United States 26 January 2009

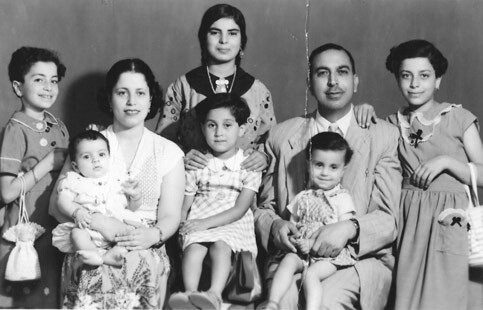

The author’s grandparents and their children in Baghdad in 1955.

I have never seen my grandmother without a large medallion hanging from her neck. As a child, I stared at the pendant’s engraving of a gold-domed structure, watched the turquoise walls glimmer as they caught light from the piercing Iraqi sun. When I asked Tata what the pendant depicted, she replied, “The place where I’m from.” I thought of it as a palace towering in a far, mythic land, like the great emerald castle of Oz.

I later understood that it was the Dome of the Rock, located at the heart of Jerusalem’s Old City. The city, a religious and at times economic and cultural hub of a predominately Arab Palestine for nearly 1,200 years, has been in modern times, hotly contested with the establishment of the State of Israel on Palestinian soil in 1948. With the birth of the Zionist state, came the destruction of Palestinian society, and Tata was forced to flee her home along with more than 700,000 other Palestinians. When I finally understood the pendant’s historical context, I realized that for Tata, it symbolized a land that she treasured but could not return to, an emblem of both beauty and tragedy.

As years passed, the medallion became lackluster, its once glimmering surface now dull, corroded by decades of wind and sand. No longer charming the sun’s light, it became an unassuming feature on Tata’s body, like a scar on a friend’s face that one used to discreetly examine but now rarely notices. I overlooked the pendant and overlooked Tata’s experience. But like a scar whose origin has gone unpronounced, the desire for discovery lingers until it is fulfilled. The year 2008 began, marking the 60th anniversary of the Nakba, the forced expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland. Across the world, people celebrated Israel’s “Independence Day.” Others remembered the lives of the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians killed or displaced in its wake and the nearly four million Palestinians still living under the Israeli military occupation of the West Bank and the brutal siege of the Gaza Strip, and the population of five million Palestinian refugees that have yet to see their right of return realized. On this memorable anniversary, and the year of Tata’s 80th birthday, I asked her for the first time, “What was it like for you?”

Tata clasped the pendant and smiled. “Let me tell you about Palestine, the way it used to be,” she said in Arabic. “The thing I’ll remember most is my childhood in the city of Jaffa. Every day we would go to the beach and play in the sand. It was just one block from our home, the apartment building that my father owned. At night we would sit on the balcony and watch the big ships sail by, listening to them whistle.” Tata laughed. “We ate so many oranges! They called them ‘the yellow gold.’ My uncles worked as orange merchants. They would bring big bags to our house. I would pile up ten, 11 oranges in my lap and eat them all at once.”

She also told me about the hardships of being a girl in the 1930s. “When I was in seventh grade, my father heard a sermon at the mosque that girls should not be too educated. The imam said that it’s enough for girls to be able to read and write. So my father pulled me out of school at the age of 12.”

Tata’s voice softened. “I had been very happy in school. I loved learning and spending time with my friends. So I was very upset when I couldn’t go anymore. I cried a lot. I would see my friends through the window walking to school, see them walking happily without me, and I’d cry.”

As Tata began to talk about her marriage, her tears dried and her honey-colored eyes sparkled with girlhood excitement. “At first they said he was too old for me. But then they said it was fine. He was a principal of a school in a nearby village. When we first moved into our house in the village, I couldn’t believe how big it was. My friends would come visit me while your grandfather was at work and we would jump rope together in the middle of the living room.”

Soon, Tata was no longer smiling as she began to tell me about the political situation that existed in Palestine during her childhood. “When I was a child, I heard all about the Jews that were immigrating little by little to Palestine, especially Tel Aviv, which was close by us. We knew they wanted our land, but they weren’t very powerful. We didn’t pay much attention to it.”

“I remember hearing about Balfour, though,” Tata continued, “The British wrote this declaration [in 1917] which said that Jews needed their own homeland in Palestine. Palestinians didn’t agree. It was our land, why should we divide it?” Tata sighed, “Then it began.”

