Gaza City, Gaza Strip 19 May 2009

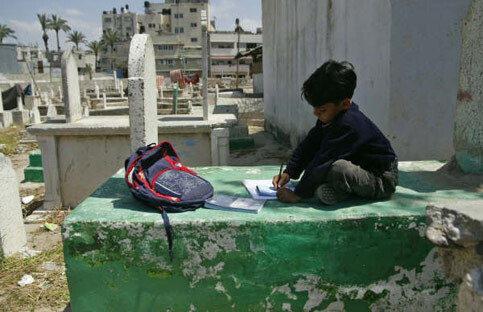

Four-year-old Mahmoud does his homework atop a grave in the al-Sheikh Shaban cemetery. (Eman Mohammed)

The scene of Mahmoud Jilu, four years old, rolling his ball with friends doesn’t seem weird at all until you see where he is playing. Mahmoud runs after the ball into a backyard full of graves forming the cemetery where his family has lived since they can remember.

The six-member Jilu family are all jammed together in a tiny house with one bedroom and a small space for the kitchen with a tomb next to it. For Afaf Jilu, 30 years old, the mother of three boys and one girl, it’s not the surrounding view of graves that upsets her the most but the cramped environment that forces her to live in one room with her husband and four kids.

“Not having privacy is what makes this life unbearable,” Afaf said. “When I try to sleep, my children want to watch TV and they are only kids. I can’t make it worse for them by denying them what they want to.”

Afaf added, “I keep reminding myself that we’ll get our own house once the economic situation in the country is better and then I can plant lots of trees around the house instead of having a cemetery strangle us from all around. We all hang on our small dreams that we have in mind to achieve. That’s the best thing we learned from living here; the more we see people dying, leaving their dreams behind, the more we hold on to ours. It’s the only way to break through!”

For 13-year-old Muhammad, the equation is different since he never brings any of his friends over to play or study, because of his feeling of being the “odd one out” since he lives in a cemetery. “My friends aren’t familiar with the idea of living between dead people. It can be used to make a silly joke and not just a reality of life. Sometimes I feel ashamed of this place,” he said.

Afaf Jilu in her family’s kitchen. (Eman Mohammed)

Sixteen-year-old Nour disagrees with her brother since she feels free to invite her friends from school to her “one-of-a-kind” house. “I don’t get a hard time from girls at school because of where I live. It’s such a superficial thing to do — only kids think that way. They respect me for who I am and not because of where I live. Plus, many families lost their houses recently after they were destroyed in the war and they aren’t ashamed, so why should I be?” Nour said she dreams someday to go college and become a nurse. She said she wants to work with patients in hospitals and to be called an “angel of mercy.”

Suhail Jilu, 43, works as a taxi driver and is the breadwinner for the family. His family has been living in al-Sheikh Shaban cemetery in the middle of Gaza City since 1948, when they were expelled from their lands in Jaffa by Zionist forces. He works two jobs, and also helps with the funerals occasionally held near his home in order to save enough money for a new house. Suhail recently received an official warning from the authorities to evacuate his home because it is located on government lands.

He explained in a desperate tone, “Who would want such a life for himself and his kids? Both the situation and the government are down our throats! As if we have any other options!”

Suhail added, “We have dreams to look forward to and a different kind of life away from death and misery. Our situation wasn’t any better than others during the last war; in fact it was worse, dealing with death with the funerals all day every day. Nothing could be more harmful to my children’s mental health than this.”

Like others in Gaza, the Jilu family has been struggling with the dire economic situation due to the Israeli siege. In spite of their desperate attempts to leave the cemetery, they haven’t been able to move out of their house. The Jilus are still caught in the middle between being evicted and having no alternative home, and the suffocating, increasing number of graves all around them. Living amongst the dead is a bitter reality for souls dreaming of a better life.

Eman Mohammed is a Jordanian-Palestinian freelance photojournalist and reporter based in the Gaza Strip since 2005.