The Electronic Intifada 22 January 2007

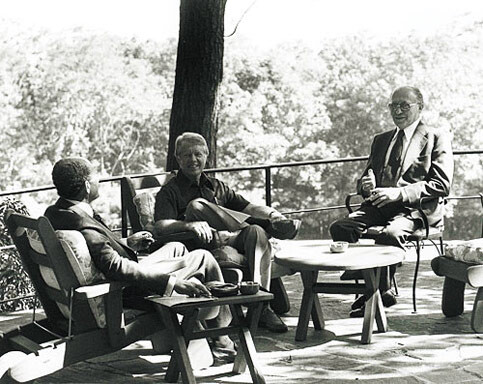

President Carter with President Sadat of Egypt and Prime Minister Begin of Israel at the presidential retreat, Camp David. (Jimmy Carter Library)

Now it’s on. The debate over President Jimmy Carter’s Palestine: Peace not Apartheid has become a mainstream staple. Turn on Fox News and see resigned Carter aid Steve Berman bullied into saying that Carter is not only anti-Semitic, but supports terror. Open the New York Times, Amazon.com, Washington Post and find outraged columnists, petitioning consumers, D-Rep. Lady Macbeth washing her hands of that dreaded a-word.

But like most things Israeli and Palestinian, few are taking note of history and what it might mean to an ex-president. Carter is no longer in “the game,” which affords him the liberty to speak frankly, unlike Howard Dean, who once hinted at criticisms of Israel before quickly retreating to behavioral protocol. Perhaps then it is fairer to judge Carter’s present in light of his past, when political cards were stacked and he spoke with another voice.

It is mid-September 1978, and President Carter has invited Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to Camp David for thirteen days of negotiation over an Arab-Israeli peace. The event was preceded by Sadat’s diplomatic visit to Jerusalem in November 1977, the first public meeting between an Arab leader and Zionist or Israeli official since the June 1918 meeting between Chaim Weizmann and the Emir Faisal. Opposition proliferated: the government in Damascus instituted a “Day of National Mourning,” Iraq canceled the celebratory Al-Adha feast, Libya withdrew recognition of the Sadat government, and Egypt’s Foreign Minister Ismail Fahmy submitted his resignation.

The Fateh party of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) issued a statement calling the visit a “dangerous turning point and a gain for world Zionism and its imperialist allies, headed by the U.S.,” and indicated that Israel had declared “on every occasion that the people of Palestine have no rights, that there can be no independent Palestinian state and no total withdrawal from occupied Arab lands.” [1]

The opposition was not without logic.

Sadat’s diplomacy validated Israel’s claim to Jerusalem as its capital, and arguably every other legal violation the state had made since occupying the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967

Sadat’s diplomacy validated Israel’s claim to Jerusalem as its capital, and arguably every other legal violation the state had made since occupying the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967. Prior to this, other countries had refused to place their embassies in Jerusalem. Even the United States’ Secretary of the Treasury, W. Michael Blumenthal, had refused to be accompanied by Jerusalem Mayor Kollek when visiting the Old City. In a sense, Sadat’s visit was the token act that Israel’s allies had been waiting for, as suggested by U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, who suddenly “had no qualms” with visiting Jerusalem in this capacity thereafter. [2]

The ironies surrounding Israel’s political leadership of the time were no less symbolic. Having broken the Labor Party’s monopoly on Israeli politics, Likud’s 1977 electoral victory brought new vigor into the colonial-settler movement in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, not to mention in Syria’s Golan Heights and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, the latter being Sadat’s primary impetus for negotiations. At the head of Likud was Begin, the former leader of the notorious Irgun Zvai Leumi militia, whose resume included an official “terrorist” labeling from the British government, and a letter from Albert Einstein and Hannah Arendt published in the New York Times describing it as “closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties.” [3]

Among Palestinians, Begin had been most recently known for “creating facts”: his repeated avowal to establish Israeli settlements in the West Bank. But more notoriously, it was Begin who, along with Yitzhak Shamir, had ordered the infamous massacre of nearly 250 Palestinian civilians at Deir Yassin on April 9, 1948. On that fateful day in Jerusalem in 1977, it was Shamir who presented Sadat to the Israeli Knesset; Sadat delivered his words, then took his seat to the right of Begin.

