The Electronic Intifada 19 February 2010

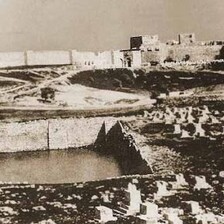

The grave of Ahmad Agha Duzdar al-Asali, the mayor of Jerusalem in the 19th Century, in the Mamilla cemetery. (Wikipedia)

Members of prominent Palestinian families from Jerusalem came out last week in protest against plans by the Simon Wiesenthal Center to build a Museum of Tolerance on top of part of the ancient Mamilla Cemetery where their ancestors are buried.

The initiative includes filing a petition in Geneva to various United Nations human rights bodies and to UNESCO, the Paris-based UN agency responsible for protecting the world’s cultural heritage. The petition was also addressed to the Swiss Government, which is the repository for the Geneva Conventions.

One family member behind the initiative said it is not just symbolic, but instead a full-blown campaign. He expects this issue to be included in a resolution being drafted for a March session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva.

In the East Jerusalem press conference at which this initiative was announced last week, petitioner Asem Khalidi noted that a number of men from Salah al-Din’s army, who liberated Jerusalem from the Crusaders, were buried in the Mamilla Cemetery.

Much of the momentum behind the initiative comes from Palestinians who grew up and who still live in the Diaspora, many of them in the United States. Press conferences were held in Jerusalem, Geneva and Los Angeles, home of the Simon Wiesenthal Center (and the first Museum of Tolerance, built in 1993), which says it is moving forward with its plans despite passionate legal and moral opposition.

Mamilla Cemetery

The corner of the Mamilla Cemetery slated for construction was paved over in the 1960s, and used as a car park. When excavations began on the site in 2005, human remains were found, and the chief archeologist stated that he believed there were many thousands of graves in many levels in that section of the cemetery.

The cemetery is situated in West Jerusalem, which fell under Israeli control during the fighting that surrounded the proclamation of the self-declared Jewish state in mid-May 1948. There have been no new burials since that time. From the May 1948 war, until the June 1967 war when Israeli forces captured East Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank, the cemetery was inaccessible to many if not most of the Palestinian families concerned, who were living under Jordanian administration.

The Simon Wiesenthal Center claims that it has spent a lot of money on reburying — in “a nearby Muslim cemetery” — the remains it has excavated there. However, a press release announcing the initiative of the Palestinian families said that “It was an active burial ground until 1948, when the new State of Israel seized the western part of Jerusalem and the cemetery fell under Israeli control … The construction project has resulted in the disinterment and disposal of hundreds of graves and human remains, the whereabouts of which are currently unknown.”

The Los Angeles-based center broke ground for the Jerusalem branch of the Museum of Tolerance in a corner of the Mamilla Cemetery in May 2004. California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger delivered the keynote address.

Families denied justice

There are 60 individual Palestinian petitioners from some 15 Jerusalem families including Adnan Husseini, the Palestinian Authority’s appointed Governor of Jerusalem; AbdulQader Husseini, the son of the late Faisal Husseini, who was the Palestine Liberation Organization representative in Jerusalem; and Sari Nusseibeh, head of Al-Quds University in Abu Dis.

Rashid Khalidi, Professor of History at Columbia University in New York, who is also a petitioner, has been closely involved in organizing this effort. In an interview with Democracy Now! he explained that the petitioners are asking that the Mamilla Cemetery be treated as a heritage site. “This is a cemetery where people have been buried since the 12th century … The fact that it is still being desecrated, not just by this Museum, but by vandalism of the remaining tombs, is a scandal”. He said the families were also asking for “reinterment of the excavated remains under religious supervision”, with information provided to the families about exactly where “within the cemetery.”

Palestinian and Israeli co-petitioners include the organizations Al-Haq, Addameer, Al Mezan Center for Human Rights, the Arab Association for Human Rights, Badil and the Zochrot Association.

Because it is in West Jerusalem, Palestinians have been hesitant to take any high-profile action asserting either physical or moral claims.

Until now, much of the opposition to the building plan has come from Israeli and Jewish rights activists who have argued, in part, that the construction on this site offended their Jewish beliefs and values. They have worked through the Israeli court system, and through appeals directed mainly to Israeli and international Jewish public opinion.

Gershon Baskin, co-director and founder of the Israeli Palestinian Center for Research and Information (IPCRI), told this reporter that the first he heard of the Museum of Tolerance project was in newspaper reports of the ground-breaking ceremony. “We came in only after the whole thing was licensed and all the legal proceedings were finished — and this is one argument that the court used against our petitions.”

The Israeli high court has recently dismissed another challenge and ruled that the Museum of Tolerance construction project is legal, and can proceed. Baskin believes that the legal avenues in Israel are now basically now closed.

Meanwhile, a private Palestinian offer to donate an alternative location for the Museum of Tolerance hasn’t been taken up by the Wiesenthal center.

At a public discussion sponsored by IPCRI in East Jerusalem in March 2009, attended by lawyers representing the Wiesenthal Center and the Museum of Tolerance project in West Jerusalem, Dr. Mohammad Dajani of Al-Quds University in Abu Dis offered to donate alternative land for construction of the museum in Anata near the concrete wall that Israel is currently building around the Jerusalem area. The offer was for 12 dunams (one dunam is approximately 1,000 square meters). At that alternative site, Dr. Dajani said to the public meeting, both Israelis and Palestinians could visit the future Museum of Tolerance — which many Palestinians would not be able to do if it were built in the heart of West Jerusalem, as is currently planned.

The lawyers for the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the Museum of Tolerance merely smiled, without replying.

About six months ago, Dr. Dajani said, he was surprised by an Israeli military decision to confiscate, “for security reasons,” about half of the parcel of land he had offered for the museum project. Just this past week, he said, he received a new notification that the military intends to take the remaining six or so dunams as well. He said he is challenging the order.

Marian Houk is a journalist currently working in Jerusalem with experience at the United Nations and in the region. Her blog is www.un-truth.com.