Gaza Strip 29 January 2009

One family’s story

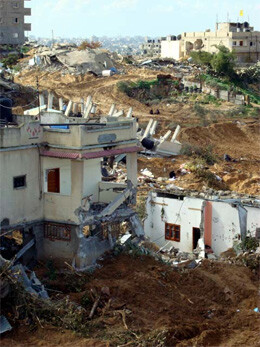

Destruction in Izbet Abed Rabu.

I start to tell the stories of Ezbet Abbed Rabu, eastern Jabaliya, where homes off the main north south road, Salah al-Din, were penetrated by bullets, bombs and/or soldiers. If they weren’t destroyed, they were occupied or shot up. Or occupied and then destroyed. The army was creative in their destruction, in their defacing of property, in their insults. Creative in the ways they could shit in rooms and save their shit for cupboards and unexpected places. Actually, their creativity wasn’t so broad. The rest was routine: ransack the house from top to bottom. Turn over or break every clothing cupboard, kitchen shelf, television, computer, window pane and water tank.

The first house I visited was that of my dear friends, who we’d stayed with in the evenings before the land invasion began, with whom we had huddled in their basement as the random crashes of missiles pulverized around the neighborhood. I worried non-stop about the father. After seeing he was still alive, I’d done the tour, from the bottom up. The safe-haven ground floor room was the least affected: disheveled, piles of earth at bases of windows where it had rushed in with a later bombing which caved the hillside behind, mattresses turned over and items strewn. This room was the cleanest, least damaged.

Upstairs to the first level apartment, complete disarray. Feces on the floor. Broken everything. Opened cans of Israeli army provisions. Bullet holes in walls. Stench.

To the second floor, next two apartments, all of the extended sons and wives and children’s rooms. More disarray, greater stench. This was the soldiers’ main base, as can be ascertained, from the boxes of food — prepackaged meals, noodles, tins of chocolate and plastic-wrapped sandwiches — and the clothing left behind by the occupiers. A pair of soldier’s trousers in the bathtub, soiled with shit.

F. tells me: “The smell was terrible. The food was everywhere. Very disgusting smell. They put shit in the sinks, shit everywhere. Our clothes were everywhere. The last time they invaded [March 2008], it was easy. They broke everything and we fixed it. But this time, they put shit everywhere: in cupboards, on beds — my bed is full of shit.”

She is strong and has handled the invasions before, but the desecration of her house has got her down.

“A minute ago, Sabreen opened her clothing cupboard: there was a bowl of shit in it! They used our clothes for the toilet. They broke the door of the bathroom and brought it into our room. I don’t know why.”

The door lies sideways on the floor of her bedroom, which itself looks like a tornado has taken apart. “They took out my lingerie and left it lying everywhere,” she goes on, listing the personal grievances which are more hurtful than the financial wreckage.

As F. continues to clear the soldiers’ mess, she talks about her family’s state of mind. “Abed [her young nephew] is very afraid, he wants to leave because of the zenana,” referring the drones which fly overhead despite the ostensible ceasefire unilaterally declared by Israel on 18 January and violated by Israel since then.

Where a mosque once stood.

Land torn up by tank treads.

“A professional army”

When I visited two days later, the house much tidier but still soured with the clinging stench of the soldiers’ presence. “We’ve cleaned as much as we can, but it’s so difficult. We still don’t have running water, we have to fill jugs from the town water supply.” From walking the sandy track, I know how hard it is even empty-handed on foot, let alone laden with heavy jugs or trying to navigate any sort of wagon to carry large amounts of water. The track had been more of a proper dirt road before it, and the land around, was torn up by Israeli tanks and bulldozers.

From the kitchen balcony I look out and see razed land below, bombed houses, the jumeiza tree beyond, burned but somehow still standing amidst the ruins. The cement water tank that had survived previous raids and that was there last month was finally gone, destroyed by aerial bombing.

From the living room window we look out on the hilltop area behind which F. had already explained had hosted invading Israeli troops in the past. This time tanks not only amassed but created a massive earthen arena in which Israeli soldiers brought detained Palestinians. One neighbor, F. tells me, was taken there. He, 59, and his son, 19, were led there at gunpoint and stripped to their underclothes. The occupying soldiers surrounded them in tanks, in a circle. “We hadn’t done anything wrong,” they told F. later. They were detained in Israel for three days in solitary confinement, blindfolded, handcuffed, intermittently interrogated, beaten and interrogated again, asked “Do you have tunnels at your home? Where are the fighters? Where are the rockets? Do you know anything about Hamas? We will destroy your house if you know anything.”

F.’s sister, A, describes their 17 days at the Foka school, after evacuating their al-Tatra home. The schools which were to be a safe-haven (but were in reality not, as seen with al-Fakhoura and the other UN schools that were bombed and hit with what is almost certainly white phosphorous) were no YMCA, not even with the most basic of amenities, certainly not warmth, hot drinks, restful nights.

