The Electronic Intifada 26 March 2025

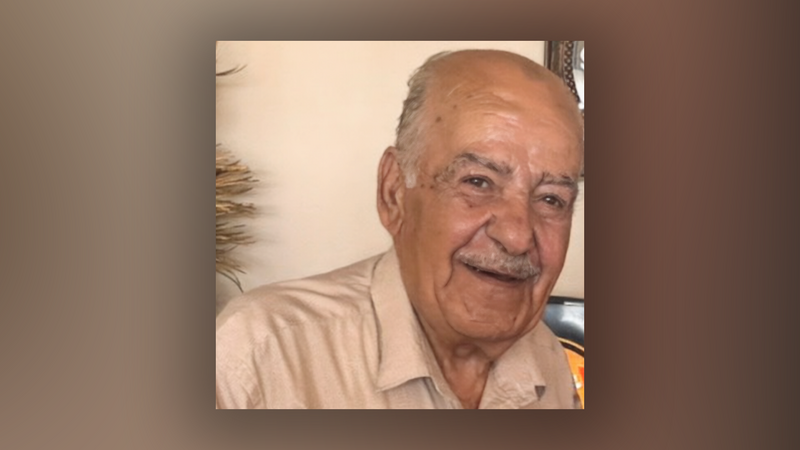

Mahmoud Orouq was born in al-Majdal in 1944 and passed away in Gaza’s Nuseirat camp in March 2024.

My grandfather Mahmoud Orouq never accepted his exile. He never wanted to leave his home in the Beach refugee camp, where he had lived for 49 years. He loved his room, with his crackers and candy box always at hand. But he had no other choice.

In October 2023, the Israeli occupation forced my nine-member family to evacuate from our neighborhood. We sought refuge in my grandfather’s home, and soon after our arrival the occupation issued more evacuation orders.

My uncle said to him, “Danger is approaching. May God be with us. The Israeli occupation forces are invading the camp and they will demolish the homes over our heads if we stay.”

My grandpa resisted, gripping the doorframe. My father and uncle and a few other men had to tell him that we had to leave the home, but even then he did not want to go.

The entire way to the next shelter, he repeated, “I want to go back to my home.”

My grandfather didn’t want to leave for many reasons, but one of the main ones was: this was not the first time he had been forced from his home by the occupation.

He was born in al-Majdal in 1944, in occupied Palestine, and in 1948 he became one of the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who were forced from their homeland during the Nakba.

He then called the Beach refugee camp in Gaza his home, where he lived with my grandmother Mariam and raised my mother and four kids.

At home in Beach camp

My grandfather and grandmother lived on the ground floor of a three-story building in the Beach camp shared with my uncles Saleh and Moatasem.

He had a diploma from Ramallah in modern mathematics, and he worked as a math teacher for many years. He was offered an engineering scholarship in Cairo, but he chose to work because he was the sole breadwinner for his family. Later on, though, he pursued a degree in history at Beirut Arab University.

His room was spacious and warm, tucked away in the corner of the house, far from the street. His study was always dimly lit, and his furniture brown. It was an old-fashioned place, with a small table where he kept his Quran and a piece of paper where he jotted down the verses he loved most.

His mobile phone was also ancient, and he refused to upgrade. Above his bed was a photograph of a landscape, perhaps a reminder to him of simpler times. He also had photos of himself as a young man on the walls.

Most important for us, as kids growing up, was the notebook he kept in his drawer. He would write puzzles for us and math games that my siblings and I would try to solve.

In the living room we would join him for tea. To him, a good cup of tea was heavy with flavor and light on sugar. He drank a strong flavor called tiger tea, and he always had a box on hand in the kitchen.

“Bless your hands”

My family and I have been displaced over 12 times since October 2023. But the first time was to my grandparents’ home in the Beach camp. We spent about three weeks there, the last large block of time I would spend with my grandfather.

These three weeks were not peaceful, and even then we had to leave the house and come back repeatedly because of Israeli bombardments. Even when we left for periods, my grandpa would stay in his room, until that night at the end of October 2023 when my father and uncle had to convince him to leave because of the imminent danger.

The airstrikes rarely stopped, and even through them, we all drank tea together. We had supplies for pastries and we made them, shaped in a mold of the map of Palestine. I made my grandfather a toasted zaatar sandwich one day, served with a cup of tea. He patted my face and said, “Bless your hands.”

My five sisters and I slept in a room, on mattresses on the floor in a room in the interior of the house.

During the day, I would stand by the front door and try to get an internet signal, to try and continue with my online work, but it was often impossible. My grandpa pulled me inside the home and told me to be careful, as he was afraid an airstrike would hit too close and get me.

One day, an airstrike did get very close to us. The building across from my grandfather’s house was bombed. It was a catastrophic day, and we survived by sheer luck.

Each displacement took its toll on him

In the year that followed, my family was scattered throughout Gaza, seeking shelter and safety.

We stayed in touch when we could, and that was difficult because the cell networks were cut off by Israel. We always asked after our grandfather’s health, and it was never good news. Each displacement took its toll on him. Since October 2023, he had been displaced four times by Israeli evacuation orders and attacks.

The last displacement was to Nuseirat refugee camp in November 2023. The cart he was traveling in with my uncle broke down – the wheel shattered because of the rough road. My uncle carried him on his shoulders until they found another cart.

My grandfather spent the last five months of his life at Nuseirat, mostly confined to a 10-square-meter room with my uncle, his wife, their three children, my grandmother and another uncle with his son. And beyond that tiny room, four other displaced families were struggling to survive under the same roof.

His peaceful routines were gone, and he found himself in this cramped, overcrowded room. Though outside was even worse, with Israeli shelling and with water and gas shortages.

He tried to cope, but with each passing day his condition deteriorated.

He passed away without granting us the chance to bid him farewell.

He died on 5 March 2024 in that room, in a home that was not his own, lying on a mattress instead of a proper bed. My grandmother Mariam sat beside him and read the Quran to him.

We learned that he died hours after the fact, because internet and cell networks were down.

We were at an internet access point – a small shop selling internet by the hour – trying to find out about his condition, when we learned that he had passed. My sister and I cried, and the people around us seemed to not pay any attention in particular. Everyone had become accustomed to war, to genocide.

A woman came up to us and asked, “Who died in your family?” as if it were all too familiar.

Expelled from his sanctuary

“When he passed, a fragrant scent filled the air,” my uncle’s wife said. “Because he didn’t just pass away, he was martyred.”

The Israeli occupation tore him away from his life and his sanctuary. It forced him into an existence he never chose.

“He never wanted to leave his home,” my grandmother said.

“We believe the displacement killed him,” my uncle added.

Like my grandpa, this genocidal war has also pushed me into a life I never chose.

I graduated in 2022, at the top of my class, with a degree in English literature. I used to start my days with online work and conversations with colleagues, and I was beginning a professional life as an English teacher.

Then my life was upended. I was cooking over fires, washing clothes by hand and unable to find even a weak internet signal. I was cut off from the world. Only now, after 15 months of hell, have I been able to even think about the future – to write again and to remember my grandfather.

We visited my grandfather’s home at Beach camp. It was still standing, though it was partly demolished. I found a fragment of his old puzzle notebook in what remained of the home. I picked it up and I still keep that tiny piece of paper close to me.

Samah Zaher Zaqout is a Gaza-based writer, lecturer at UCAS, online tutor, and translator.