The Electronic Intifada 24 February 2015

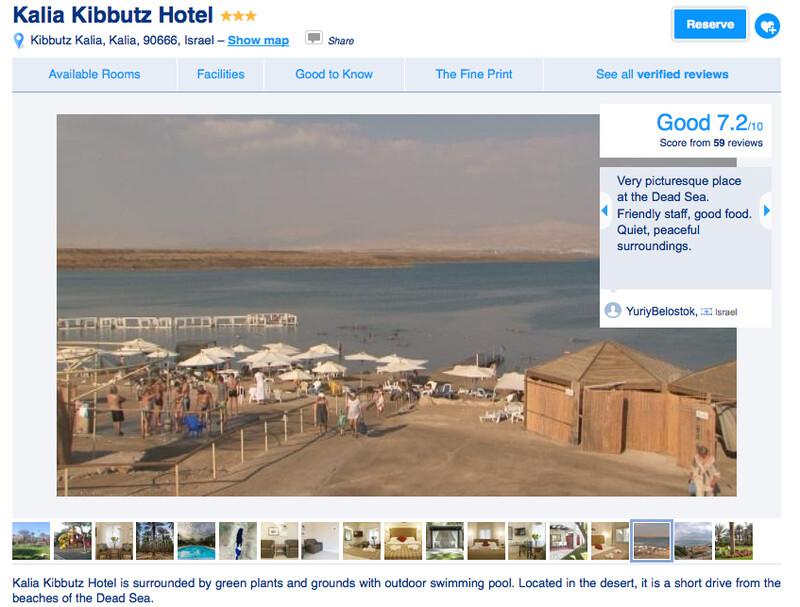

Booking.com’s listing for Kalia Kibbutz Hotel makes no disclaimer that it is located in a West Bank settlement.

I travel frequently to Palestine. Usually, I avoid tourist attractions but last year I decided to make a short trip to the Dead Sea. Searching for a place to stay, I checked the travel website Booking.com.

Immediately, I felt uneasy. Could some of the hotels it had listed be located in Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank?

Rather than making a reservation, I drove to one of these hotels. Although the address given for the Kalia Kibbutz Hotel on Booking.com indicates that it is inside present-day Israel, the truth is quite different. It can be found within Kalia, a settlement in the West Bank that is one of the main shareholders in the cosmetics company Ahava.

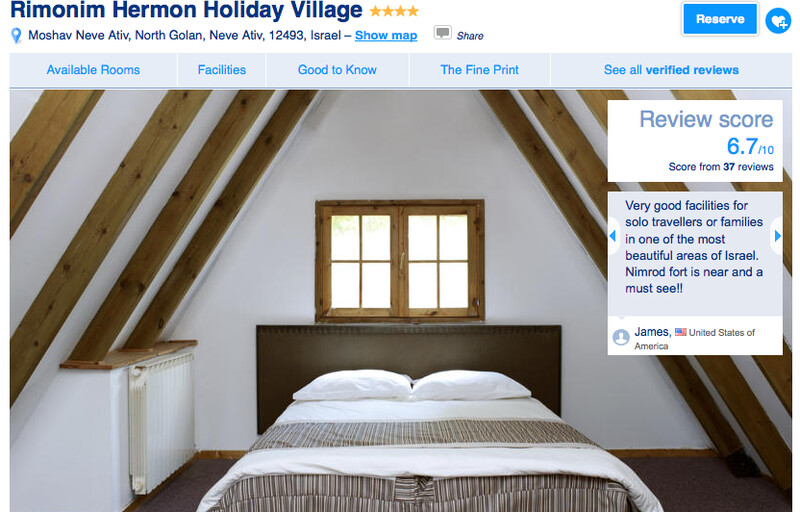

The Rimonim Hermon Holiday Village is described as located in Israel rather than occupied Syria.

The settlement is located within a gated village. This means that Palestinians are forbidden from entering. The hotel had few guests when I called. But the deceptive details on Booking.com could easily lead unsuspecting tourists to think they are staying inside Israel, when in reality they are in an illegal colony.

All of Israel’s settlements in the West Bank violate the Fourth Geneva Convention, which forbid an occupying power from transferring its civilian population into the territory that it occupies. The construction and upkeep of these settlements, therefore, amount to war crimes.

By advertising hotels in these settlements, Booking.com is abetting war crimes.

The Kalia hotel is by no means unique. Booking.com offers tourist accommodation in settlements that Israel has built on Palestinian and Syrian territories it has occupied since 1967. They include the Olive Tree Hotel, an Israeli hotel in East Jerusalem, apartments in Kfar Adumim, a settlement in the West Bank and the Rimonim Hermon Holiday Village in Syria’s Golan Heights.

False claim

Earlier this month, I contacted Booking.com, asking if the company was aware that it was offering customers the possibility to stay in illegal settlements.

André Manning, a representative of the firm, replied: “We try to follow the demand of our customers and try to accommodate them as best as possible across the globe.”

“Generally for any property that’s located in the West Bank area, we indicate clearly whether it is in Palestinian territory or part of Israel — whether or not you call this illegal, disputed, unrecognized, which is not up to us,” the firm added.

Booking.com gives an address for Tekoa Lodge in Israel rather than the occupied West Bank.

That claim is patently false. The Tekoa Lodge is located in a settlement built illegally in the occupied West Bank. Yet the address given for the lodge on Booking.com says it is in Israel.

Booking.com was founded in the Netherlands during the 1990s. Although it was taken over by the US firm Priceline in 2005, it remains headquartered in Amsterdam. Today, it is Europe’s most popular accommodation website.

It may not be up to the firm to determine if the West Bank is occupied in an “illegal” or merely “disputed” manner. Yet as a firm based in the Netherlands, Booking.com ought to pay attention to guidance given by the Dutch government.

Double standards

Frans Timmermans, the former Dutch foreign minister, has repeatedly warned Dutch firms against investing in Israeli settlements in the West Bank. Timmermans, who recently became a European Union commissioner, stated in 2013 that the territories seized in 1967 “don’t belong to Israel.”

Similarly, “guiding principles on business and human rights” published by the United Nations in 2011 require firms to respect international law, including the Fourth Geneva Convention.

It is significant that Booking.com has been willing to follow advice from official policymakers on its activities elsewhere.

Last year, the firm reportedly asked hotels in Ukraine if they had any connections to Viktor Yanukovych, who had been removed from power as the country’s president in February 2014, and seventeen other individuals against whom the European Union had introduced sanctions.

Anoeska Van Leeuwen, a representative of Booking.com, was quoted in The Moscow Times saying that “as a Dutch company, we fall under the trade restrictions of the EU.”

The double standards at play here are breathtaking. Booking.com responds quickly when trade restrictions are imposed on political figures perceived as hostile to the West. Yet it appears untroubled by how it abets war crimes if those crimes are perpetrated by Israel.

Mieke Zagt is a human rights activist and Middle East specialist based in the Netherlands.