“We were hearing about Jews raiding Palestinian towns. My brother bought a pistol for self-defense, in case there was a raid. The Palestinian resistance began. There was a four month general strike [in 1936] throughout Palestine to protest. No one went to work. My father would stay home all day.” This has come to be known as the Arab Revolt in Palestine, which was concentrated in the years 1936 to 1939. The nearly 10,000 Arab fighters and Palestinian society at large demanded an end to the British Mandate, which helped facilitate Zionist immigration and settlement of the land. Zionist paramilitary organizations and British forces stifled the revolt and 120 Arabs were sentenced to death, my grandfather among them. Though he was tortured in captivity, he was luckily able to narrowly avoid execution.

“At this time [1947-1948] we were still hopeful. Arab forces came from all over to fight for Palestine. At the same time, huge ships came in full of Jewish people immigrating to Palestine. I saw them getting off the boats at the docks.”

“Then the massacres of villages began. There were three villages by Jaffa that were massacred. Deir Yassin was the one that led us to leave. It was a Friday and men were all out praying at the mosque. The Jewish forces entered the houses and killed children and their mothers. They threw them in wells and killed children while they were in their mother’s laps. [Your grandfather] came home. He had heard about the massacres. He said ‘that’s it, we can’t stay anymore.’ He heard about the women being raped and that was the last straw.”

“At first we moved to an apartment further away from the bay. We thought this would be safer. Everyone else in our building left too. But we didn’t want to leave Palestine for good. We thought the Arab forces would come and save us. Your grandfather was asked to give news on a radio station run by Arab troops. He did this for some time, trying to convince people not to leave our country, to stay and fight.”

“There were bombings during that time. I used to look outside the window and see explosions coming from all directions. My daughters, one four years old, the other two years old, were very scared.”

“Because of the situation, we decided it would be best for our daughters if we moved further away from the fighting, to Nablus, for some time. This was in the early summer of 1948. All we took with us were some clothes, a roll up mattress, a small carpet, a prayer rug, a few kitchen supplies, and some books. We only had 80 Jordanian dinars with us. We left our furniture because we were worried it would break on the way. We left our diplomas. We thought, ‘we’ll back in three months or so.’ We thought by then the Zionists would be defeated. When we left, we left everything.”

“In Nablus we lived in a tiny apartment. There was only one room for all of us to sleep in, a small kitchen, and a bathroom. We didn’t have any furniture, so we piled up our things on the floor against the walls.”

“We wanted the Arab troops to fight so we could return to our home in Jaffa and return to our lives. We saw Arab troops around and we would ask them, ‘Why are you here? Why aren’t you fighting?’ They responded, ‘We don’t have the orders to fight.’ We would see Arab troops spending their whole days at the public baths, so we used to have a rhyme that went ‘There aren’t orders for the battlefield, but there are orders for the bath.’” Tata smiles briefly then adds soberly, “We realized this wouldn’t be over quickly.”

“We stayed for two months in Nablus. We decided for our family’s safety, for our daughters, we had to leave the country until we got it back. Your grandfather was working for an English pharmaceutical company called Evans, in the advertising department. They had a branch in Baghdad too. He arranged to transfer his position to Baghdad. He had a friend in Iraq in the Foreign Ministry, a man who sent him translated articles for free gave us Iraqi passports. So we tied all of our things up on the top of a taxi and drove to Amman. It was very expensive, it cost us 40 dinars. From Amman we went to Baghdad.”

“On our way to Baghdad we saw many pick up trucks with Palestinian refugees in the back. They were coming from villages that had been massacred or destroyed, taken by Iraqi troops to Baghdad. They traveled all that way under the hot sun, with nothing above them to provide shade. I would see them throwing up out of the back of the trucks, getting sick from the heat. They were taken to ‘Tobchee,’ a neighborhood with government housing, and received assistance from the Iraqi government.” Tata explained that these refugees, the ones that were able to resettle in Iraq, were the lucky ones.

Many Palestinians ended up in refugee camps in squalid circumstances, both “internally” in what came to be known as the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and externally in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Many Palestinian refugees faced hostility from their government hosts, but in some countries such as Lebanon, they held and still hold practically no rights amid systematic policies of discrimination towards refugees.

