The Electronic Intifada 30 December 2004

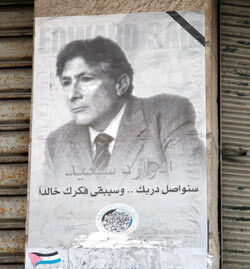

A weathered poster honoring the late Edward Said hangs in Ramallah (Maureen Clare Murphy)

However, former student D.D. Guttenplan along with director Mike Dibb convinced him otherwise. This no-frills documentary does not include archival footage to contextualize the speaker and his life; it simply records the casual conversation between Said and British journalist Charles Glass that weaves in and out of Said’s childhood, writing, life as an academic, involvement with Yasser Arafat, and his strong opinions on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

Confronted with the visage of a terminally ill Said, Glass does not hesitate to ask about his incurable leukemia. Admitting that it drained him of much time and energy, Said openly reflects that it had become a point of fixation for him. However, even as the illness and chemotherapy ravaged his body, Said found it “very difficult to turn [himself] off.” One exception was after September 11, 2001, when the media pressed him for interviews and Said knew that he did not have the strength that was needed.

When asked about his memoir Out of Place (1999), Said explains that he wrote it after the death of his mother. Born in 1935 in Jerusalem to Palestinian parents, Said was raised primarily in Cairo, Egypt, and Palestine. Recognizing his otherness in colonial Cairo, he realized that he was different from his childhood teachers, who were English, and “referred to home in a different way.” As an escape from his reality, during these years he discovered his love of literature, music and films, particularly Tarzan in which Said always identified with the colonists. In Out of Place, Said attempted to “recover these lost worlds” that had changed so much since he left as a young boy.

This sense of difference carried over into his academic training at Princeton and Yale. It was there that he discovered the intellectual influences of Plato and 18th century Neopolitan Giambattista Vico. Harvard professor Harry Levin, who was a trained comparatist, was also an important part of Said’s scholarly education. For Said, the “unlikes” drove his intellectual curiosity in literature and music. Counterpoint, which can be applied to both disciplines, is the combination of independent voices or melodic lines which establish a harmonic relationship while retaining their individuality. This comparative formula obsessed Said.

The representation of Arabs and the “other” also intrigued Said and led him to research historical depictions starting with Mohammed in Dante’s Inferno who landed in the eighth circle of hell. This also led to his tour de force Orientalism (1979), which he wrote during a fellowship at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford.

Escalating violence in Palestine, starting with the 1967 and the 1973 wars, led to Said’s growing involvement with the Palestinian cause. As a member of the Palestinian National Council from 1977-1991, Said became a close ally to Yasser Arafat. While he later would vehemently disagree with the late chairman of the PLO, Said explains that the “PLO made it possible for the Palestinians to have an identity.”

His major break with Arafat’s leadership came with the signing of the Oslo Accord in 1993 that had “nothing about the end of occupation [and] nothing about settlements of Jerusalem.” According to Said, Arafat had simply stopped caring for his people and Oslo was nothing more than a “victory for Zionism.” Arafat answered back by banning Said’s books in Palestine.

But, for Said, Arafat is not the only one to blame for the injustices done to the Palestinians. Israeli leader Ehud Barak, showed one face to the rest of the world while he actually went against the Oslo agreement. Implementing more settlements, Barak’s “generous offer” included “bits of land bounded by Israeli land … Palestinians were accepting smaller and smaller bits.”

Mixed in with Said’s condemnation of the corrupt Palestinian and Israeli leaders, is his analysis of Palestinian society. For him the main problem lies in the fact that the “intellectual class — teachers, doctors, and lawyers — never stood up to Arafat.” There are study centers in the West Bank “but people aren’t taught about Israeli society.” With the absence of role models and understanding of their occupiers the Palestinian people are also at fault.

Said spent thirty years as a professor in English and Comparative Literature at New York’s prestigious Columbia University and never thought of returning to live in Palestine. In his classroom he never taught politics, only literary classics. This distance and separation between his worlds grew out of his feeling that he “could do more in America.”

Perhaps the most captivating moments occur when Said elucidates his solutions for the future of the conflict. In a situation that is focused around land, he suggests that they must live together. “It’s fine if Israelis want a state but not at the cost of Arab lives.” Israelis and Palestinians need to “admit the existence of another people.” No matter how utopian it is, Said presses for living side by side as citizens, not separate nations. Otherwise, in terms of the Palestinians “all that’s being offered is that they negate themselves.”

Relying heavily on his memories and stories of past involvements, Edward Said’s last interview does not come across as the final words of a passionate multi-faceted man. Whether you are familiar with Edward Said’s career and writings or not, this film is an honest and enthralling tribute to a man who defied categorization and inexorably fought for truth and justice.

Jenny Gheith is currently pursuing her master’s degree in Art History, Theory, and Criticism from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Related links: