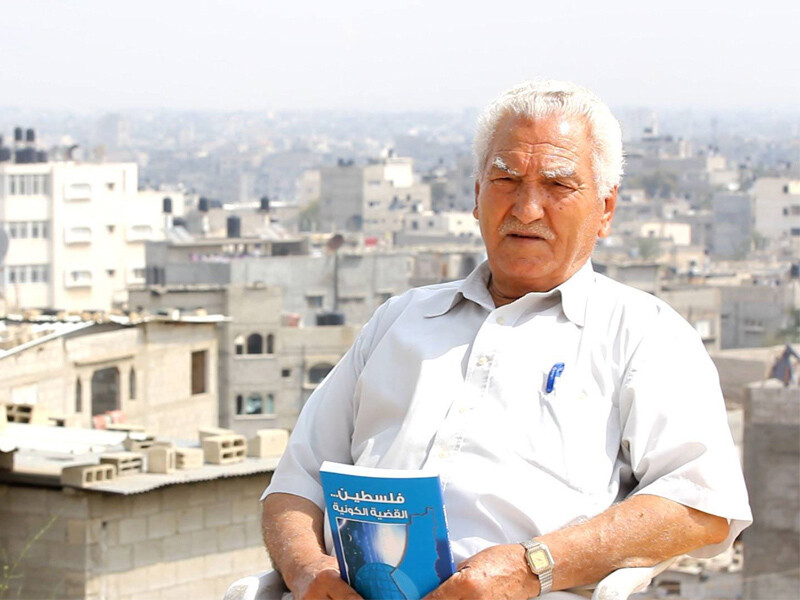

The Electronic Intifada Nuseirat refugee camp 29 May 2014

Ahmad al-Haj was 15 when he was expelled from his village in 1948.

Ain MediaEarlier this month The New York Times referred to the “destruction of Arab villages in battles that led to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.”

The testimony of Ahmad al-Haj, however, exposes that paper’s version of events as dishonest.

Rather than being the victim of “battles” — a term that implies fighting between two armies of similar strength — this octogenarian was forced from his home in a carefully planned campaign of ethnic cleansing by Zionist militias. The ethnic cleansing is known to Palestinians as the Nakba — Arabic for catastrophe.

Al-Haj was just 15 in 1948. Like many other young Palestinians, he was already working in agriculture.

One day in April that year, he was returning to his village, al-Swafer al-Sharqia, after going to an area market. To get home, he and his mule had to pass through nearby Julis, which, he was told by a passerby, had been taken over by Zionist forces.

“I thought nothing would incite those people to try to kill an unarmed, small boy passing peacefully on his way,” he told The Electronic Intifada.

He was mistaken. The only way he could survive was to throw himself off his mule and sprint.

“The mule ran faster than me,” he said. “The machine gunners stopped shooting when their bullets could no longer reach me.”

When he arrived back home, his parents were standing in the yard they used to thrash wheat. “My father and mother took me into their arms and kissed me and thanked God for my safety,” he said.

Attacked

The following month, Zionist forces attacked a village next to al-Swafer. His family had moved to that village to tend to their crops.

During the attack, al-Haj’s father went missing. At first, the family thought he had been killed. Four months later, they learned from the Red Cross that he was in prison.

Contrary to what The New York Times implied, Palestinians did not have the means to defend themselves against their Zionist assailants. “My father owned a gun, but he had only twenty bullets to fight with,” al-Haj said.

He added that whereas Zionist militias were well-armed, the British Mandate forces — then in charge of Palestine’s security — used to search Palestinian houses and farms, confiscating any weapons they found.

The disappearance meant that al-Haj assumed many of his father’s responsibilities. He told his sisters to stop crying as his father may have been captured, rather than killed. “Weeping and wailing will not bring him back,” he recalled commanding. “We have many things that we should do in the absence of our father. Let us have something to eat then get up to work.”

Thirty Palestinian villages in the Gaza district were forcibly evacuated between 15 May and 11 June 1948. They included al-Swafer.

Brutal

“My village was brutally attacked and burned down by the Zionist army and we were forced to flee the burning village to the adjacent village of Hatta,” al-Haj said.

His family then sought refuge in nearby Falluja, where the Egyptian army was based. Within a few days, they had to flee again.

“Zionist warplanes attacked the village. It was a Friday. We had lunch at the house of one of our relatives. A man pushed me out and took my position when the warplanes attacked again. In a split second, he died in front of my eyes. I survived,” al-Haj said.

“The Egyptian army could not help us or did not want to help us because they were in a truce” with Britain, which then ruled Palestine, he added.

Al-Haj ended up in Gaza. Although the Strip is only 35 kilometers from al-Swafer, he is unable to return to his native village.

Initially, al-Haj lived in a camp set up by American Quakers. In 1950, the UN formed its own agency, UNRWA, to administer camps for Palestine refugees.

Let down

Initially, the camps consisted of tents. These were replaced by cement and brick shelters after refugees froze to death in Gaza City’s Beach refugee camp during the winter of 1951, al-Haj said.

“Life in a camp was not humane at all,” he added. “I knew these tents very well.”

Entire families lived in one tent. Numerous families had to share the same dirty toilets, with no running water.

Al-Haj feels that Palestinians have been let down by international bodies: “The UNRWA officials said, ‘We cannot do everything to good standards because we receive scarce donations.’ They built schools. These schools were not intended to educate the people more than they were intended to prepare the new generation of the Palestinians to work and serve other people.”

Al-Haj still lives in a rented house in Gaza. He has refused to buy a lot of land to build a new house because he never thought that being a refugee in Gaza would be his final destiny.

Sixty-six years after the Nakba, he still dreams of returning to his village.

Wafaa H. Aburahma is a Gaza-based translator. A refugee from the village of Aqer in historic Palestine, she lives in Nuseirat camp in Gaza. She has an English literature degree from the Islamic University of Gaza.