Tata begins to describe the hardships her family faced as refugees in a foreign country. “At first, when we got to Baghdad, we stayed in the best hotel. It was paid for by Evans. But after that, things didn’t work out with their branch in Baghdad. They paid your grandfather two months salary then let him go. We were very worried. But he heard from other Palestinians that Arab Bank was opening a branch in Baghdad. He got a job there as a teller for a very low wage. His manager loaned him money to support his family. Eventually he was promoted to be a manager.”

“Your grandfather started working as a translator as well, translating books and articles from English to Arabic. He was always working. He worked two or three jobs to support us all. He got very sick. He was tired all the time and complained of pain, but he still had to work.” Tata explained that he grew up as a farmer in a small Palestinian village, Budrus, and spent his entire life engaged in relentless hard work in an attempt to advance his family’s circumstances.

Upon visiting Budrus in 2006, I was told stories of my grandfather’s determination for advancement. He used to place his feet in a pot of icy water, I was told, to keep himself alert as he studied. He used to stand on a chair with his head in a noose that hung from the ceiling while he studied through the night, motivating himself not fall asleep. “He was a great man,” people exclaimed to me. With his father, he built the first girls’ school in the village and went door to door convincing parents to allow their daughters to go to school. He also walked miles daily to a nearby town in order to attend high school, and taught himself to be proficient in English. I understood his desire for upward mobility upon seeing the house that he spent his early childhood in. He lived in a small, cobbled stone structure, the first floor of which was a stable that housed animals and the second floor of which was used for residence. It was entirely empty except for a hole in the wall where blankets were stored.

Tata recalls how my grandfather dreamed of building a large home in Baghdad for all of his children and their families, dreamed of meals together filled with enthusiastic conversation and laughter. Yet this dream died with the rise of Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, and the beginning of what would be an eight year war with Iran, sending many in the family to live elsewhere. This double displacement weighed on him and Tata.

“We had to leave Palestine,” Tata said, “then our family began leaving Iraq. We were spread across the world. Your grandfather was tired. He used to come home and say ‘I just want to go back to Palestine and die there.’ He would say, ‘maybe one day my children will be able to go back.’ He died wishing to return.”

“If I could return, I wish most of all to see Jaffa,” Tata smiled distantly, “To walk down the beach like I used to. To see my father’s house.” She added, “But even if they let me return, I couldn’t go. I couldn’t see Jaffa the way it is now, taken by the Israelis, the place I was raised gone, my family’s house gone, and my family gone, dispersed around the world. I couldn’t handle facing that.”

Yet Tata’s face filled with hope. She clasped the medallion and smiled, the gold peeking through her fingers like doves through the wires of their cage. “There must be a day when we can go back, if not our children, then our grandchildren. Inshallah [God willing].”

Sixty years later, millions of Palestinian refugees have not been able to exercise their right to return, enshrined by United Nations General Assembly resolution 194. One of the “final status” issues, a resolution concerning refugees is pivotal to reaching a peace agreement. Even Mahmoud Abbas, whose official term as Palestinian Authority president expired earlier this month, and who is a favorite of the United States and Israel, has made this clear in recent months. A resolution on refugees must include the admission of guilt by the Israeli government and a public apology, which Israel has refused in past negotiations. It must include the homecoming of refugees who wish to return to their native cities and towns that are now within the borders of Israel (polls show that this constitutes only about 10 percent of Palestinian refugees). It must include the return of refugees who desire to live in a Palestinian state. Finally, it must include reparations paid to refugee families, which Israel has refused to provide, even partially.

As the 60th anniversary of the Nakba passes, we must not allow the plight of refugees to be forgotten, buried under the inevitable snowstorms of the new year. “I know that if we ever return, it will never be the same. Some things will always be lost,” Tata said. “But to walk on our soil again and to live by our people again, to know the world didn’t forget our struggle but helped us realize our rights, this would be so much. And though some things are lost forever, maybe others will be gained.”

Editor’s note: this article originally stated that Palestinian refugees’ right to return was enshrined in UN resolution 191. The article has been updated to reflect that this right was enshrined in UN General Assembly resolution 194.

Sumia Ibrahim is an Iraqi-Palestinian residing in the United States. She is an activist for the end of the occupations of Palestine and Iraq and can be reached by email for comments and questions at sumiaibrahim AT gmail DOT com.