Tulkarem refugee camp 29 December 2009

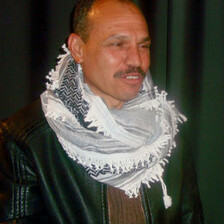

Sema Onbus in her home in the Tulkarem refugee camp. (Jody McIntyre)

The following is former Palestinian political prisoner Sema Onbus’s story as told to The Electronic Intifada contributor Jody McIntyre:

My name is Sema Onbus. I am 37 years old, from Tulkarem refugee camp.

My story starts when my brother was killed, on 6 September 2001, when an Apache [attack helicopter] dropped a bomb on him and his friends. It was the same day that my sister was due to get married, and he was on his way from Ramallah to visit the wedding when he was murdered. After my brother’s death, my husband decided to join the resistance, and started working with the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades. He had soon joined Israel’s wanted list.

On 28 October 2002, the Israeli army invaded the camp and started shooting at random, spraying bullets through the streets at anyone who happened to be in sight. My 15-year-old cousin was killed … they shot him six times. My husband was shot three times, twice in his stomach and once in his leg, but he survived.

On 28 March 2003, the army invaded the camp again. My husband was fighting back, and they killed him. His body was left lying on the street, riddled with bullets.

Forty days later, the army came to invade our home. They smashed through the windows and started destroying everything in the house, ordering the whole family out onto the street. They arrested my brother Abdullah, telling my father that they just wanted to talk with him for an hour. He was later taken to a military court, and sentenced to 13 years in prison.

Two months later, they came back to invade our house again. This time it was 2am, and again they ordered the whole family out onto the streets, including all the kids. It was extremely cold outside and pouring with rain … I pleaded with them to at least let the children sleep, but they didn’t care.

The military commander went over to my father and told him that they wanted his son Mohammed, again saying that they just wanted to speak to him for an hour. “Like the hour for Abdullah?” my father replied, “You said you wanted to speak to Abdullah for an hour, and now we don’t know where he is!” They told my father that Abdullah is a terrorist, and to go back into the house. They put a bag over Mohammed’s head, tied his hands and threw him into the back of one of the jeeps.

We thought they were finished, and were preparing to go back inside when the commander stopped my father. “We’re not finished,” he told him, “we want your daughter Sema.”

“Is it not enough that you have arrested two of my sons, and killed another?” my father asked. “Why do you want Sema?” The soldiers tied my hands behind my back, and I was taken into another jeep.

At the time I had four children — my youngest son was still breast-feeding, and my three daughters were aged two, four and five. “Now my daughter is in jail,” my father said to the soldiers, “what can I do with her children? You have killed their father, and now arrested their mother and destroyed the house they live in … who is left to look after them?”

I was taken to a military base called Qudomeem, and Mohammed was taken somewhere else … I don’t know where. They left me locked in a room for hours, until 11am, when some female and male officers came in and started beating me together. Afterwards, a commander came in and retied my hands, and I was taken to Jalemah prison, near Haifa.

I was placed in solitary confinement — a room measuring one meter by one meter, with black walls and no light, under the ground. I was to stay in that room for the next two months. The soldiers had a special system which they could use to change the conditions in the room, so in the middle of the winter they would pump in cold air to make it even more unbearable. I was so cold that my hands were swollen and I couldn’t feel my legs … it felt like I was sleeping in a freezer.

When they interrogated me, they told me that if I didn’t speak they would arrest my father and make my children homeless. Sometimes they brought in my brother and beat him in front of me, or beat me in front of him. They tried many things to make me speak, but it didn’t work. After 60 days of living like this, I was moved to a women’s prison called Timon. After six days I was taken to trial at a military court, and sentenced to two and a half years.

I saw a lot of suffering in Timon. The soldiers treated the women very badly; they would beat us, spray us with gas, and throw cold water at us. Our families weren’t allowed to visit, the prison was crawling with insects and mosquitoes, and solitary confinement was regularly used as a punishment. The food was terrible … one day it was beans, the next day macaroni, today beans, and tomorrow macaroni. If you were sick there was no properly trained doctor to help you, and the only thing you would be given was an Acamol [pain killer] and a cup of water, no matter what the problem. Almost all of the women in the jail were ill — because the prison was underground it was very damp, and this caused many health problems; some girls had their hair falling out, some had very bad teeth, and some had stomach problems. The cells had no windows, and this is where we spent all our time; we slept in the cells, ate in the cells, sat in the cells, and there was hole in the floor where we had to go to the toilet in the same room … because of this there were many diseases.

It is everyone’s dream in prison to be free, and when I heard it was time for me to be released I was so happy. When I got home, I was so excited to see my children and my brothers and sisters, but when I went to hug my son, who was now three and a half years old, he didn’t want to hug me. When I left my home he was still breast-feeding, but now I was a stranger to him. I kissed him instead, but he was too scared to sleep in the same house as me that night, so he went to stay with some relatives instead. He loved them because they had looked after him while I was in prison, so they had become like his family. After two and a half years away it was difficult for me to know how to look after my children, because it was like they had forgotten me, and of course, even more difficult for them.

It’s not easy to bring up four children without a father. I am responsible for them and everything they need — to put their food on the table, a roof over their heads, to find a school for them to go to. I have to be a mother and father to them at the same time … you really can’t imagine what this life is like.

The kids ask me about their father all the time. I tell them that he is a martyr and has gone to heaven. They ask me how they can go to visit. Once, my daughter told me to get a ladder, take a knife and climb up and cut open the sky so I could bring their father back. Another time, my son said to go to the place under the ground where my father is buried and break it open with a hammer so you can bring him back. My eldest daughter once told me to speak to God on Jawwal [the Palestinian mobile phone company] and tell him to let us see our father. All the time they ask me why they killed their father and not somebody else. They have so many questions … sometimes I don’t have an answer.

One day, my son asked me for a shekel. I said, “OK, here is a shekel,” but he said “I don’t want a shekel from you, I want one from my father.”

I live today, but I am afraid of tomorrow … afraid that one day I will not be able to provide my children with what they need.

I wish we had peace here, so I could know that my family is safe. Unfortunately, the Israelis do not want peace.

We can speak every day and every night about how we are suffering, but it seems that there is no one listening.

Jody McIntyre is a journalist from the United Kingdom, currently living in the occupied West Bank village of Bilin. Jody has cerebral palsy, and travels in a wheelchair. He writes a blog for Ctrl.Alt.Shift, entitled “Life on Wheels,” which can be found at www.ctrlaltshift.co.uk. He can be reached at jody.mcintyre AT gmail DOT com.