The Electronic Intifada 26 April 2010

Said was primarily a historian of ideas. More precisely, he was interested in “discourse,” the stories a society tells itself and by which it (mis)understands itself and others. His landmark book Orientalism examined the Western constructs of Islam and the “East,” as depicted by Gustave Flaubert and Ernest Renan, Bernard Lewis and CNN. Said’s multi-disciplinary approach, his treatment of poetry, news coverage and colonial administration documents as aspects of one cultural continuum, was hugely influential in academia, helping to spawn a host of “postcolonial” studies. Said’s Culture and Imperialism expanded the focus to include Western depictions of India, Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America, and the literary and political “replies” of the colonized.

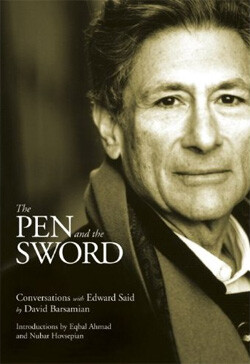

Edward Said died in 2003. His friend Eqbal Ahmad — who wrote one of the excellent introductions to The Pen and the Sword, published this year by Haymarket Books — died in 1999. This book — a collection of five interviews with Said conducted between 1987 and 1994 by David Barsamian, the founder of Alternative Radio — serves partly as a memoriam for Said himself and for the generation he represented.

Two of the interviews concentrate on the dual role of culture in propping up and deconstructing colonial oppression. There are illuminating discussions of Camus, V. S. Naipaul, Joseph Conrad and Mahmoud Darwish, amongst others. Said proclaims the importance of “writing back” to imperialism, and most specifically to Zionism by “telling the story of Palestine.” He examines the obstructions to the airing of this story in the West, as well as the contradictions of Zionism’s “dominant narrative.” Said understood that anti-Palestinian propaganda was not merely a pragmatic tactic for Zionism but central to its epistemology and sense of itself. Significantly, he exposed the connections between Western anti-Arab racism and European anti-Semitism.

Two interviews focus on Said’s criticisms of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). According to Said, the leadership lost touch with its people after Israel drove it out of Lebanon (and thus the eastern Arab world) in 1982. The PLO’s upper echelons became “bourgeois, ideologically dependent on the US.” With the disastrous 1993 Oslo agreements the PLO transformed into “the only liberation movement that I know of in the 20th century that before independence, before the end of colonial occupation, turned itself into a collaborator with the occupying force.”

Said demolishes Oslo’s substance — the PLO’s implicit abandonment of UN Resolution 194 (which declares the right of Palestinian refugees to repatriation and/or compensation) and thus its desertion of the majority of Palestinians, who live in exile, in return for the “limited self-rule of the residents of the West Bank and Gaza.” And he demolishes Oslo’s style, down to chairman Yasser Arafat’s infuriating “thank yous” on the White House lawn — “the ‘nigger mentality,’ the white man’s nigger, that we are finally arrived and they’ve patted us on the head and we’ve been accepted and can sit on their nice chairs and talk to them.”

In a 1993 interview Said calls for a democratic reestablishment of the PLO as a unifying body. “We want,” he said, “a Palestinian census in every country where a Palestinian resides in order for there to be assemblies of Palestinians. Our problem is dispersion and representation.” Seventeen years later, though the crisis is even more urgent, this call has not been heeded.

Said himself was criticized by some for his “bourgeois humanistic approach.” Said had worked since the ’70s for a two-state solution and therefore recognition of Israel, and resisted a blanket boycott of Israelis, meeting frequently with peace activists. He understood the struggle as one between two peoples, two voices, two stories. Another thinker may have slid from here into an amoral, ahistorical liberalism in which both sides possessed equal claims and Palestine became “contested” rather than colonized territory. But Said didn’t follow this trajectory — he was too concerned with history and principle. What infuriated him most about Oslo was the erasure of Palestinian memory that it represented, the silencing yet again of the Palestinian narrative.

Certainly there were contradictions in Said’s positions. He understood the connection between the Palestinian cause and the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, a movement which resisted the notion of bantustan “homelands” for blacks as much as it resisted white supremacism, yet he still supported an unjust ethnic partition of Palestine. To his credit, he was always honest enough to recognize these contradictions. He was keenly aware, for instance, of the tensions between his backing for a mini-state and his abhorrence of narrow nationalism. He emphasized “the plural, the multicommunal aspect of Palestine … the intersection of many communities and cultures.”

By the end of his life, Said resolved many of the tensions by advocating a single, binational state. The shift is not visible in these interviews, but the elements underpinning it are. Said tells Barsamian that he first joined the PLO on the understanding that “we were not interested in another separatist nationalism … we were talking about an alternative in which the discriminations made on the basis of race and religion and national origin would be transcended by something that we called liberation … That, it seems to me, is the essence of resistance. It’s not stubbornly putting your foot in the door, but opening a window.”

It is disappointing that Haymarket Books didn’t provide better copy editing of The Pen and the Sword. To pick only the worst examples, “Arafat” becomes “Ararat” (a mountain in Turkey), “pied noir” becomes “pied notre,” and “hijra,” the Arabic word for migration, becomes “hyra.” But the editing is my only quibble. In these valuable interviews we observe a great mind working through knotty problems with humility and discipline. We are reminded too of Said’s lessons for the pro-justice movement in the West. While Arafat set great store on buying jewels for Hillary Clinton, Said recommended addressing Palestine’s story to “the media, the universities, the churches, the minorities, the ethnic groups, the associations, the labor movement.” The fact that this work has now begun is the greatest tribute to Edward Said and will perhaps be his greatest legacy.

The Brooklyn-based performance poet Suheir Hammad put it to me very well in Palestine. “We’ve lost Said and Darwish,” she said, “our towering figures, but thanks to them we now have tens of public intellectuals, writers, musicians, filmmakers at work. It’s a gain, not a loss.”

Robin Yassin-Kassab has been a journalist in Pakistan and an English teacher around the Arab world. His first novel, The Road from Damascus, is published by Hamish Hamilton and Penguin. He blogs on politics, culture, religion and books at qunfuz.com.

Related Links