Yedioth Ahronoth 31 May 2003

A watchtower on Israel’s “Separation fence”, in reality a heavily fortified wall with electronic intrusion detection. The wall has been dubbed by critics as “Israel’s Berlin Wall” and “Israel’s Apartheid Wall” (EI/AEF).

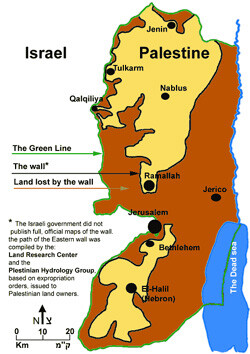

The maps that Sharon’s people asked for were the maps that Prof. Sofer, a geographer at Haifa University and the prophet of “the Arab demographic danger,” presented in a lecture at the Herzliya Conference a few months earlier. Borders should be set immediately for the State of Israel, Sofer said at the time, otherwise the Arabs will inundate us and there will be no Jewish entity here anymore. The West Bank, he explained, must be split into three parts, three cantons, basically three sausages. One sausage from Jenin to Ramallah, a second sausage from Bethlehem to Hebron and a third tiny sausage around the city of Jericho. An electric fence must be put up around these three Palestinian sausages, which extend on less than half the West Bank, and finish the business.

Prof. Sofer and Sharon, then leader of the opposition, conversed at the Herzliya conference. They have not been in constant touch since then, but when Sofer sees the map of the separation fence going up, he smiles to himself. “This is exactly my map,” he says, “it’s as if an exact copy is being put up.”

Sofer takes too much credit for himself. This map is not something new for Sharon. “I haven’t sat with the prime minister recently,” says Ron Nahman, the mayor of Ariel, “but the map of the fence, the sketch of which you see here, is the same map I saw during every visit Arik made here since 1978. He told me he has been thinking about it since 1973.”

There are some who call this plan of Sharon’s “the bantustan plan” (according to Ha’aretz, Sharon used this term when talking to the former prime minister of Italy four years ago), there are those who call it the canton plan. But it is clear that this plan is now taking on concrete and barbed wire. Only now it is called the seamline plan.

Sharon is keeping close tabs on the plan. He comes himself to the site, and sometimes even sketches exactly where the fence is to run. Military sources (the army is the official body responsible for drawing the fence) said recently that every question that comes up goes to the Prime Minister’s Office, to Sharon’s adviser on settler affairs, Uzi Keren, and to Sharon himself. Keren, incidentally, drew up a separation map while a member of the Third Way movement, almost identical to Sharon’s map and to Prof. Sofer’s map.

Something strange has been happening in recent months to the separation fence. What began thanks to a campaign of the Israeli Left and Center under Barak-style slogans of “we are here, they are there,” it has become the baby of the Sharon government. The same Sharon who during the unity government opposed building the fence and was dragged into it almost against his will, on any given day has 500 bulldozers at work, paving and building one of the largest projects in the history of the country, perhaps the largest.

The Bar Lev line, built after the Six-Day War on the banks of the Suez Canal, pales beside the first 150 kilometers of the separation fence, which is to be completed in two months. It certainly pales beside the next 500 kilometers left to complete the project. Even the national water carrier or the draining of the Hula swamps look like an exercise in sandcastles compared to this colossal project.

On the face of it, the logic hasn’t changed: this fence is meant purely to prevent suicide bombers from infiltrating, not to set the country’s borders. In practice, the fence’s course has been changed over and over, each time biting off more of the West Bank. The settlers, who feared that the fence would be made on the Green Line and leave them outside the camp, can be pleased. Judging by the work already done and the Defense Ministry’s maps, for a long time now the fence has not been along the Green Line but is a system of fences that will imprison hundreds of thousands of Palestinians in barbed wire-enclosed enclaves. The first stage of the fence already threatens to make extinct the livelihood of tens of thousands of Palestinians, after the fence swallowed up their land.

