Electronic Lebanon 9 June 2009

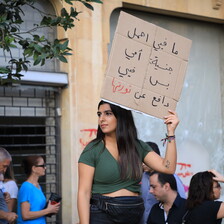

Lina Abou-Habib at her CRTD-A’s offices in Beirut. (Matthew Cassel/IPS)

Campaigners have succeeded in securing that right in countries such as Egypt, which amended the law in 2004 to allow women to pass citizenship to their children, and in Algeria, which granted women full citizenship rights in 2005. In Lebanon the struggle continues.

“Lebanon is the worst,” says Lina Abou-Habib, director of Collective for Research and Training on Development-Action (CRTD-A), a group leading the campaign for women’s right to citizenship. Abou-Habib argues that the position in Lebanon is at variance with the popular belief that women in Lebanon have more rights than in other Arab countries.

“Images of Botox women driving big yellow 4X4s does not mean that these women are enjoying their rights,” Abou-Habib told IPS. People outside Lebanon look at only a “small island of prosperity.”

CRTD-A began its citizenship campaign in 2002 as part of a larger effort to support women who face inequality in the male-dominated Lebanese society. In the last parliamentary election in 2005, only three women were among the 128 members elected. The campaigners are hoping for more after the next election Jun. 7.

“It’s crucial before the parliamentary elections because the only person in the government who finally got to understand the campaign is [Lebanese minister for the interior] Ziad Baroud,” says Abou-Habib. Campaigners fear that Baroud, a lawyer who was a part of the campaign before taking office, and has supported it since, could lose his position in a new government.

They now want to make sure that the issue of citizenship rights for women remains on the table, and can be picked up by the incoming government.

Under the current law, written in 1925 and modified slightly in 1994, Lebanese women cannot pass their citizenship to their spouse or children. In a country of only about four million, but with as many as 400,000 Palestinian refugees and tens of thousands of Syrians and other nationalities, this lack of rights for women is affecting many families.

Non-Lebanese citizens face difficulties receiving equal social services such as healthcare, education and welfare, and in many cases are prevented from working.

For Palestinians, the issue goes back 60 years when most came to Lebanon after being forced from their homes in 1948 when the state of Israel was created. They have never been given Lebanese citizenship or equal rights.

Special laws bar Palestinians from working in more than 70 professions in Lebanon. And without nationality, the children are affected as well.

Sharif Bibi, a 30-year-old graphic designer from Beirut, spoke to IPS about issues he faces as the son of a Palestinian father and Lebanese mother. “I had to quit my job last month because of the discrimination that I faced. I was underpaid, and social security tax was deducted from my pay check even though I don’t benefit from it.

“I was born in Lebanon, my grandfather is Lebanese, my uncles, cousins are all Lebanese, and I know Lebanon better than some of my Lebanese friends. I don’t understand why I’m not eligible to be treated like any other Lebanese person.”

Some lawmakers say these restrictions protect Palestinians’ right to return to Palestine guaranteed to them by UN General Assembly resolution 194 that was passed months after their exile in 1948.

Abou-Habib dismisses this argument. “If they’re so worried about the right of return, why don’t they say anything in situations where Palestinian women are married to Lebanese men?” Abou-Habib says this is an issue about women’s rights, and “not one that should be tied to the Palestinian question.”

The citizenship law means that many feel discriminated against in their own community. Abir, a saleswoman at an upscale clothing store in Beirut who chose not to give her last name, became visibly uncomfortable when asked about her nationality.

“The discrimination I’ve experienced for being who I am has made me depressed over the years when I was growing up,” she told IPS. “I sent many job applications, and it’s either I don’t get any call from the job; or, I have seen the employer throw my job application in the trash bin after finding out what I am.

“The truth is that my mother is from south Lebanon and my father is Syrian, and we live in Beirut,” she says. “It is really difficult sometimes when I meet people and they ask me where I’m from. Now I say I’m from Beirut, to avoid discrimination.”

Many lawmakers say that modifying citizenship laws would greatly alter the fragile demographics of the country. Abou-Habib says the sectarian make-up of Lebanon is one of the leading reasons behind the “racist and discriminatory policies…lawmakers do not understand their job. They don’t know that their job is to secure people’s rights.”

Bibi and his family live without those rights every day. “It’s sad because my mother always feels it’s her fault. She feels that after she married a Palestinian man they stopped treating her like a Lebanese citizen, and it made her feel like a second class citizen, or not even a citizen at all.”

All rights reserved, IPS — Inter Press Service (2009). Total or partial publication, retransmission or sale forbidden.