The Electronic Intifada 2 August 2010

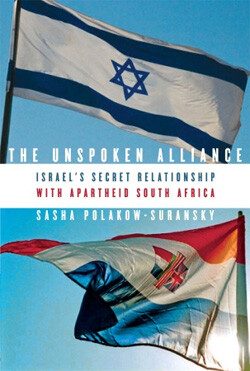

The Unspoken Alliance offers some new revelations on the details of the Israel-South Africa nuclear relationship. In so doing it is a welcome addition existing works, including Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi’s The Israel Connection: Who Israel Arms and Why (1987) and other (often less critical) investigations of Israel’s strategic relations during a period of growing isolation (Stewart Reisner’s The Israeli Arms Industry: Foreign Policy, Arms Transfers and Military Doctrine of a Small State (1989), Bishara Bahbah’s Israel and Latin America: The Military Connection (1986), and Aaron S. Klieman’s Israel’s Global Reach: Arms Sales as Diplomacy (1985). Although The Unspoken Alliance has garnered a great deal of attention, the Israel-South Africa alliance was very well spoken of by officials from both nations as well as critics, analysts and statespersons too numerous to count, just not so recently.

Indeed, The Unspoken Alliance shares a great deal with Beit-Hallahmi’s work, even beginning with the exact same incident, the April 1976 visit to the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial by South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster. Where The Unspoken Alliance departs from works from the 1980s by including in-depth examinations of Afrikaner apartheid, the racial position of Jews in South Africa, the depth of the nuclear relationship and the initial reservations of Israeli officials in supporting apartheid — all eventually overcome. While most of its content has been published in a less detailed manner previously in either news reports or books, The Unspoken Alliance makes a substantial contribution to the historical literature through its use of South African archival material augmented by dozens of detailed interviews with South African and Israeli participants and policy-makers during the period in question.

From the visit of Vorster — an active Nazi supporter during the Second World War — Polakow-Suransky traces the evolution of Israel’s relationships on the African continent, portraying it much as Israel saw itself: a newly independent nation free of European colonialism. In doing so the author makes a few suspect claims, writing: “Prior to 1967, Israel was a celebrated cause of the left. The nascent Jewish state, since its creation amid the ashes of Auschwitz, was widely recognized as a triumph for justice and human rights” (p. 4). While it’s true that Israel was initially embraced, especially by European leftists, after the 1956 Suez invasion with Britain and France, it was increasingly viewed with suspicion as an outpost of European colonialism in most of Asia and Africa, especially by the countries of the non-aligned movement (NAM). The Unspoken Alliance suffers initially by contextualizing the developing Israel-South Africa relationship through a decidedly Western lens; yet this point of view still makes for fascinating reading.

The “newly-free” self-image of the Israeli state appeared to be more in line with post-colonial African states than the European home of Zionism. Polakow-Suransky documents the idealistic solidarity expressed with Ghana, Senegal, Cote D’Ivoire and other nations by the socialist Ashkenazi leadership. Israel during this period publicly condemned South African apartheid as antithetical to both basic human rights and Jewish values. Polakow-Suransky quotes former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir’s autobiography as emblematic of the mindset of Israel as a proud nation of the Third World: “Independence had come to us, as it was coming to Africa, not served up on a silver platter but after years of struggle. Like them, we had shaken off foreign rule; like them we had learn for ourselves how to reclaim the land, how to increase the yields of our crops, how to irrigate, how to raise poultry, how to live together and how to defend ourselves” (p. 28). David Ben Gurion noted that even if South African Jews had been at risk — the book makes clear they were not — Israel could not have supported apartheid at the UN; “A Jew can’t be for discrimination,” he told Knesset (p. 31).

