The Electronic Intifada 7 February 2017

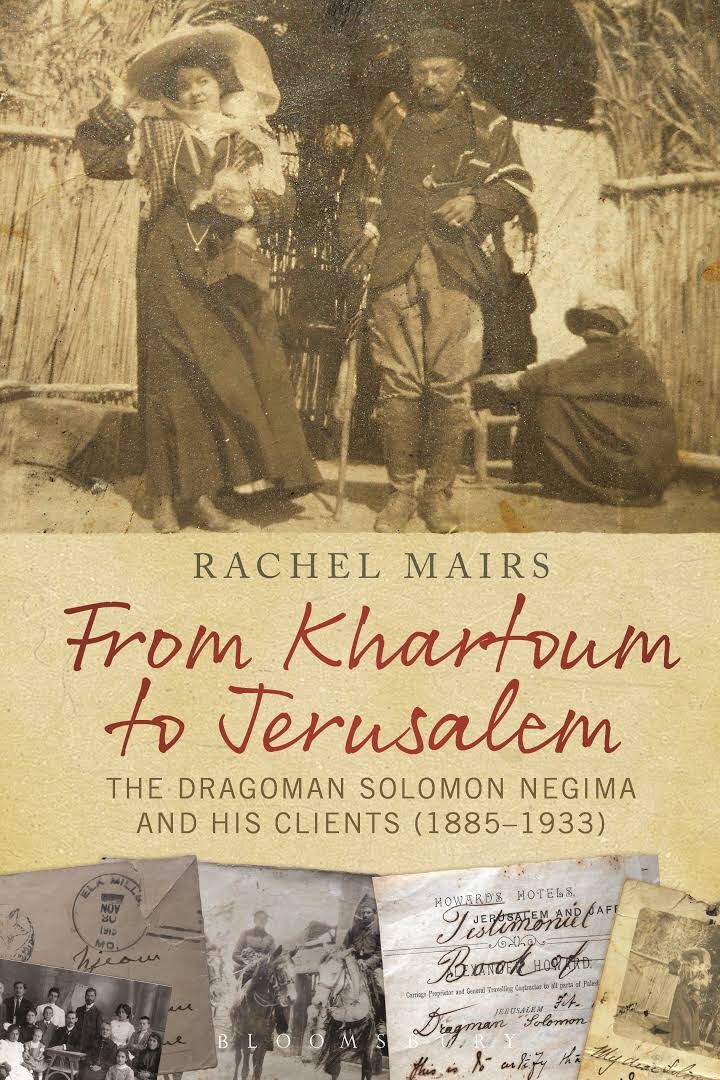

From Khartoum to Jerusalem: the Dragoman Solomon Negima and His Clients (1885-1933), Rachel Mairs, Bloomsbury (2016)

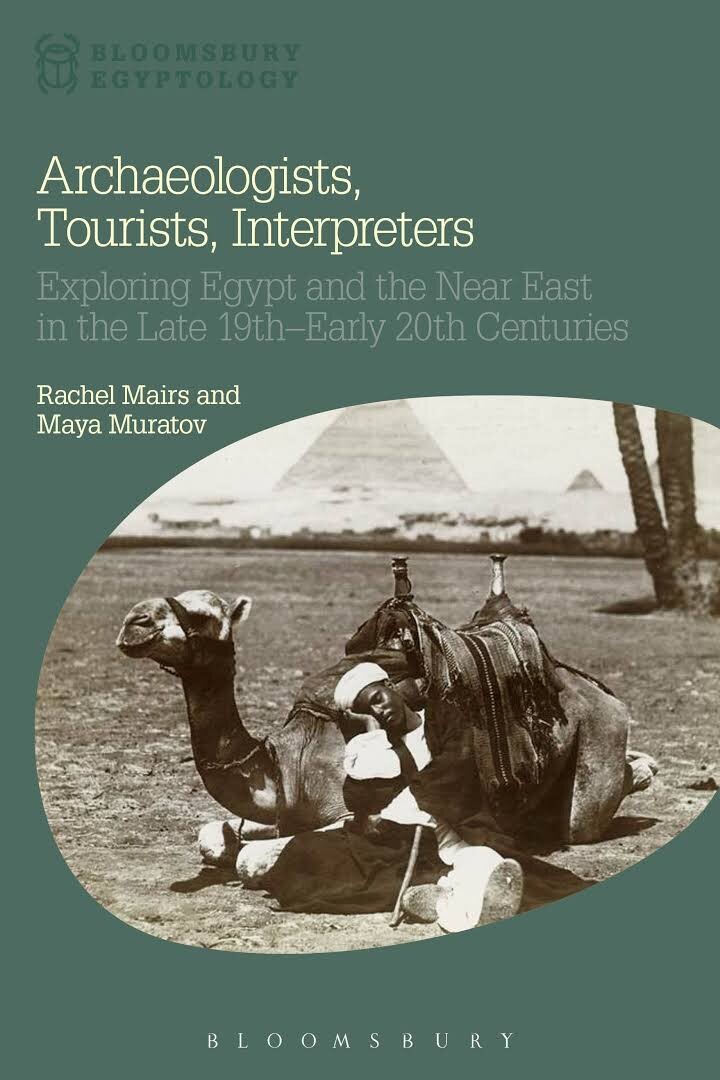

Archaeologists, Tourists, Interpreters: Exploring Egypt and the Near East in the Late 19th-Early 20th Centuries, Rachel Mairs and Maya Muratov, Bloomsbury (2015)

The beginnings of the book From Khartoum to Jerusalem are unlikely.