Behind the separation fence are thousands of personal tragedies, which are entirely invisible to the Israeli public. Who here cares about farmers like Nimr Ahmed, who in one day lost access to his lands, which he and his fathers had worked for generations. Who cares about a shepherd like Naji Yousef who was forced to sell his sheep because the fence blocked access to pasture. Who is upset that the principal of a high school like Mohammed Shahin of Ras a-Tira, was forced to use donkeys to bring textbooks from Kalkilya since all the roads were blocked by the fence. Who cares about a doctor from Tulkarm who drives five hours every morning from his house to his job in Kalkilya, a distance of 15 kilometers, because he is forced to go by way of Jenin, Nablus, the Jordan Valley, Ramallah and the trans-Samaria road. This kind of occupation perhaps doesn’t kill. Not right away, anyway. But it does destroy the soul.

“The fence is a death sentence for the Palestinians,” says Shmil Elad. Elad is not a peace activist. He is a settler from Einav, deep inside, and his opinions, he says, are “very right wing.” But he mentions the settlement of Salit, next to the villages of a-Ras and Sur. He sees what is now happening to his neighbors, who can’t get to their lands, and it upsets him. “This fence is a mistake, it will only exacerbate the problem, it will make people more frustrated. People here want to work, and you are creating more hatred instead of the possibility of living together.”

A gate is supposed to be built between the village of Sur and the settlement of Salit, enabling the Palestinians to get to their olive trees, but Elad doesn’t believe the gate will be built. Moshe Emanuel, the chairman of the settlement until recently, also doesn’t believe it. “I don’t believe that the army will invest money in some little village,” he says. But Emanuel sees the final goal and justifies it. “In 1948, the Palestinians also lost a lot of land, and in 1967 too. And today they’ll lose again. What can you do, those who lose in war, lose.”

Officially, the Prime Minister’s Office sticks to the original version and says that the course of the seamline barriers is in accordance with “purely security considerations, which are mainly defense against Palestinian terror and preventing harm to Israeli citizens,” and any attempt to attribute other considerations “are purely those of the person asking.” But it is not just the “person asking” who is thinking of other considerations.

“There is a very sneaky combination here,” says the head of the Jordan Valley Council, David Levy. “The army doesn’t look at the political side, it insists on saying that this is a security barrier. But it is clear to everyone that this is a political line behind which there is a political outlook. Those who try and say that the fence doesn’t represent a political line, don’t know what they’re talking about. Don’t give me that nonsense. Everyone is playing this double game, and it’s convenient for everybody. That is why I am in favor of the fence, obviously it will put us inside.”

Levy knows what he is talking about. He says that the chief of staff at first showed him plans that more or less overlapped the old Green Line. “I had words with the chief of staff, I started a world war,” he says. “This got to Sharon and Sharon overruled it. Now the fence will run on the mountain top to the Bekaot intersection.”

Levy relates that he met with Sharon and that the prime minister spread out a map and showed him what the route of the fence would be in his region. He says that according to that map, the fence will keep all of the Jordan Valley and the Judean Desert under Israel’s control, a 20-30 kilometer wide strip. Just as it appears in maps that Sharon has been showing for years, just as it appears in Prof. Sofer’s map. Such a fence, Levy says with satisfaction, is a political statement, a statement of annexing the Jordan Valley under cover of the “security fence.”

But the Jordan Valley is not the end of the story. It will take years until the fence reaches the Jordan Valley. At this time the work is concentrated in the West Bank, the fence that was supposed to be near the Green Line. Already in November 2000, a month and a bit after the Intifada began, the prime minister at the time, Ehud Barak, ordered the construction of a “barrier against vehicles” along the seamline. Sharon inherited the project and appointed Uzi Dayan, the director of the National Security Council to coordinate it, but made him as ineffective as possible. Sharon, like the settlers and the NRP, feared that a fence along the seamline would mean a border along the Green Line. But ultimately, after it was shown almost weekly with what intolerable ease suicide bombers could get into Israeli cities, he too was forced to concede. In April 2002, the security cabinet of the unity government decided to set up a “permanent barrier” along the seamline. Four months later the security cabinet approved the route of the first section, and last August, work began.

Gush Shalom’s map of the wall. Click for more information.

Around 12,000 people in about 13 villages, including large villages like Baka Sharkiya and Bartaa Sharkiya, will be west of the fence, in other words, will be sandwiched between the fence and the Green Line. The fence will separate them from their Palestinian brothers in West Bank and in order to go to Jenin to buy something or sell something, they will have to pass a border crossing, which is unclear when and where it will be. It is also not clear how they will receive basic services such as schools or health services from the PA, which will be on the other side of the fence. While there will be no fence between them and Israel, in Israel they will be considered illegal residents, and there is no intention to annex them or turn them into Israeli citizens.