The Unspoken Alliance does not adequately emphasize the strong strains of pragmatism that pulled Israel much more strongly into the West’s camp. Polakow-Suransky acknowledges the tension between Israel’s patron-client status with France and the postcolonial self-image in a telling passage: “The Algerian representative rose to demand how Israel could justify its ties with ‘a government that is fighting a ruthless and brutal war against my people … and that is the primary foe of the self-determination of the African people?’” But he rather dismisses it, continuing: “The chain-smoking Meir paused, lit a cigarette, and replied coolly: ‘Our neighbors … are out to destroy us with arms they receive free of charge from the Soviet Union. … The one and only country in the world that is ready … to sell us some of the arms we need in order to protect ourselves is France.’ She then put the question to the audience: ’ If you were in that position, what would you do?’” (p. 27). In such passages Polakow-Suransky seems to posit relations with the apartheid regime in South Africa as mutually exclusive with its other goals, stating that “Israel needed allies and rather than turning to the racists in Pretoria, Ben-Gurion and Meir looked to the emerging nations of the Third World” (p. 21).

The tension between Israel and the rest of the Third World continued to grow. Israel’s aid to Portugal during the 1960s in the latter’s effort to maintain control over Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau, opposing the 1959 UN votes for Cameroonian elections and independence for all African colonies, abstaining on the 1960 UN votes for Tanganyikan, Rwandan and Burundian independence and voting against Algerian UN membership in 1962, all contrast with the narrative of enlightened foreign policy The Unspoken Alliance presents (see Beit-Hallahmi, p. 44-45 for example). These actions were actually more consistent with Israel’s “Alliance of the Periphery,” a fairly successful project to establish alliances with prominent nations outside the Arab world, especially Iran, Ethiopia and Turkey, all highly authoritarian and right-wing at the time. This is not to say Israel’s solidarity with newly-independent African nations was insincere. Polakow-Suransky documents this thoroughly enough to clearly show that what was in place was a double-standard.

Polakow-Suransky argues that the June 1967 War was the essential turning point in both Israel’s position in the (then-developing) broader Third World consensus on Palestine and Israel’s full embrace of the South African alliance (as well as the trend toward its own more formal apartheid system). Though Foreign Minister Abba Eban and his predecessor Golda Meir both had deep ideological opposition to Afrikaner apartheid, Israel had established formal relations with South Africa in 1949, the South African military and police were already using the Israeli Galil and Uzis weapons in 1955, South African police were undergoing security training in Israel, and in 1962 Israel sold South Africa 32 Centurion tanks and purchased yellowcake uranium (some of which Polakow-Suransky notes). These events and other exchanges, including the budding commercial relationship, laid the groundwork for the ideological and strategic alliance and in this sense, 1967 was less a turning point than an acceleration. Indeed, the “minimal” mid-1960s “diplomatic contact between Israel and South Africa” the author points to (p. 45) seems contradicted by “formal bilateral agreement on [nuclear] safeguards” signed in 1965 (p. 42).

Nevertheless it’s true that during this period the Israel-South Africa relationship developed into a full-blown strategic alliance — matched only by Israel’s relationship with the US — and Israel’s relations with other African countries deteriorated with only South Africa, Malawi, Lesotho and Swaziland maintaining relations by 1977. In the chapter “The Rise of Realpolitik” Polakow-Suransky documents the transition. South Africa had long wanted more open relations with Jerusalem, but it wasn’t until “Israel’s strategic thinking — colored by Cold War politics and new threats to its security — changed dramatically in the 1970s” that Israel stepped into the pool with both feet. “The young state had become an occupying power, the Soviet stance toward Israel had hardened, and the old Labor Zionists who were born in Eastern Europe and immigrated to Palestine in the early 1900s were giving way to a younger generation with an entirely different worldview.” (p. 63) Suransky-Polakow quotes PM Vorster in a New York Times article stating: “We view Israel’s position and problems with understanding and sympathy. Like us they have to deal with terrorist infiltration across the border; and like us they have enemies bent on their destruction” (p. 65).

This ideological sympathy was matched by the military relationship. During the 1970s and 1980s, if the Israeli arms industry made it, South Africa bought it. Suransky-Polakow details South Africa’s deteriorating relationships with essentially every country but Israel, including its difficulty in sourcing weapons. The Israeli arms lifeline, which included everything from Jericho missiles to military training to radar systems and aircrafts, helped sustain South Africa’s wars against Mozambique and Angola and its occupation of Namibia. The publicity the book has received thus far is largely not about these sales, but about the transfer of nuclear weapons technology from Israel to South Africa.

