The Electronic Intifada al-Maghazi refugee camp 28 October 2010

Amna Hammad, or Umm Jihad

“In 1967, when Israel occupied the Gaza Strip, my husband left Gaza along with thousands of others who fled the Israeli invasion. He left me with three sons, Jihad, then aged four, Nihad, then two and Adnan, a six-month-old baby. So I had to take responsibility for all of them, being a mother and father at the same,” Umm Jihad explained.

To take care of her children, Umm Jihad had to start working, but she faced restrictive traditions and customs. Her brother objected to her working, but to get by for the sake of her children, she defied his wishes and the norms of a very conservative society.

“The situation at that time was so difficult not only for me — a single mother of three — but also for the entire community around me. In 1948, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians like myself were displaced by the Israeli troops from our original towns and villages like al-Maghar, from where I am from.”

Al-Maghar, whose recorded history dates back to at least eighth century, was a village of 1,700 persons near the city of Ramle in what is now inside Israel. It was attacked and its residents expelled by the Givati Brigade of the Haganah Zionist militia on 15 May 1948, and within weeks ordered destroyed by the Jewish National Fund, as Walid Khalidi’s essential reference book All That Remains records.

From 1948 when she first became a refugee until the Israeli occupation of Gaza in 1967, “We had very harsh conditions, depending entirely on UN-provided food aid. So I had to defy the customs that would bring nothing to my three sons and my mother-in-law [whom I also cared for],” Hammad recalled with pride.

Hammad began her working life right after her husband left for Egypt. “At that time there wasn’t much work, all very simple jobs. Sometimes I used to work harvesting citrus. I kept moving from place to place for about three years. In 1970, I began working inside Israel, mainly in factories for citrus juice or food canning.”

Umm Jihad recalls how tough it was when she used to work inside the “green line” or what is now Israel: “I would get up at 3am to start my day. I used to prepare the food and wash the clothes before leaving for work. I had no chance to hug my children like any other mother, to feel the warmth of family life.”

“During the early years of my work inside the green line I don’t remember that I prepared my sons for school, as as many other women normally did,” Umm Jihad recalled as her grown sons sat at her side. “That was enough for me to feel the bitterness of such a life, while their father was away from them, while the community was too poor to help and while the society’s traditions restricted the life of a woman in my situation.”

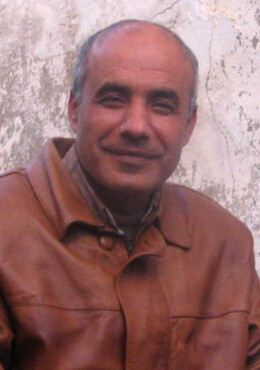

Jihad Abu Saqer

In 1980, Jihad headed for Egypt to study English with the money his mother had saved through her work in Israeli factories. Now Jihad is a well-known person in the al-Maghazi community who teaches English to secondary school students.

“I have learned how to make my way in life from my tolerant and hardworking mother,” Jihad said. “May God bless her and make her the happiest mother in town.”

Umm Jihad’s son Nihad, who lives in the same house as his mother, remembers the hardships his mother endured, working in the absence of their father.

“During my high school education, I recall that I used to be very embarrassed while speaking to my classmates. Once I argued with my colleagues by saying that no one is suffering like myself,” said Nihad while putting his hand on his mother’s shoulder.

Nihad said that his mother would always boast of his and his brothers’ high marks at school and show off their awards to their neighbors. But in his eyes this only made things more difficult.

“In the final high-school exam, I didn’t answer any questions, and instead I filled in the answer sheets with the lyrics of songs, just to make myself fail and force my mother to stop working so I would work instead of her,” Nihad recalled. “You cannot imagine — our society is that hard and can hardly accept you being sponsored by a woman, even if she is your mother.”

Adnan, Umm Jihad’s youngest, said that after his father returned to Gaza in 1995, right after the Oslo accords, he found it hard to utter the word “dad.”

“Only last year could I call him my father; I have never felt that I have a father,” Adnan said. “How could I call him ‘dad’ while was never around over the past years?” Adnan said that his father now also has four daughters and a son with another wife.

But despite such feelings, Adnan said his mother always told him and his brothers, “At the end of the day he is your father.”

For Nihad as well, the return of his father was fraught. “For the first time ever since he returned to Gaza, to my surprise I took some money my father held in front of us while visiting us at this home. I don’t know what happened, maybe I just felt I needed to take rather than give. I had been deprived of taking money from a father like other children on this earth,” Nihad said, a smile on his face.

However, Umm Jihad reminded, “I have always been keen not to deprive my sons of anything they need … Thank God, they do their best to make me the happiest mother in the neighborhood, may God be satisfied with them.”

All photos by Rami Almeghari.

Rami Almeghari is a journalist and university lecturer based in the Gaza Strip.