But this is only part of the story according to the same report, which is based also on a detailed report by B’Tselem. More than 30,000 Palestinians are liable to completely lose their livelihood because their lands are on the “Israeli” side of the fence. This is the most fertile part of the West Bank with almost 40% of the agricultural land of the West Bank. In the Jenin, Tulkarm and Kalkilya districts - the districts in which the work on the first stage is being done - around a quarter of the residents work in farming, more than twice the percentage in the rest of the West Bank. One square kilometer (10,000 dunam) of farmland in these areas produces income of about USD 900,000, more than twice the income from a similar area in the rest of Judea and Samaria. Around two thirds of the water sources in the West Bank are also in this area. 28 wells will be west of the fence, and it is unclear what will become of them. In short, a blow to agriculture in Jenin, Tulkarm and Kalkilya is a blow to all the Palestinians in the territories. According to the World Bank report, the first stage of the fence will affect the livelihood of over 200,000 Palestinians.

The village of Jawis, situated more or less opposite Kochav Yair, numbers around 3,000 people. Before the Intifada, many of the men worked in Israel. Now, obviously, this is all over, and many have gone back to farming. More than half of the breadwinners in the village work the land. Or more correctly, used to. The route of the separation fence flanks the last houses of the village and 9,000 dunam of farm land, almost all of the village’s lands, will remain west of the fence, in the side close to Israel.

A short walk from the outer homes of the village, not more than 200 meters, leads suddenly to the edge of a cliff. The view here is marvelous, the air fresh. Below one’s feet is the coastal plain, from Kfar Saba to the sea. The Green Line is discernible with the naked eye. At one point in the plain, relatively far (six kilometers separate the village from the old border) the small and crowded farming plots of the Palestinian are replaced by the open fields of the kibbutzim and moshavim in Israel. You look a bit more and suddenly realize that this cliff, more than 100 meters high, is the work of man. The work of the fence builders.

The hill was cut in the middle, and the route of the fence is paved beneath it. The word “fence” is too paltry to describe the matter. On the eastern side, the Palestinian side, there is barbed wire, then a deep ditch, then a dirt road, then the fence itself, eight meters high, and then another dirt road, then an asphalt road (“wide enough for a tank,” the Defense Ministry explains to me later), and then more barbed wire. You have to be almost insane to think that somebody uprooted mountains, leveled hills and poured billions here in order to build some temporary security barrier “until the permanent borders are decided.”

From the hill where the village sits, one can see the tomato, cucumber and flower hothouses, the citrus orchards, which remain beyond the barrier. A narrow dirt road, suitable only for donkeys, links the village to its lands, crosses the route of the fence, which is still incomplete in this section. And what will happen the moment the fence is completed? Nobody knows.

After work was begun on the fence nine months ago, the army promised, in a reply to the High Court of Justice, that “agricultural gates” would be inserted in the fence, enabling people and farming vehicles to reach their land. Will such a gate be made in Jawis? Villagers relate that they tried to talk with the army commanders in the area, and received no answer. In the meantime, few dare to cross the route of the fence and risk being shot by the security companies guarding the work to reach their fields. One thing is clear to all of them: if there is no access to the fields, this village will effectively remain without a source of livelihood. And another thing is clear to all of them: the chance of them having access to their fields through the fence is very small, almost nil.

The situation is similar in the nearby village of a-Ras. Eid Yassin, the village leader, has, together with his brother Nimr, 120 dunam of olives and almonds, 110 of them beyond the fence. “Soldiers came, and didn’t let us approach,” Nimr Yassin relates. “We asked the commander if we could go to our land and he said: yes, no, I don’t know. Now we sneak over to our land like smugglers. Sometimes they shoot at us, sometimes we manage to get there. Our olives have dried up.”