The political tensions leading up to Carter’s Camp David only worsened. Sadat called for a conference in Cairo, which the PLO and Syria boycotted. The Israeli officials in attendance objected to the honorary plaques set in place of the absent PLO delegates, and insisted that they be changed to read “The Arabs of Eretz Israel.” Moreover, when the Israeli delegates saw that there was a Palestinian flag flown outside the Mena House hotel (the site of the conference), they objected to “a strange and unknown flag” and had the conference organizers remove it. [4]

There is a carefulness in Carter’s description of events leading up to Camp David that warrants some attention. Begin’s involvement with the Irgun is acknowledged, but it is followed with some kind adjustments: Begin is a “man of personal courage and single-minded devotion,” yet he was “prepared to resort to extreme measures to achieve [his] goals” (41).

While Begin is given ample dimensions in Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, Sadat is described only in relation to Begin: the two were “personally incompatible,” (45) and “[a]t least with Begin, every word of the final agreement was carefully considered, and he and I spent a lot of time perusing a thesaurus and dictionary. He was a careful semanticist. He surprised me once when I proposed autonomy for the Palestinians; he insisted on ‘full autonomy’ ” (Carter’s emphasis, 46).

It is possible to re-imagine events to a point that a fiction emerges and contradictions become tolerable.

It is possible to re-imagine events to a point that a fiction emerges and contradictions become tolerable. Israeli historian Meron Benvenisti has written movingly on this. [5] In Carter’s previous work, Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President, he deals with Begin and the Camp David Accords rather differently. On the second day of the talks, Begin made it clear, according to Carter, that he “wanted to deal with Sinai, keep the West Bank and avoid the Palestinian issue.” [6] Carter later added, “I accused Begin of wanting to hold onto the West Bank, and said that his home rule or autonomy proposal was a subterfuge.” [7]

None of this is to suggest that Carter is dishonest about the events of Camp David in his new book — and Camp David certainly isn’t his central focus — but that he overlooks perhaps his greatest contribution to the subject that his book criticizes: apartheid.

Carter’s description of Camp David in Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid supports his general argument, as it is referred to throughout the book. But given the role that he played, Carter’s argument has a disembodied quality. Carter emphasizes that the Camp David Accords specified a commitment to UN Resolutions 242 and 338, which enshrined “full autonomy” and Israel’s withdrawal from the occupied territories. In concluding his section on Camp David, he laments, “The Israelis have never granted any appreciable autonomy to the Palestinians, and insisted on withdrawing their military and political forces, Israeli leaders have tightened their hold on the occupied territories” (52). He adds that if Israel had “refrained from colonizing the West Bank,” the Camp David Accords might have yielded greater success (53).

It is difficult to believe that the imminent failure of Camp David as a “peace accord” was not obvious at the time it was signed

It is difficult to believe that the imminent failure of Camp David as a “peace accord” was not obvious at the time it was signed. Prior to the talks themselves, Ariel Sharon, then head of the Ministerial Settlement Committee, told the September 9, 1978 Jerusalem Post: “Make no mistake about it, the government will establish many new settlements. That’s what it was elected to do and that is what it will do … These plans are not prejudicial to the prospects of peace …[for] they will permit us to entertain more daring solutions to the question of the Arab population than we can permit ourselves today.” [8]

Nor is it apparent that the Accords did much to uphold America’s interests in the Middle East. “Carter’s signature will cost him his interests in the Arab region,” Warren Christopher told the U.S. Department of State in a confidential cable less than ten days after the Accords were signed. [9]

Another crucial point that Carter leaves out is his direct influence on Camp David’s adherence to UN Resolutions. Camp David unfolded with the understanding that the PLO was willing to accept UN Resolution 242 on the basis that Palestinian national rights were recognized. The United States, however, rejected this, in part because of the Zionist lobby (which included popular tours made by Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan and Rabbi Alexander Schindler, along with private meetings between Carter’s staff and Dayan) and Israel’s disapproval. Throughout the talks, Carter cast frequent aspersions on Palestinians and started looking for moderates who would be willing to sign away rights. The policy document that Carter and Dayan produced after a meeting that went from 6:30 pm to 2:30 am, did not mention any Palestinian rights, and took the words “Palestine” and “Palestinian” out of the document altogether, substituting the terms with “Arab” or “West Bank and Gaza.” In its entirety, the document even contradicted the U.S.-Soviet policy approach that was established in 1977. [10]

