The Electronic Intifada 19 July 2009

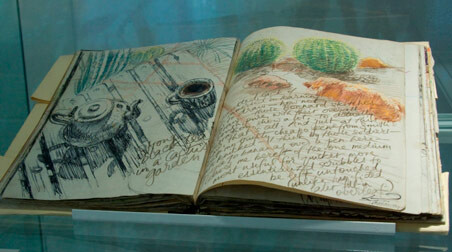

One of Ali Jabri’s sketchbooks on display in Amman.

Ali Jabri locked his paintings in a trunk. It had been more than 20 years since the artist had opened it, but after he was murdered in his Amman, Jordan apartment in December 2002 his friends decided it was time to tell Jabri’s tale. Six years in the making, Fadi Ghandour, a philanthropist and friend of Jabri’s, set up a foundation to document and preserve the late artist’s work. In a home Jabri had wished to one day own, the Ali Jabri Human Heritage Foundation was launched in Amman.

On a Wednesday evening a somber crowd gathered for the first of Jabri’s exhibitions since his death, titled Journey Back, a collection of his sketches, collages and paintings from the time he spent in Cairo, a place he passionately loved.

“It’s not about art, it’s about commentary … we are bringing [Jabri] back to life for everybody to see. Jabri did not like to be in the public eye, but now he is in the public eye because he needs to be known. He’s a national treasure and a national treasure needs to be protected, it needs to be available to everybody,” Ghandour, chairperson of the Jabri Foundation, said.

Born in Jerusalem in 1943 to a prominent Aleppo family, Jabri spent his formative years at Victoria College in Cairo (where Edward Said had also been a pupil). It wasn’t until he left for California in the 1960s, his friends say, that he truly embraced his artistic personality. Despite his studies in architecture at Stanford University, Jabri opted for a bohemian life: beaches, drugs and frequent romantic encounters. He then moved to the UK and studied English literature at Bristol University, eventually moving back to the Middle East: first to Egypt, where he lived for one year, then, finally, settling in Amman. “[Egypt] is the period of time when he first considered himself as a professional artist. It was his journey back to the East, so it was fitting that we opened the exhibit with that journey,” Hanya Salah, director of the Jabri Foundation, said.

One of Jabri’s paintings on display in the exhibit.

A lot of attention in Jabri’s work was inspired by Cairo’s atavistic prevalence. He painted mosques and Islamic settings, but the skyline of the minaret was never more than the background of his piece. His focus was more on the people of Egypt, whom he greatly adulated. In one of his sketches, a homeless man is sprawled on the floor, asleep near the entrance of a mosque. In another of his works — a multi-layered mixed medium sketch — the artist superimposes his self-portrait, blending his face into the architectural design of a mosque. He was also fascinated, it seems, with his grandfather (with whom he initially lived in Cairo). Displayed again and again on a wall were profiles in pastel, ink and charcoal of the blue-eyed man who in every photo wears an astrakhan hat with a suit and tie. Jabri poked fun at his jiddo, writing in his journal: “… and poor grandpa round One Hundred Years of Age, the old Lampedusa Aristocrat himself, in eight layers of pre-war English tailoring …” Jabri was known by his peers to be sarcastic. “Jabri’s journals are full of parody and tirades against the colonial and homegrown rulers for whom the ‘little people’ didn’t really matter,” Salah said.

Wherever he went in Egypt, Jabri carried a journal with him. He took notes as he journeyed across both the city and countryside, whether he was sitting on the beach or drinking his coffee — Jabri replicated all that caught his eye. At the exhibition was a room dedicated exclusively to his sketchbooks where the artist’s Cairo journals are archived into stacks three-feet-high, most of which are mixed media, juxtaposing narratives and images together. The theme is “Youth, Eros, Time, Art, Life.” One sketch is of a naked woman from the chest up: her head tilted up, a cigarette in her lips, eyes closed in an orgiastic state. Written across the painting is the word asrar (secrets) in an elegant Arabic script.

The artist had a particular obsession in drawing what he called “city kitsch,” essentially sketching all that he could of Cairo’s harsh streets, or as Jabri summarized in one of his journals: “… the dichotomy persists between ancient beauty and modern Warholian junk,” referring to the iconic American pop artist Andy Warhol.

It wasn’t until his relocation from Cairo to Amman that Jabri incorporated political and social commentaries into his art. Using different newspapers and magazines of the Arab world during the 1980s, he created a satirical 12-piece collage, from “The Prayer Call” — a disjointed piece with lascivious photos of two men — to the “Director of Antiquities,” where a clipping of a suit-clad Westerner is pasted over ancient Egypt. The collage ends with what Jabri considered to be an allegory to the “modern Arab world”: magazine clippings of a marching militia, a cadaver and wine — all images layered into a piece titled “And now.”

While it’s still unclear who killed Ali Jabri, officials in Jordan say it was his Egyptian lover, a man Jabri’s friends never met and who “mysteriously disappeared.”

All images by JO Magazine.

Sousan Hammad is a journalist based in the West Bank city of Ramallah. She can be reached at sousan D O T hammad A T gmail D O T com.

Related Links