The Electronic Intifada 2 February 2016

A flock of doves flies over a tent destroyed by the Israeli military.

On the sparsely populated northern stretch of the occupied West Bank’s Jordan Valley live tens of Bedouin families.

Neglected by both the Palestinian Authority and harassed by the Israeli military, these families have to survive without running water or electricity.

Any water wells dug by the families themselves will likely be destroyed by Israel, which maintains strict control over water resources in the occupied West Bank. Israel does not issue building permits for more permanent structures. Any attempt to build such structures will likely end in demolition.

Unanswered appeals

Appeals to the PA to help Jordan Valley communities secure vital infrastructure like roads and water pipes or access to education and health care have so far been in vain. Bedouin children have to travel nearly 20 kilometers or more than 12 miles to reach the nearest schools in the towns of Tubas or Tammoun. And there are no Palestinian emergency services in the area.

“We used to welcome [PA] officials when they came with photographers and reporters,” said local resident Abdulrahim Bsharat. But 90 percent of the promises they brought have come to nothing, he said.

How hard is it for Palestinian officials to “be honest with their people?” the 66-year-old asked. He lost a son after an accident. With an ambulance arriving six hours later, the boy bled to death.

Ibrahim Ahmed Salem is tired of unfulfilled promises. The 35-year-old waited years for a solar power unit for his home, one that might allow him to watch a few hours of TV and charge cell phones. When his neighbor received one from the relevant department in the PA, and he didn’t, however, he decided there was no point in waiting any longer. He sold a number of sheep and bought his own.

The last assistance he received from the PA was 40 kilograms or nearly 90 pounds of wheat. That was in 2008.

Shrinking land

Sheepherders for many generations, the Bedouins have seen the space for their traditional livelihoods diminish over the decades since the Israeli occupation of the Jordan Valley in 1967. Israeli settlements continue expanding while the army keeps appropriating territory for training or as closed military zones, excluding those who have long lived and farmed there.

These practices and settlement expansion have led to the demolition of hundreds of homes and the “temporary” displacement of whole Bedouin communities. Under the latter practice, communities have been repeatedly uprooted — sometimes every few days.

Israel has made little secret of its determination to hang on to the Jordan Valley under any final political agreement it would strike with the PA leadership, and it has built large agricultural settlements along the stretch that borders Jordan.

According to the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem, 97 percent of the Jordan Valley is off-limits for Palestinian use. This is almost 25 percent of the total area of the West Bank.

In January, Israel announced it was annexing 154 hectares or 380 acres of agricultural land just next to Jericho and on the northern tip of the Dead Sea. It marks the largest land appropriation since 2014, when Israel purloined 400 hectares or nearly 1,000 acres of land to the Gush Etzion settlement bloc outside Bethlehem.

Text by The Electronic Intifada. Images and reportage by West Bank-based photojournalist Mohammad Alhaj.

A family stands near their tents and sheep pens.

Used glow sticks litter agricultural land after Israeli military training maneuvers near Bedouin tents.

Bashaer, 7, right, and her sister Waed Bsharat, 10: “We go to school in Tubas. I stay close to my sister when I am scared,” said Bashaer.

Bashaer Bsharat, 7, is in the first grade. Here she stands between the tents where she lives with her parents, amid the family’s clotheslines and chickens. “I like to wake up early every day,” said Basher. “I wear my plastic shoes because of the mud, to help my father in feeding and watering the sheep.”

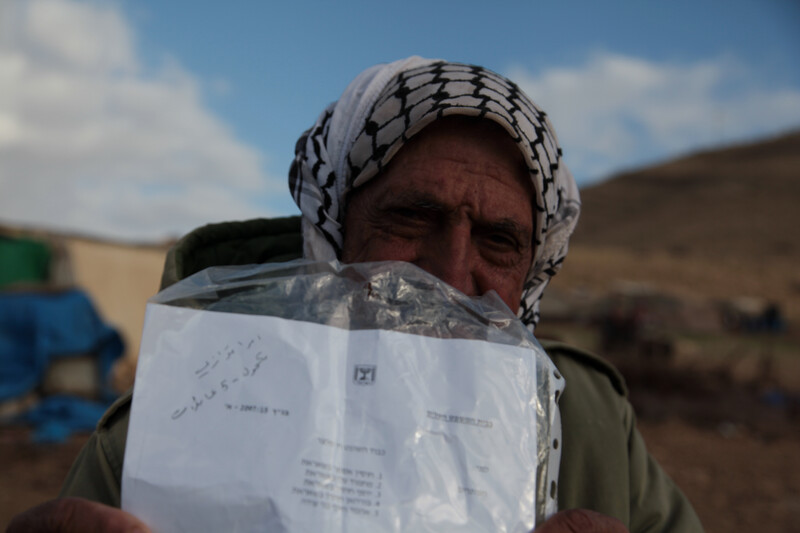

Ahmed Khalaf, 75, holds an injunction issued by an Israeli court that should have prevented his tent being demolished. In 2008, the military had ordered his tent demolished and for he and his family to leave the land. The injunction did little good. “The Israeli military did not care,” said Khalaf. “They demolished my tent in 2013.” The family pitched another tent 200 meters away. The army is still looking to oust the family from the land.

A girl helps her father tend sheep.

Yusuf and Burhan Bsharat’s sheep pens and tents.

Yusuf Bsharat, 36, is married with six children. “The problems started five years ago,” he said. “Three families here sold their sheep and moved to Tubas. Since then, the Israeli military keeps sending us notifications to leave and warnings that they will destroy our tents. They have demolished our tents many times already.”

A warning sign on Road 90 adjacent to the boundary fence between the West Bank and Jordan.

Ghaleb Fokaha, 60, was the head of a local council between 2000 and 2013. “Palestinian officials promised to help me with obtaining solar energy,” he said. “But they never came back. So I sold a number of sheep and bought solar panels for 7,000 shekels [$1,700]. We buy water from the Israelis, who have controlled the six wells on our lands since 1967.”

A girl plays near basins used to feed sheep as her family watches.

A man fills a basin with water from a tank for his sheep.

The boundary fence with Jordan.

A small solar panel and satellite dish.

Sakher Abdelrahim Hussein, 16, grazes sheep on hills near where he lives with his parents. “The Israeli military demolished our tents and barns in December 2015, while my brothers and I were on our way to school in Tubas,” he said. “We rebuilt them all. Staying on our lands bother the settlers and the military. They want to take our land to expand their settlements and army base.”

Burhan Bsharat, 40, is married with nine children. “I’m satisfied with my life but we find it very hard to get water and electricity,” he said. “Still, according to the notifications we receive from the Israeli military, we constitute a threat to the Israeli state.”