Moreover, throughout these talks, Dayan spoke candidly about the idea of “Arab Bantustans,” borrowing liberally from South Africa’s apartheid model of the time. Added to this were Begin’s proposals for the annexation of territories without conferring upon their Palestinian inhabitants either Israeli citizenship or the political rights emanating there from. [11]

When Carter addressed Congress on the outcome of Camp David on September 18, 1978, he said that “the Israeli military government over those areas [i.e. the West Bank and Gaza] will be withdrawn and will be replaced with a government with full autonomy.” [12] In reality, “autonomy” became what one historian called a “scheme for continued occupation under a more permanent guise.” The Accords provided a series of “transitional arrangements” for the West Bank and Gaza under which Israeli military government and civilian administration would be withdrawn “as soon as self-governing authority ha[d] been freely elected by the inhabitants.” The “final status” of the territories would be negotiated by Israel, Egypt, Jordan and representatives from the West Bank and Gaza during the five-year period prescribed for the “transitional arrangements,” which were to “give due consideration to both the principle of self-government by the inhabitants of these territories and to the legitimate security concerns of the parties involved.” A U.S. official in the Jerusalem consulate later told one historian, “Neither the end of the occupation nor self-determination is fully guaranteed in Camp David.” [14]

In the fall of 1978, Israel produced a master plan that clearly stated the ambitions of future settlement and the failure of the United States to challenge them effectively

In the fall of 1978, Israel produced a master plan that clearly stated the ambitions of future settlement and the failure of the United States to challenge them effectively. According to a Ha’aretz article of the time: “The West Bankers read Carter’s words, but they believe Begin when he says that settlements in the West Bank will continue. They are afraid of becoming a minority within the borders of the autonomy.” [15] Israel would maintain control over state lands and water resources, and colonization would continue as would the development of separate legal, administrative and judicial institutions for Jewish communities, which would not be a part of the autonomy framework.

So useless were the Accords for the Palestinians that even Begin mocked it, saying that regarding Palestinian rights, it was “devoid of any real content … The word ‘legitimate’ which is linked to rights — as I tried to explain to my hosts at Camp David — has no meaning, really.” [16] Perhaps this was a slip, as Begin’s South African-born publicity consultant, Harry Hurwitz, must have told him.

Zachary Wales is a regular contributor to the Electronic Intifada.

Endnotes

[1] Jiryis, S. “The Arab World at the Crossroads: The Opposition to Sadat,” Journal of Palestine Studies in 7, no. 2, Winter 1978, 29.

[2] Ibid., 37.

[3] Massad, Joseph, The Persistence of the Palestinian Question; Essays on Zionism and the Palestinians, New York: Routledge, 2006, 3.

[4] Jiryis, Ibid., 34-5.

[5] See Benvenisti’s Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land Since 1948, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

[6] Carter, Jimmy, Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President, New York: Bantam Books, 1982, 345.

[7] Ibid., 348-9.

[8] In Aronson, Geoffrey, Israel, Palestinians and the Intifada: Creating facts on the West Bank, London; New York: Kegan Paul International, 1990, 85.

[9] Warren Christopher, Confidential, Cable State, U.S. Department of State, issued to United States Embassies and Consulates worldwide, September 26, 1978.

[10] Jiryis, Ibid., 49-50.

[11] F. Sayegh “The Camp David Agreement and the Palestine Problem,” Journal of Palestine Studies in 8, no. 2 Winter 1979, 5.

[12] Ibid, 7.

[13] Aronson, Ibid., 180.

[14] Quoted in Aronson, Ibid., 180.

[15] Quoted in Aronson, Ibid., 184.

[16] Sayegh, Ibid., 30.

Related Links