Documentation of these sales in The Unspoken Alliance has drawn wide condemnation from Israel. President Shimon Peres denied Polakow-Suransky’s voluminous evidence, saying “there exists no basis in reality for the claims.” Deputy Prime Minister Dan Meridor, Professor Avner Cohen, columnist Anshei Pfeiffer and former Deputy Foreign Minister Yossi Beilin and others have all come to the defense of Israel’s nuclear honor. In the chapter “The Atomic Bond,” Suransky-Polakow lays the basis for both nations’ quests for nuclear weapons and the resulting collaboration is repeated throughout the book and throughout the duration of the alliance. While the reactions to The Unspoken Alliance have over-focused on this aspect, the book itself contains a more damning portrait of the broader relationship with active Israeli collaboration with the implementation of apartheid policies. Indeed, in the epilogue, Polakow-Suransky discusses the development of Israel’s own apartheid system.

It is here again that the use of 1967 as a fundamental turning point is somewhat problematic. It is true that the trajectory of Israeli policy changed in 1967, prior to which it had begun to act more like a state and less like a piece of the Zionist political movement (an early and still useful analysis of this comes from Amos Elon’s terrific The Israelis: Founders and Sons, 1971). In its foreign policy, Israel was already losing friends internationally and associating itself with right-wing tyrannical regimes across the globe. In this the post-1967 trend seems less like a new direction and more like a crystallization of the pragmatic policies of years previous. The Unspoken Alliance does not lack for detailed and scathing analysis about the Israel-South Africa analysis, it’s noticeable failings being merely contextual. The framing of Israel’s foreign policy as having once been principled, as opposed to having righteous elements, is problematic as the lack of broader context for the 1970s-’80s with both Israel and South Africa also supporting the regimes in Taiwan, South Korea, Argentina, the Shah’s Iran and others.

The other notable misstep of the book is Polakow-Suransky somewhat neglects the role of the US in the Israeli-South African exchanges. He details the development of the military alliance and does include the US in the narrative. A great deal of time is spent on how Israel concealed parts of its South African dealings from the US. This is undoubtedly true but most US client states at the time offered their patron a facade of plausible deniability. A critic of The Unspoken Alliance, Deputy Prime Minister Dan Meridor stated in 1981 about US policies: “We are going to say to the Americans, don’t compete with us in South Africa, don’t compete with us in the Caribbean or in other countries where you couldn’t directly do it. Let us do it” (Montreal Gazette, 5 September 1981). Apartheid South Africa, the Central American dictatorships and others were US allies in the Cold War and Israel’s exchanges with South Africa took place in this context. There are numerous examples of Israel acting on behalf of the US, most prominently with the Contras in Nicaragua in the 1980s, and given apartheid South Africa as a strategic Cold War ally of the US, the Israel-South Africa alliance is best understood as a US-Israel-South Africa axis. To what degree South African arms deals were done in the US interest or the Israeli interest is in question, but not the general thrust of the relationship. Eventually the South African relationship became politically untenable in Israel, shortly after it did in the US. Had the US cut off all support to the apartheid regime it’s almost certain that Israel would have as well, which speaks to the importance of the US in the Israeli-South African relationship.

What makes The Unspoken Alliance “unspoken” today is more the — largely Western — short-term memory that has an Oslo-era image of Israel in mind. Dozens of nations established ties with Israel after the start of the Oslo process and this, combined with the fall of apartheid in South Africa, led to the notion that both nations were abandoning their oppressive regimes. In its own way, The Unspoken Alliance is a return to literature of the earlier anti-apartheid era. If this is indeed the case, and with the current movement against Israeli apartheid producing vibrations large enough to be reflected in popular and scholarly works, it may well portend the coming end of yet another apartheid state.

Jimmy Johnson is a mechanic based in Detroit. He can be reached at johnson [dot] jimmy [at] gmail [dot] com.

Related Links