Palestinians have legitimate reason to fear the police. “They are right in saying: ‘Before you bring the police, let us know if we can have shops, associations and a popular committee.’”

Earlier this month, the UN Human Rights Council reviewed the human rights situation in Lebanon. Many member states accused Lebanon of discriminating against the Palestinian refugees. Their recommendations focused on freedom of movement, property rights and access to all professions — which were rejected by the Lebanese government. Similarly, Norway’s specific request to allow free entry into and exit from the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp was also rejected by the Lebanese delegation.

The Nahr al-Bared refugee camp highlights every aspect of the problematic relationship between Lebanon and the Palestinian refugees within its borders. However, the Lebanese government would be better served by viewing the camp as a chance to radically change the traditionally conflict-ridden relationship in which Palestinians are only viewed as a “security issue.” This could be achieved by respecting Palestinians’ civil rights and seriously engaging in the reconstruction of the camp.

All images by Ray Smith.

Ray Smith is a freelance journalist and activist with the anarchist media collective a-films, which has documented developments in the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp for the past three years.