The Electronic Intifada 17 August 2022

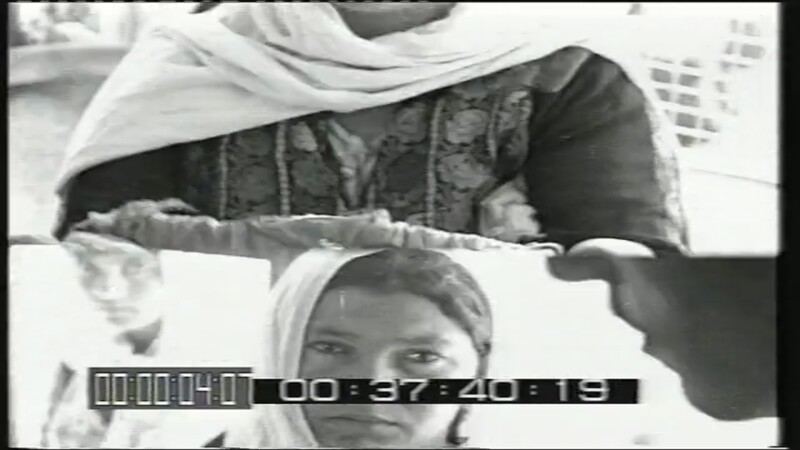

A frame from footage recorded by Palestinian revolutionary filmmakers and included in A Reel War: Shalal.

Israel’s looting of Palestinian cultural and historical archives since the first half of the 20th century has been exposed and discussed for only around the past two decades.

In 2017, I directed a film essay titled Looted and Hidden: Palestinian Archives in Israel that deals with the Palestinian cultural archives confiscated by Israel during its invasion of Lebanon in the 1980s.

In this film, as well as in articles and books I have published on this topic since 2000, I discuss how Jewish and Israeli military forces, as well as individuals – off-duty soldiers and civilians – have taken possession of Palestinian cultural materials throughout the 20th century and to this day.

As far as I discovered in my research, these materials include photographs, films, exhibitions, books, manuscripts, embroidered garments, graphic arts, music and more.

The seized Palestinian archives, collections and materials – cultural and otherwise – were typically surveyed and studied by Israeli intelligence and transferred to the pre-state and state’s colonial archives, both military and civilian. In many cases, Palestinian cultural property looted by individuals was also put in Israel’s official archives.

An archive serving to preserve historical memory would catalog the context, origin, purpose and authors of the materials, all of which would be easy to glean in the case of these materials seized by Israel.

Israel’s purpose, however, is not to preserve Palestinian historical memory but to erase it from the public sphere. Therefore, Palestinian materials are not catalogued and treated according to archival standards and conventions but are instead subjected to colonial ones.

Control

The seizure of Palestinian cultural materials does not stop with the physical act of confiscation. Israel hides the materials in its archives, limiting access and preventing their exposure. Israel meanwhile classifies materials in an inaccurate and biased manner that suits the Zionist narrative.

For example, the materials looted from Beirut are listed in Israel’s military archives as the “PLO archive” – a body that never existed.

My studies of the archive’s bureaucracy reveal the destructive colonial means by which Israel exerts control over Palestinian narrative and history.

My goal has been to give this issue the exposure it deserves so that seized and looted cultural and archival materials are returned to their Palestinian owners and restored to the public sphere.

I am aware of the problems inherent to my work. Because the Israeli archive holds Palestinian materials by force, Palestinians face limitations to access. It is true that I have fought to open the archives and have partly succeeded in doing so. But I can do this only because I am Israeli.

Some individual Israelis are directly responsible for the looting of Palestinian materials in wartime and during military operations. But Israeli society as a whole is implicated.

Elimination

Erasure is central to Israeli apartheid and citizens including artists, creators and film directors (not just the military, politicians and archivists) play a role in the colonial process of elimination of the Palestinian past.

The 2018 exhibition Stolen Arab Art at Tel Aviv’s Center for Art and Politics included screenings of video works by famous Arab artists without their consent, knowing permission would be denied due to the cultural boycott of Israel. The exhibition was thus widely condemned within the Israeli art world.

This is hardly the only case of Israelis using Palestinian cultural materials without their authors’ permission, thereby replicating colonial methods of erasure and control.

While Stolen Arab Art forthrightly indicated that the display violated the creators’ rights, the 2021 documentary A Reel War: Shalal by Karnit Mandel misleadingly implies that footage by Palestinian revolutionary filmmakers was included with the permission of its owners.

In A Reel War Mandel “discovers” where the films were taken from – much of the relevant information is in the credits of the films, so the supposed discovery is relatively minor – but does not bother to interview their creators or their families.

Mandel’s film emerges as another colonial act in the ongoing destructive movement against Palestinian culture and history.

Mandel sought permission to use material from Sabri Jiryis, the last director of the Palestine Research Center, established in 1965 while it was still based in Beirut. Academic in nature, it was founded to document and research Palestinian history, and to publish books and articles devoted to the subject.

Whether Jiryis has authority to grant such permission is not addressed in the film.

The principal doubt – how does one ask permission from someone that does not have the authority to give such permission – does not come up.

I recently contacted Israeli state archivist Ruti Abramovitz to ask her how materials were used in Reel War without the permission of their owners and when the films and other seized materials will be returned to their rightful owners.

Her official reply? “I am not going to respond.”

In January, I lodged a formal complaint with Israel’s state comptroller. I contended that state archivists violate the rights of the owners of seized Palestinian cultural materials.

I also asked for an investigation into why Israel holds the materials and when the seized cultural property will be repatriated.

I was told in a phone call two months later that the state comptroller is not obliged to reply to the complaint.

There is at least one precedent of Israel returning an archive to its Palestinian owner: that of the Jerusalemite photographer Ali Za’rur.

Although this archive was not looted or seized but given as a gift to the mayor of Jerusalem by a member of the family, I hope this will serve as a precedent to repatriate archives captured and held in sin.

Dr. Rona Sela is a researcher of visual history, a curator and film director and a lecturer at Tel Aviv University. An earlier version of this article was published in Hebrew in Siha Mekomit.