“We couldn’t sleep at all at night, we were very frightened. There was no security. Where could we go? We had no where to go. We were 35 people in one small classroom. There weren’t any mattresses, no covers. It was cold, very cold, at night. No electricity. No water. The few bathrooms in the school had to serve hundreds of us; they were overcrowded, filthy. Our relatives were able to get us blankets after the first four days, then it was better. But we didn’t have enough to eat, only a little bread, not enough for a family, and canned meat.”

The usual perspective and gratitude for surviving overrides what is her right to be indignant, depressed, to cry and lament their suffering.

“Thank God we have a room in our house. Many people’s houses were completely destroyed,” she says of her own seriously-damaged house. The soldiers who ransacked, destroyed their clothes and shelled the home also stole a computer and 2,000 JD,” she tells me. Why would she lie? I know the family to be honest, not deceitful. They have no reason to fabricate the thievery. And theirs is not an isolated case.

Amnesty International sent a fact-finding team to Gaza following the Israeli attacks. Chris Cobb-Smith, also a military expert and an officer in the British army for almost 20 years, said “Gazans have had their houses looted, vandalized and desecrated. As well, the Israeli soldiers have left behind not only mounds of litter and excrement but ammunition and other military equipment. It’s not the behavior one would expect from a professional army.”

And that was just one family’s story.

A life interrupted.

Salvaging belongings.

Psychological terror

Two of her boys worked to pull pieces of clothing, books and anything reachable from under the toppled cupboard. Every item is sacred. The mother led me through her house, pointing out the many violations against their existence, every graffitied wall, each shattered window, glass and plate, slit flour bags — when the wheat is so precious — and the same revolting array of soldiers’ left-overs: spoiled packaged food, feces everywhere but the toilet, clothes used as toilet paper. The same stench.

“They broke everything, broke our lives. That was the boys room.” We continue through the wreckage. “Look, look here. See that?! Look at this!” This is to be the refrain as we step over destroyed belongings into destroyed rooms.

It isn’t only the destruction, defiling, vandalizing, waste. It’s also the interruption of life, a life already interrupted by the siege. She held out school books, torn, ruined, and asked how her children were supposed to study when they have no books, no power, had to flee their home, are living in constant fear of another bombardment of missiles (from the world’s fourth most powerful amilitary).

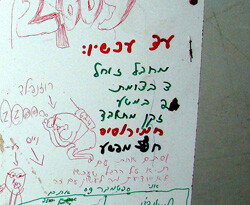

Graffiti left by Israeli soldiers reads: “Until now/ A crawling saboteur (terrorist)/ 3 in the junction/ 2 in the plantation/ A suicide-old man/ [illegible]/ An innocent.”

“We don’t hate Arabs, but will kill every Hamas,” and “IDF [Israeli army] was here! We know you are here. We won’t kill you, you will live in fear and run all your lives!”

For surviving members in families like hers, this psychological terror is real. For those who have been killed already, the “we won’t kill you,” is a lie. Ask the surviving fathers, mothers, siblings and children.

From the rooftop, we see neighboring houses inflicted with the wrath of the Israeli military machine. And great swathes of land that once held homes and trees, now naked, stubbled with pillar fragments at painful angles, rubble, stumps and tank tracks.

“Here, here, come look over here, over here.”

“That was all our land: clementines, lemons, olives …”

“That’s my brother’s house over there, its all broken …”

The drones were still overhead, the words too urgent, too many, too fast, too dizzying.

Down to ground zero and on to more newly wrecked houses and lives. Past a water pump which served at least 10 houses in the area, hit by missiles, ruined.

Passing more shells of houses, I meet Yasser Abu Ali, co-owner of a paint and tools supply shop bombed to the ground by two F-16 missiles. Seventeen people were immediately dependent on the revenue from the business, not accounting for indirect dependents (suppliers, buyers). As Abu Ali tells of his and his brothers’ $200,000 loss, it is revealed that he is a cousin of Dr. Izz al-Din Abu al-Eish, the doctor whose three daughters and niece were killed by Israeli shelling on his house in Jabaliya. Everyone has their own story, and stories overlap, tragedies overlap and compound.

Samir Abed Rabu’s damaged home.

The house is more holes than walls, from multiple tank shells to automatic gunfire shots from the tanks. Seeing so many intentionally and deviously-ruined houses dulls the concept of damage. But strangely some things stand out as odd or notable amidst the wholescale destruction. Entrails of ceilings and support beams hang in threads. A chair sits gutted.

And there are the sniper holes. I look out the hole facing Salah al-Din street, at the Dawwar Zimmo crossroads, and I realize that it was from one of these very holes that the emergency medical worker Hassan would have been shot, thankfully not killed (unlike the 13 other emergency medical workers). Thankfully we also weren’t shot dead. These sniper holes litter house walls in homes all over Jabaliya, al-Tatra, al-Zeitou — all over Gaza.

The baby’s bedroom was not spared from the attacks. A wall of cheerful cartoons and cute baby posters contrasts the ugliness of the gaping shelling wounds, a reminder that nothing is sacred to an army that will shoot children point-blank.

The rotting donkey out back explains the stink, a stench different than that of the army’s usual odor.

Leaving Samir Abed Rabu’s ruins, I see a newly homeless family making tea over a fire, behind the rubble of their former home.

