The Electronic Intifada Edinburgh 10 April 2014

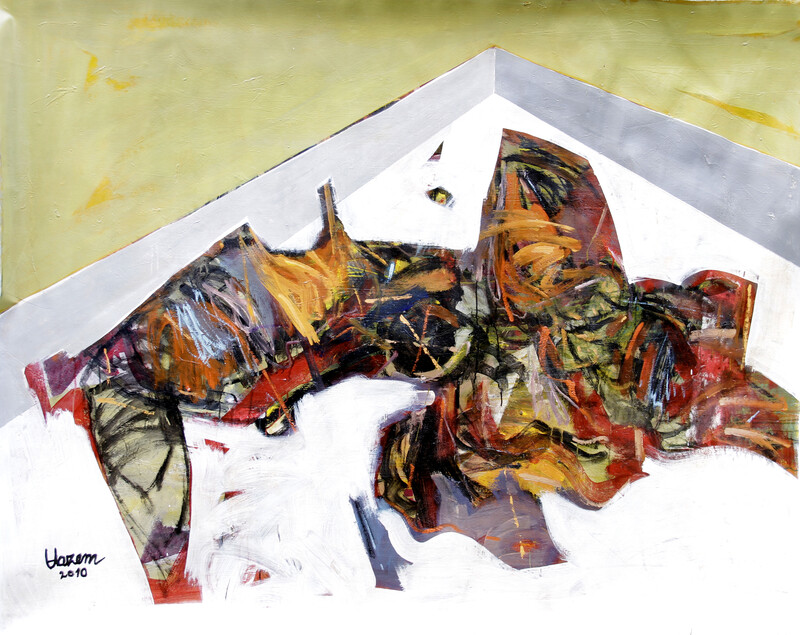

Hazem Harb, Invisibility Series #3, 108x90 cm, mixed media on collage on canvas, 2010.

A university museum in northeast England is not perhaps somewhere you would expect to find an exhibition of two of Arab art’s hottest young talents.

But in hosting Traces and Revelations, a viscerally exciting new show of paintings by Hazem Harb and Mohammed Joha, the Oriental Museum at the University of Durham has shown that Palestinian art can attract and inspire audiences outside the usual metropolitan circuits.

In a setting better known for its collections from Pharaonic Egypt and imperial China, the paintings by Harb and Joha — both from Gaza — more than hold their own. Their confident, accomplished work combines visual beauty with a questioning sensibility that is intellectually as well as aesthetically satisfying.

Harb’s contributions to the exhibition come from the Invisibility series. Several feature single or paired heads set amid washes of muted colors — grays, blues and greens. Are these lakes or deserts? Calm or drowning? All have a sense of detachment and loneliness, their identities often half-obscured.

In another image from the series, the colors brighten to pink and more of the human figure can be seen. But the arms are wrapped tightly around the body as if in pain, and the face is masked by a sheet of thick paint.

Human?

Hazem Harb, Invisibility #5, 200x160 cm, mixed media on collage on canvas, 2010.

Others show organic-looking shapes but without obviously human or animal form, sprawled across the canvas. Some are cloud-like, others resemble a limbless, faceless beast.

All are juxtaposed against blocks of color strictly delineated to create corners; the effect is strongly reminiscent of Francis Bacon’s triptychs but posing a different question. Where Bacon painted deformed, tortured humanity at the foot of the cross, Harb goes further, presenting us with things that may or may not be human.

The largest piece from the Invisibility series stands out in the farthest corner of the gallery, instantly drawing the eye as soon as one enters the museum’s foyer. This might also be a semi-creature hauling itself across a sparse room. But in this painting the “creature” seems to have been painted first and the white walls and floor added afterwards.

Up closer, it almost feels as if the reds and oranges might not be a living thing upon the floor, but a gaping chasm, blazing with the colors of hell.

Beautiful but unsettling

Mohammed Joha’s works, like Harb’s, are beautiful but unsettling in a different way. Using collages of magazine photographs and patterned paper along with often naïve images and subtle, sweet colors, he nevertheless creates images that are far from cute.

The source of the eeriness in Joha’s In X Out series of paintings is often subtle, delivered in blurred images of a little girl or a doll hanging upside-down, pigtails dangling. A doll thrown to one side or a dead child? Are the three-eyed figures showing their wisdom or are they strange and misshapen?

Mohammed Joha, Crime Scene, Series #1, 120x100 cm, acrylic on canvas, 2013.

Perhaps the most thought-provoking manipulation of the sweet and sinister in Joha’s paintings is found in Crime Scene. The title might evoke gruesome forensic TV dramas but the reality is a pastel painting which could be referencing Claude Monet’s chocolate box impressionist water lilies. Except that among the pinks and greens of Joha’s painting lurks a cat with a bird hanging limp in its mouth.

The painting’s title challenges us to wonder if this is a crime. What does it mean for the struggle for life and death to take place among the colors of paradise?

Universality

A confession from Dr. Craig Barclay, curator of the Oriental Museum and, with Arts Canteen’s Aser el-Saqqa, one of the brains behind this show, highlights the assumptions that some people will bring to Harb and Joha’s work.

“Knowing that the artist was Palestinian, I assumed that Crime Scene was about Israel — the cat killing the dove of peace,” said Barclay in conversation with The Electronic Intifada at the exhibition opening. “But when I talked to Mohammed [Joha] about it he said ‘no — it’s about Syria.’ Which shows my preconceptions.”

It is precisely the opportunity which this out-of-the-metropole show offers that seems to excite Aser el-Saqqa so much. “In ten days’ time there will be a group of forty schoolchildren coming here and looking at these paintings and making art about their responses to them,” he said. “You would never get that if you were showing these in a commercial gallery.”

Both Joha and Harb seem equally keen to stress the universality of their art.

It may come from men who grew up in Gaza’s al-Shujaiyyeh neighborhood, right at the bullseye of Israel’s military occupation. But, as Joha told the opening night audience, “This is art that is for all humanity, not for people from one nation.”

Despite the probing, questioning spirit of his paintings, Harb put his message even more simply: “Live! Love! Drink good wine! Make art!”

Sarah Irving is a freelance writer. She worked with the International Solidarity Movement in the occupied West Bank in 2001-02 and with Olive Co-op, promoting fair trade Palestinian products and solidarity visits, in 2004-06. She is the author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-author, with Sharyn Lock, of Gaza: Beneath the Bombs.