The Electronic Intifada 10 June 2004

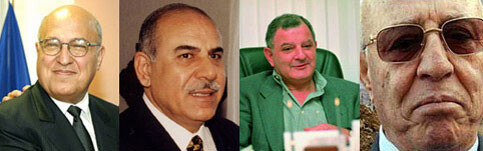

Nabil Shaath, Jamil Tarifi, Maher al-Masri and Prime Minister Ahmad Qurei

Seven years ago, a Palestinian parliamentary panel conducted an investigation of the PA corruption. The nine-member panel of the Palestinian Legislative Council had, at the time, acted upon the Palestinian State Controller’s report that found that nearly half of the authority’s $326 million 1997 budget had been lost through corruption or financial mismanagement. The report of the PLC’s Monitoring Committee exposed many official misgivings and abuses.

The report was based on a former report by the Auditor’s Office, which revealed a misuse of funds amounting to more than US$326 million, that is, 43 percent of the 1996 budget. Of this budget 35 percent was spent on security forces and 12.5 percent of the budget went to the Office of the President, which left only 9.5 percent of the budget for public allocation. It made certain recommendations and demanded action to correct these ills but they were not adhered to.

At that time the international community didn’t pay much attention yet. Although corruption has been long on the Palestinian domestic agenda, to the outside world it was until recently not considered of primary importance. At the time, those critical of corruption were also those who opposed the Oslo process.

Only recently began the EU and the US to focus on Palestinian reform, mostly as a result of President Bush’s speech on June 24, 2002 and the announcement of Arafat’s 100-day reform plan two days later. The 100-day plan called for reforms in ministries, institutions and security apparatuses, as well as in the ministry of finance and the judiciary. Donor countries formed a taskforce to work directly with the Palestinian Authority on reform.

The United States and the European Union did not begin to discuss Palestinian reform until well into the current Intifada, when they realized that the current Palestinian regime had lost control over radical factions and the security situation had dramatically worsened. It became in the Western and the Israeli interest to promote reform for the purpose of spurring the Palestinian leadership “to curb terrorism,” even if this required a change of leadership. However, reform in this context meant security reform and not the reform demanded in 1996, meaning accountability, transparency, parliamentary oversight and rule of law.

In 1997, a specialized committee decided that a new Palestinian government should have been formed and anyone found to be involved in the corruption scandal should be taken to court, irrespective of whether he was a minister, undersecretary or director-general.

The report stated that “the committee recommends to the president of the Palestinian Authority to dissolve the cabinet and form a new one made up of technocrats and qualified people”. It recommended that Civil Affairs Minister Jamil al-Tarifi, Planning and International Cooperation Minister Nabil Sha’th, and Transport Minister Ali Kawasmeh be brought to trial.

Over six years since, Tarifi is still in the Cabinet and once more subject to parliamentary investigation for corruption. Shaath has never left the Cabinet and his position has been steadily advancing.

Cement Gate

Yesterday, the Palestinian Legislative Council held a debate in which Minister of Economy Maher Masri was accused of negligence and fraude. Members of the Council called for an investigation into allegations that Palestinian companies had been importing cement from Egypt for Israeli companies.

One of the PA officials involved in the case is PA Civilian Affairs Minister Jamil Tarifi, whose family owns the Kandil Tarifi Cement Factory, one of the biggest in the West Bank. Two other companies involved in the scandal are Intisar Barakeh Company for General Trade and Yusef Barakeh Company for General Trade.

Minister Masri admitted that some companies which had received import licenses from the Ministry of Economy had violated the law. He said he took measures to ensure that the transactions were stopped. He announced that all those involved in the scandal would be prosecuted. The scandal erupted following reports in the media that two Egyptian cement companies were exporting material to Israeli firms through Palestinian businessmen.

Legislators Hassan Khraisheh, Sa’di al-Kranz, and Jamal Shati visited Jordan and interviewed the owners of the companies. They spoke with Jamil Tarifi, Maher Masri, Prime Minister Ahmad Qurei, Arafat’s economic advisor Mohammad Rashid and other PA officials. The panel found that a German businessman imported on behalf of Israeli companies some 120,000 tons of cement from an Egyptian cement company. When the Egyptians found that the cement was imported to Israel they ordered the company to cut off its ties with the German company.

The inquiry committee said that the German businessman found assistance from Palestinian companies that were ready to act as intermediaries. Several senior PA officials received bribes to issue licenses to several compnaies working on behalf of Israeli companies. Hassan Khraisheh, a member of the PLC team that investigated the case, said the entire cabinet should be held responsible for the corruption scandal.

The Prime Minister, Cement and Channel 10

The inquiry committee was investigating whether a cement company owned by Prime Minister Ahmad Qurei’s family had been selling cement to Israeli settlements. On 11 February, Israeli Channel 10 TV reported that the Al-Quds Cement Company was providing the materials to help build Israel’s Apartheid Wall. Television footage also showed cement mixers leaving the Al-Quds company and driving to the Jewish settlement of Maale Adumim, just a few kilometres away. Qurei denied the claims. “I invite you and I invite the people who said this to come and check on the ground,” Qurei told reporters after a meeting in Rome with Italian Foreign Minister Franco Frattini.

The previous inquiry reports recommended that “the president of the Authority should issue his instructions to punish violators against whom there has been evidence of guilt and to punish them immediately and to take them to court in order to restore confidence between the Palestinian Authority and its people”. None of these officials were put on trial. Responding to the reports in 1997, the PLC voted 51-1 in favor of dissolving Arafat’s appointed 18-member limited self-rule cabinet.

Soon after its publication in 1997, sixteen ministers gave letters to the president signaling their readiness to resign if he wished. Additionally, PLC-member Haider Abdel-Shafi resigned due to “frustration with the performance of the PLC and with the executive’s total lack of concern for its recommendations”, and added “that the PLC is a marginal body and not a true parliament”. In the meantime, even as the PLC committee was conducting its investigation, the president appointed Tayeb Abd al-Rahim, General Secretary of the Presidential Office, to make a detailed inquiry into acts of corruption. The result has been yet another (secret) report. There are, then, three studies of corruption. The executive and the president refused to deal with the report of the PLC and ignored its recommendations. This case exposed the PLC in all its impotence.

The current “cement scandal” will now be referred to the Palestinian attorney-general. No evidence was found that the cement was used in the construction of Israel’s Separation Barrier but in construction of Israeli settlers’ units in the occupied Palestinian territory.