The Electronic Intifada 8 September 2015

Most literature that deals with Palestinian displacement focuses on one particular place and time. This is not so with Nahr Al-Bared (Cold River); stories are instead told from the perspectives of multiple family members who continue to feel the impact of the Nakba, the forced expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland nearly seven decades ago. They are felt by family scattered across the world up to the present day.

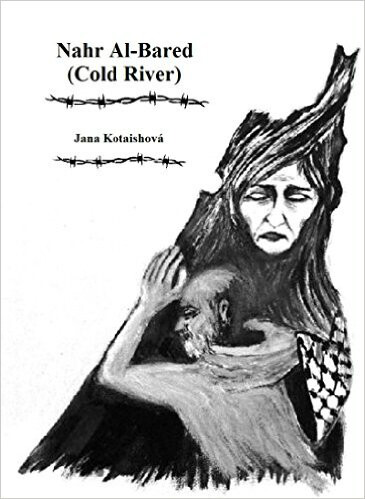

Based on true accounts, Nahr Al-Bared follows the family of Ahmed, who was born in the Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon for which this book is named. The author and Ahmed’s wife, Jana Kotaishová, compiled these narratives from her husband’s family as an acknowledgement of their struggle.

Sections are named after certain family members and the monologues throughout are written from the perspective of that person.

The beginning of the book — switching between anecdotes of Ahmed’s childhood and the youthful days of his mother and father — weaves together how Ahmed’s parents and siblings went from having “an abundance of everything” in Shefa Amr, a town in the Galilee region of northern Palestine, to being forced to live in Nahr al-Bared.

From there, the story follows the tumultuous Lebanese Civil War in which Palestinian refugees were persecuted wholesale, leading further to the constant displacement and discrimination heaped on Ahmed and his family everywhere they go. This displacement reaches as far as the current turmoil in Syria.

Hyper-personal

Accounts in Nahr Al-Bared give valuable insight into this Palestinian family’s journey into refugee status. Because they are so hyper-personal, they are particularly effective at giving the reader a better sense of history — how a mass expulsion could have been feasible, how Palestinians managed the temporary-turned-permanent refugee camps, how every upheaval in the Middle East ends up affecting them in some way.

Not long after the Nakba, Ahmed’s father Mahmoud learns that his brother and sister have managed to stay in Shefa Amr. Mahmoud and his wife Fatima sneak back across the border and are ultimately reunited with Mahmoud’s siblings. But it is not to last: Palestinians who happened to return to Shefa Amr after the initial expulsion and destruction of their homes were granted an Israeli identification card, allowing them to live there indefinitely.

Those who return too late, like Mahmoud and Fatima, are jailed, beaten and deported if caught. With no other options, Mahmoud and Fatima return to Nahr al-Bared.

This highlights the absurdity of the situation for the people who lived through expulsion while also explaining how some Palestinians were allowed to stay in the newly declared State of Israel when most were pushed out. These “on the ground” accounts of major events pepper the book.

The stories intertwine and themes are revisited. One example of this is the presence of the children of Ahmed’s brother Omar, who figure heavily throughout. The reader slowly learns of the unsatisfying marriage between Omar and his first wife, and how this leads to their children’s mistreatment.

By the end of the book, the children have become adults. But they still feel the effects of the abuse.

“You aimed too high”

The way such accounts feature so prominently in a book primarily focused on a family’s suffering after their expulsion points to another reason why it is unique. While constant displacement is a backdrop, the author also turns a critical eye toward the treatment of Palestinians in other Middle Eastern countries, as well as the sexist and antiquated parts of their own culture.

This is especially made evident in Ahmed’s retelling of his attempts to secure a civil pilot job in Lebanon.

He applies, passes multiple tests and is invited for an interview. When he arrives at the designated place, he is immediately rejected because of his Palestinian heritage. The head of the commission tells him, “You aimed too high, young man; there is no place for you up there.”

In another story, Ahmed describes his teenage infatuation with Amny, a girl who also lived in Nahr al-Bared. Forced into a loveless marriage by her parents, Amny instead falls in love with another man. This is discovered and Amny — along with her sister, who was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time — are murdered by their own father.

Ahmed, enraged by these events, “wanted to scatter the concepts embedded in the minds of our fathers and mothers, who, tooth and nail, resisted a new, freer life.”

As is probably evident at this point, this is a very intense book. Its personal nature and first-person storytelling are harrowing.

Though the subjects warrant intensity, it is a difficult book to get through.

Some of the accounts become needlessly wordy — perhaps reflecting the oral traditions behind Kotaishová’s work. This tends to drag the pace of the book down. If some of these were edited, it would give the book more focus as well as make the book itself leaner — and possibly easier to digest.

Kotaishová, as a non-English speaker, had the work translated into English from Czech. The result, while it gets its meaning across, is awkward at points.

It is also littered with spelling and punctuation errors. As a self-published book, it does not appear to have undergone a thorough proof-reading.

It is, regardless, an ambitious work that goes to great lengths to portray the real sorrow and uncertainty felt by Mahmoud, Fatima, their children and grandchildren. Fatima, in the book’s final pages, encapsulates their experience: “When we left Palestine there were two and now there are already 70 of our descendants wandering around the world.”

Marguerite Dabaie is a Palestinian American illustrator and cartoonist based in Brooklyn, New York. Her work can be found at www.mdabaie.com.