British academic Rachel Mairs found a collection of testimonials on eBay from the customers of Solomon Negima, a Palestinian dragoman who worked principally in Palestine and Egypt between the 1880s and the First World War. These short notes praising Negima’s work were effectively references he could show to prospective clients to emphasize his skills and trustworthy nature.

Dragomans are a feature of many travel books and memoirs of Western visitors to the Middle East, including Palestine, at this time. They were local men who acted as translators and guides for foreign tourists, pilgrims, diplomats and businessmen.

But as lower-middle-class men without prominent historical roles, their stories are rarely told. In Western accounts, they are often depicted with racist suspicion, accused of fixing high prices for souvenirs or giving inaccurate translations for nefarious purposes.

Solomon Negima was born to Christian parents; his father was probably from the Galilee area of northern Palestine and his mother from present-day Jordan. He spent most of his adult life guiding visitors based in Jaffa or Jerusalem around Palestine and, in some cases, into what are now Syria and Lebanon.

Using Negima’s collection of testimonials, Mairs pieces together the outline of Negima’s life and combines it with brief accounts of many of his customers. The effect is one of a web of acquaintances ranging from British aristocrats to early feminists, and from varied historical backgrounds – from former slaves in the American Deep South to those involved in the failed British military attempt to rescue its garrison in Khartoum from the Mahdist uprising, a religiously inspired rebellion against colonial rule in Sudan.

Amongst Negima’s clients, for instance, was the Reverend Charles Walker. Born into slavery in the American state of Georgia in 1858, he was described as “the greatest negro preacher of his time” by his death in 1921 and praised by progressives throughout the United States for his commitment to the rights and welfare of black communities.

Walker’s journey to Palestine was spurred by his religious faith and his views influenced by orientalist stereotypes, but his visit highlights the many different backgrounds of those who visited the Holy Land in the years before the First World War.

The overall result of Mairs’ effort is fascinating, reminding the reader that Late Ottoman Palestine was visited by all sorts of foreigners. While most of them arrived with preconceptions about Palestine colored by orientalism and religion, local people like Negima played an important role in how visitors saw and experienced the country, and the ideas they left with.

Just out of reach

However, the book is also frustrating. Mairs goes into some detail on Negima’s role as a translator of the ill-fated British military expedition to Khartoum and on his later life, including fatherhood, the decline of his business when he went blind and his conversion to a form of Mormonism.

But little is said about his earlier years. Mairs notes, for instance, that he may have been educated at the Syrian Orphanage, also known as the Schneller School, a major institution in Ottoman and Mandate-era Jerusalem.

Quite a lot is known about the Syrian Orphanage, the type of education taught there and the many well-known Palestinians who attended it as children. But none of these materials are used to flesh out the image of Negima’s childhood.

There is also no sense of why, if his parents lived further north, Negima ended up educated in Jerusalem, or indeed why he was in Egypt when the British army was recruiting translators for its intervention in Sudan.

Generally, Mairs’ book is a pleasurable and intriguing read, but there is a nagging sense that a fuller version of Negima’s story is just out of reach.

Defying stereotypes

In some respects, the companion book from the same research project as Mairs’ volume is a more successful offering.

Archaeologists, Tourists, Interpreters, written by Mairs along with fellow academic Maya Muratov, has a similar aim of revealing the diversity of local and foreign figures involved in intellectual exchanges in the 19th and early 20th century Middle East. But it showcases a wider range of examples, so that the slimness of background information is less of a problem.

A number of the cases described in the book are from Palestine, alongside others from Egypt, Syria and Iraq. Bringing them together highlights the overarching concern of how Western visitors encountered the cultures they met there and the ways in which local people affected those experiences.

These background ideas are explored in introductory chapters which describe some of the ways Westerners at the turn of the 20th century “met” the Middle East – through tour guides and guidebooks, hotels and language manuals (some of them written by Europeans, others by Arabs) which presented different versions of Levantine and Egyptian history and culture.

Alongside a shorter version of her material on Negima, Mairs has chapters on Flinders Petrie, the famous archaeologist who excavated in Egypt and Palestine (especially Gaza), and on T. E. Lawrence – the notorious “Lawrence of Arabia” – and his archaeological life. Muratov’s examples include the archaeologist Max Mallowan and his famous wife, the crime novelist Agatha Christie.

Muratov also contributes a companion chapter to that on Negima which tells the story of Daniel Noorian, an Armenian dragoman from Siirt in modern-day Turkey. Through his work for American archaeologists, Noorian emigrated to and studied in the US, becoming a well-known antiquities dealer.

The greater sweep of this second book, allowing for a series of case studies which illuminate different aspects of the overall theme, highlights a fascinating aspect of Middle Eastern (including Palestinian) life and culture at this time.

It defies the “Indiana Jones” image of archaeology as the work of lone white men. Instead, it shows how the Europeans and Americans who carried out excavations throughout the Middle East had their interpretations of what they saw and experienced informed by the local people who translated or taught them the language, showed them where to go and how to get there and made their explorations possible.

Sarah Irving is author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-editor of A Bird is not a Stone.