Saed Azzat Abed Rabu stands under a missile hole in his bedroom ceiling, explaining that on the first day of the land invasion, he and family had been in the house when a missile struck it. They frantically evacuated to a school and only learned of their house’s post-occupation demise upon returning after the Israeli soldiers left.

It is like the others: ravaged, left with soldiers’ waste and wine bottles — Hebrew writing on the label (wine isn’t available here anyway, so there’s no question who drank the wine), rooftop water tank blown apart, and rooftop views affording more sights of neighborhood destruction and of the lemon trees that once stood near Saed Abed Rabu’s home.

I left Abed Rabu that day, weaving among taxis, motorbikes, trucks and carts packed with belongings, people who had no home to stay in, who’d only come to retrieve what they could from their former lives. I’d seen more than I felt I could internalize or reproduce for others, but knew I’d go back for more stories because I knew there are more. More than I can possibly hear or pass on.

A house violated

Yousef Sharater and children in front of their damaged home.

In the second story front room the original window is flanked by gaping holes ripped into the wall by the tank missiles that targeted his house. “They were over there,” Shrater says, pointing just hundreds of meters away at Jabal Kashef, the hilltop overlooking the northern area of Ezbet Abed Rabu.

In the adjacent room, Shrater points further east to where more tanks had come from and stationed. “My wife, children and I were in this room when they began shelling. We ran to the back room for safety, hoping it would be some protection.”

The back room is another haze of rubble and bits from explosions. The tanks had surrounded the entire Abed Rabu area and no sooner did the family take shelter in the back room when a new shell tore into the house, fired from tanks to the south of the house. “It hit only a meter away from the window,” he points out, and leaning out the window and looking up, the hole left from the tank shell is just one meter above. “If it had come into the room, we’d be dead.”

Shrater explains how the Israeli soldiers forcibly entered the house and ordered the family members out, separating men and women and locking them in a neighboring house with others from the area. His father and mother, living in a small shack nearby, were soon to join them. The soldiers then occupied the house for the duration of the land invasion, as Israeli soldiers did throughout the Abed Rabu area, as they did throughout all of Gaza. And as with other houses in occupied areas, residents who returned to houses still standing found a disaster of rubbish, vandalism, destruction, human waste and many stolen valuables, including mobile phones, gold jewelry, US dollars and Jordanian dinars (JD), and in some cases even furniture and televisions, used and discarded in the camps Israeli soldiers set up outside in occupied areas. Shrater says the soldiers stole about USD 1,000 and another 2,000 JD (approximately USD 828) in gold necklaces.

Yousef’s father who suffers from asthma.

The whole house has sniper positions. Sniper holes adorn each of the two west-facing rooms overlooking the Dawwar Zimmo crossroads, where bodies were later found shot dead and unreachable by family members or emergency medical teams (including the Red Crescent medics who were shot at, one hit in the thigh, when trying to reach a body on 7 January).

From the roof we see more clearly the surrounding area where tanks were positioned, the countless demolished and damaged houses and buildings, and bits of shrapnel from the tank missiles. Shrater’s father, 70, is on the roof, and begins to tell of his experience of being abducted from his house and locked up with his wife and others for four days. “They came to our house there,” pointing to the low-level home which housed him, his wife and their sheep and goats. “The Israeli soldiers came to our door, yelled at us to come out, and shot around our feet. My wife was terrified. They took all of our money, then handcuffed us. Before they blindfolded us, they let our goats and sheep out of their pens and shot them. They shot eight dead in front of us.”

The elderly Shrater, who suffers from asthma, and his wife Miriam were then blindfolded and taken to another house where for the next four days Israeli soldiers denied him his inhaler and his wife her diabetes medications. Food and water were out of the question, and Yousef Shrater’s father says their requests for such were met with soldiers’ retorts of “No, no food. Give me Hamas, I’ll give you food.”

Mariam Shrater, still terrified from her four-day ordeal.

The house between Yousef Shrater’s and his parents has also been damaged. The asbestos roofing lies in hefty chunks on the floors of the bedrooms and kitchen, save for where it hangs precariously in the underlying waterproofing plastic sheeting, along with the heavy concrete blocks used to weigh the tiles down. The kitchen is black with soot from what must have been another white phosphorous fire, and empty shells lie in the burnt wreckage of the fire. Two metal doors from the factory across the street from Shrater’s house, bombed by an F-16, are lying near the kitchen, having blasted clear across the street and over the roof of Shrater’s house.

Mahmoud Shrater, Yousef’s brother and also an inhabitant of the main house, is at the house, clearing some of the rubble, sifting. “We need tents to live here now,” he says, standing in the shell of what was their home.

All images by Eva Bartlett.

Eva Bartlett is a Canadian human rights advocate and freelancer who spent eight months in 2007 living in West Bank communities and four months in Cairo and at the Rafah crossing. She is currently based in the Gaza Strip after having arrived with the third Free Gaza Movement boat in November. She has been working with the International Solidarity Movement in Gaza, accompanying ambulances while witnessing and documenting the ongoing Israeli air strikes and ground invasion of the Gaza Strip.

Related Links