The Electronic Intifada 6 July 2009

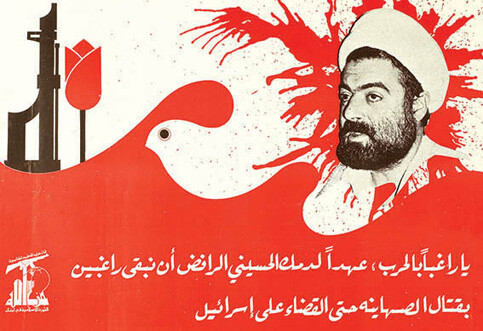

A poster commemorating the second anniversary of the assassination of Sheikh Ragheb Harb, by Merhi Merhi, 1986 (Hizballah Media Office)

Author Christopher Hitchens might have saved himself a beating had he read Zeina Maasri’s book Off the Wall: Political Posters of the Lebanese Civil War. Hitchens, a self-proclaimed expert on all matters theological and Middle Eastern, was attacked in the streets of Beirut last February after defacing a political poster. The power of posters apparently touched Hitchens himself, who felt compelled to express his vindictiveness by attacking an image. But in a war-ravaged place like Lebanon, images can be a lot more than mere symbols. As Fawwaz Traboulsi explains in Off the Wall’s forward, they can serve as weapons, and Hitchens’ attackers must have understood that quite well.

The power of posters, as not merely symbolic weapons but also sites of hegemonic struggle during Lebanon’s civil war, is a central theme of Maasri’s book. A mix of text and image, the book is a rich and visually engaging work that tackles a dimension of war long-neglected by Lebanese historians. A sample of 150 posters (out of 700 the author has examined) in full color and printed on laminated paper occupies the center of the book and it is hard to begin reading before going through them: portraits of “heroic” leaders of all factions, clenched fists facing enemy guns, silhouettes of martyrs and landscapes of religious and nationalist symbols overlooked by dominant war figures, many marked with slogans that range from the racist to the revolutionary. But the book is a lot more than a slideshow of images summing up defining moments of the war or a straightforward critical review of the posters. Maasri delves into questions of theory, representation and meaning that shaped and defined the art of poster-making and the politics of their interpretation during times of conflict.

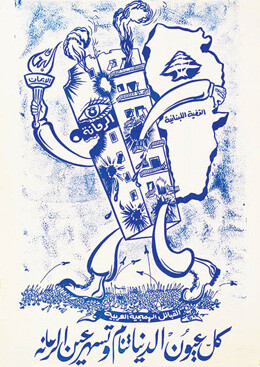

“The world is asleep while Ain el-Rummaneh stays awake,” anonymous, c. 1978-79 (American University of Beirut Library)

The book picks up pace as Maasri delves into more concrete analysis of the posters themselves and the people behind them. Stories of political cartoonists and graphic designers who became prominent are told and their work decoded in terms of style and content. Some readers might take issue with her uncritical evaluation of the work of prominent cartoonist Pierre Sadek who was a staunch supporter of right-wing militia leader Bashir Gemayel. In one instance, Maasri speaks of the straightforward symbolism of Sadek but in another laments the absence of the “subtleties” of his work in the work of fellow right-wing artists. Despite Maasri’s articulate depiction of the political context of the posters for most factions, when speaking of Sadek’s work, she skips over one major context that defined the faction Sadek cheered for, namely the alliance between Israel and the Lebanese Phalange party, including the direct role Zionism played in “electing” Gemayel as president. Unlike the explicit exploration of the impact the alliance between Hizballah and Iran had on poster-making of the former, the links between Zionism as a racist ideology and the Phalange is reserved for the final section of the book.

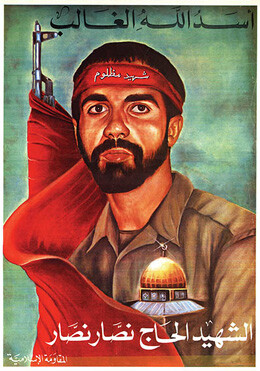

“God’s victorious Lion. The martyr Hajj Nassar Nassar,” by Adel Selman, c. 1980s (Hizballah Media Office)

The variation in ideological motivations of different movements translates into a multiplicity of collective identities expressed in the art of poster-making. Maasri explores the controversial question of belonging in Lebanon as the fourth theme of posters. She describes the polarity of “we vs. them” in civil war posters and how the enemy is manufactured and its identity consolidated through the language of imagery and rhetoric. Dehumanizing the enemy as a ruthless and inferior aggressor appears strongly in the works of the right-wing Lebanese Front that was formed in the ’70s. In one poster sympathetic to the Lebanese Front, a giant war-torn building carrying a Lebanese map is stepping over a mass of ant-like people identified as the “barbaric Arab tribes.” Questions of belonging are not only in relation to the other, but also to the collective self. From communal resistance to a nationalistic sectarian consciousness to the bond between people and land, belonging takes on shifting and contested meanings for different communities and different struggles, something that illustrates Maasri’s initial argument about posters as sites of hegemonic struggle. As such, Maasri’s work becomes all the more relevant today, amid an explosion in the production of political posters across Lebanon that hasn’t been witnessed since the official end of the civil war in the early ’90s. A quick comparison between the posters in the book and contemporary ones plastered across the walls of the country brings out both continuities and discontinuities in terms of themes and style. Still it is hard not to notice that form and presentation today overshadow content, with slogans today adopting advertising style and increasingly lacking the intensity and urgency of those during the civil war. Who knows what would have befallen Hitchens had he attacked the poster all the way back then.

Hicham Safieddine is a Lebanese Canadian journalist.

Related Links