Eid Yassin says that the fence has also cut off the road to Tulkarm, the local district town, creating a very difficult problem for the village. There is no clinic in a-Ras, or high school. For all this they need to go to Tulkarm. What will they do now? Naji Yousef, another villager, relates that he doesn’t feel safe even in his own home. His house is close to the fence route, and his wife went on the roof to hang up laundry, and soldiers shouted to her to get down. “If you go up there again, we’ll shoot you,” they told her, he says. When the fence is under your nose, even hanging up laundry is a security risk.

Many Palestinians say that behind the building of the fence is the desire to steal their land. Attorney Azzam Bishara of the Kaanun organization, who represented landowners in petitions to the High Court of Justice against the fence, mentions the Ottoman land law, which everybody in the territories can declaim by heart. According to that law, which is still valid in the territories, “miri” type lands are given to the farmers to work, and they are allowed to hand them down from generation to generation, but they continue to belong to the sultan, and the fallah is not allowed to register them legally in his mane. If the fallah does not work the land for three years running, they revert to the sultan. Israel considers itself the successor to the sultan in the territories, and by exploiting this law, much land in Judea and Samaria was declared state land, after aerial photographs proved that the lands were not worked for three years or more. Most of the settlements were established on such lands. Now all the Palestinian fallahin are convinced that Israel will not let them have access to their land for three years and will then declare them state land, and they will lose them forever.

This is not oriental fantasy. “The Palestinians’ fears are not unfounded,” says Uzi Dayan, “but their fears are no greater than the fears of the residents of Tzur Yigal.” This sentence embodies the gist of the concept of the first people to come up with the idea of a fence.

Dayan, who has since resigned, believed in the separation fence project from the first minute, and he still believes in it with all his heart. Before leaving the National Security Council in June 2002, Dayan presented a report to the prime minister in which he wrote that Israel must build itself a border “according to demographic principles.” In other words, a fence that will provide as much security as possible and include as few Palestinians as possible. The monetary outlay, now estimated at over NIS six billion, is secondary in his eyes. The loss to the Israeli GNP as a result of terror attacks is much greater. A fence, he says, is worth it.

Since he began working on it, Dayan supported moving the fence east of the Green Line. There is an obvious security reason for this. If a terrorist nevertheless manages to cross the fence, explains Netzah Mashiah, director of the seamline administration in the Defense Ministry and today responsible for getting this enormous project off the ground, the security forces need additional response time before this terrorist reaches the homes of some Israeli community. But along with this reason there are also political reasons. The moment the work began on the fence last August, everyone understood that this was to be the new border, and those who don’t board the train now, would miss it. Even Uzi Dayan said: “The Green Line is not sacred. There are places where more territory should be included, thinking in the long term.”

The settlers, who realized that if they did not support the fence, would lose the public’s support, shifted their activities to lobbying to include as many settlements as possible to inside the fence. Ben-Eliezer, who to this day continues to contend, “the fence has no political purpose and those who say otherwise are wrong,” is almost alone in this claim. Even Netzah Mashiah, the guy building the “security” fence, says: “The politicians found a formula, but I believe the fence will be the border.”

An excellent example of the fact that the fence can be flexible is Alfei Menashe - an established settlement of 5,000 residents, five kilometers east of Kalkilya, which at first was to be outside the fence. This was very much not to the liking of Eliezer Hasdai, head of the local council and member of the Likud Central Committee. “According to the first plan,” he says, “the fence was supposed to be close to the Green Line. I undertook a great deal of political activity, Sharon and Fuad came to visit me and agreed to put Alfei Menashe inside and to ‘wrap’ the fence around it.” But Hasdai didn’t like this solution either. “The way it was, after leaving the gate, I would enter Palestinian territory in Habla 200 meters later and only come out at the fruit junction.”

Help came from an unexpected direction. According to the Defense Ministry plan, a new road was to link Alfei Menashe to the Green Line in the area of Matan, a community between Kfar Saba and Rosh Haayin. Matan residents feared that this road would block their view. So while Hasdai was being active in the Likud, Matan residents were taking action in the Labor Party. “Kalkilya must be cut off from Habla,” they wrote in a letter to the Labor Party Central Committee, which met at the end of August 2002 to discuss the separation fence. “Kalkilya, the largest terror nest in the heart of the Sharon, must not be made a large city with 100,000 residents,” Matan residents added. The numbers were twice the actual fact, but the pressure worked.

[NEXT…]