The Electronic Intifada 4 September 2009

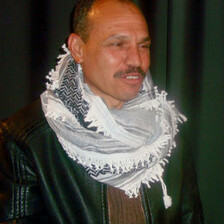

Haitham a- Katib at home with his son Mohammed. (Hamde Abu Rahme)

Haitham al-Katib is a journalist living in the occupied West Bank village of Bilin. During the last few months, village residents have been the victims of constant night invasions by the Israeli military. The goal of these raids is to crush the village’s campaign of nonviolent resistance to the confiscation of their land. Al-Katib films the night raids, as well as the weekly nonviolent demonstrations against the wall, and has become a well-known figure for his brave attempts to document the struggle. The Electronic Intifada contributor Jody McIntyre, currently based in Bilin, interviewed him about his work.

Jody McIntyre: What’s your daily routine at the moment?

Haitham al-Katib Because of the raids, I don’t sleep at night. Instead, I walk around the village with friends as well as international volunteers, to watch for soldiers. They come with dogs and masked faces, and break into the houses without knocking on doors, usually between 2 to 4am, so now our children are terrified that it will be their house next. When I was 15 years old I was put in jail myself, so I know how it feels. I was only a kid, and I was really afraid, so now I feel like I have a responsibility to try and stop it from happening to our next generation.

On Fridays, I film the nonviolent demonstrations at the wall. The occupation forces have stolen over half of our land to build settlements and the wall, so we go to protest against this. This year, at one such demonstration, they killed a close friend of mine, Bassem Abu Rahme. He had his arms in the air and was telling them not to shoot because they had injured an Israeli girl, and they murdered him right there. I used to be a photographer, but after that incident I realized how important video is to show the truth; the Israeli army later claimed that Bassem was hurling rocks at them when he was shot. I was photographing Bassem at the time and I thought he was just injured, but when I realized something wasn’t right, I dropped my camera from the shock.

JM: How do the night raids affect your family life?

HK: I’ve lost my regular job as an electrician since the night raids began, so now my family and I are in a very difficult situation financially. Not just my family, but everyone in the village sleeps in normal clothes now, fearing they could be the next person to be dragged from their bed with automatic weapons pointed at their face. I can’t sleep in my house at night, because I know there could be another invasion, and I want my children to sleep instead.

My youngest son, Karme, is two years old; he was diagnosed with leukemia at just eight months. I used to take him to the hospital in Jerusalem every day, but recently I’ve been finding it increasingly difficult to obtain the permit I need from the Israeli authorities, so my wife goes instead. The [Palestinian Authority] was paying for Karme’s healthcare, but its support is unreliable - earlier this year it suddenly stopped paying for a month, and I had to find 20,000 NIS [New Israeli Shekels, about $5,255] for the medical costs. There is no way my family can afford these hospital fees.

JM: Why do you film the night raids?

HK: Because I feel a [sense of] duty to show the world the reality of what is happening in Bilin. Also, I think if my camera wasn’t there the Israeli soldiers would be even more brutal, and would stay in the village for longer during the raids. We also go out with the intention of stopping the violent arrests of our children, although that has proven impossible.

JM: Have you ever been hurt while filming?

HK: Yes, many times! During a recent night raid, I saw the soldiers looking to grab me, so I started running and gashed my leg on a piece of metal that was sticking out from underneath a car. The soldiers just left me when they saw I was lying on the ground.

In fact, they often attack me during the raids and try to break my camera. In the most recent raid they succeeded — one of the soldiers saw me filming and grabbed the screen of the camera, yanking it twice to completely destroy it.

I’ve also been injured many times during the weekly nonviolent demonstrations at the wall. On one occasion, I was photographing and a soldier told me if I didn’t stop he would shoot me in the head. I didn’t believe him, so I stepped to the side and continued to take photos, and he shot me with a rubber-coated metal bullet right between my eyes, which broke my skull. While I was lying in intensive care, the one question on my mind was, “Why?” I didn’t do anything wrong, I was just taking photos, but perhaps the soldiers didn’t want the world to see the truth of their actions, while they preach about Israeli “democracy” in the mainstream media.

But it’s not only me; hundreds of people, including many journalists, have been injured during our nonviolent demonstrations.

JM: What are your plans for the future?

HK: My dream is to teach lots of people in the village how to film, so that when the mothers have their children snatched from them they can show the whole world.

Next week, I am going to Switzerland with Shai Pollak, an Israeli activist and filmmaker, and close friend of mine, to show Bil’in, Habibi [a film Shai made about our village’s campaign of nonviolent resistance] at the Biennale libre de l’image en movement film festival in Geneva. I hope we can use the film to show the world that the wall is not for security, as Israel claims, but solely for stealing our land and building illegal settlements.

JM: Do you see an end to the occupation?

HK: I think our struggle for freedom may continue for a long time, but I truly believe we will get there one day. If Palestine follows the model of Bilin, we will be free.

Jody McIntyre is a journalist from the United Kingdom, currently living in the occupied West Bank village of Bilin. Jody has cerebral palsy, and travels in a wheelchair. He writes a blog for Ctrl.Alt.Shift, entitled “Life on Wheels,” which can be found at www.ctrlaltshift.co.uk. He can be reached at jody.mcintyre AT gmail DOT com.