The Electronic Intifada 2 October 2017

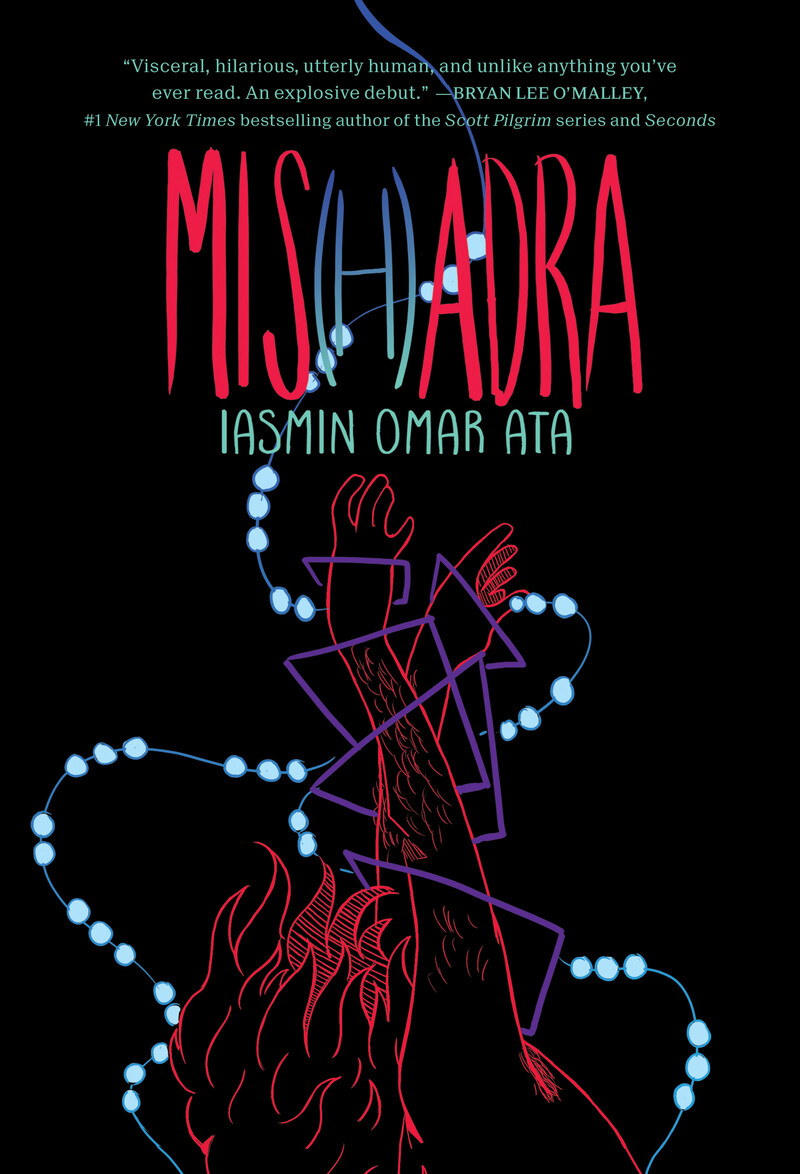

Mis(h)adra by Iasmin Omar Ata, Gallery 13, 2017

The struggle for recognition is familiar to any Palestinian. The insistence that Palestinians simply exist permeates a great deal of Palestinian cultural production.

Iasmin Omar Ata’s new graphic novel, Mis(h)adra, both asserts the existence of and is a testament to the struggles of another underrepresented and misrepresented group: people with disabilities.

These two marginalized groups – Palestinians and people with disabilities – dovetail in this book.

Mis(h)adra focuses on Isaac, a college student in New York who has epilepsy. Isaac wants to attend school and enjoy the experience like any other student. But epilepsy – and the efforts required to manage the condition – obstruct him to the point of exhaustion.

Ata’s artwork in Mis(h)adra is precise, clean and stylistically evocative of manga. Ata names the legendary Japanese manga artist Osamu Tezuka as a major influence of their work. The color choices, often contrasting, vivid and evocative of Isaac’s inner turmoil, are especially notable in this work.

Isaac’s constant battles, due to his condition as well as the attitudes toward it held by others, are presented in a complex and realistic manner.

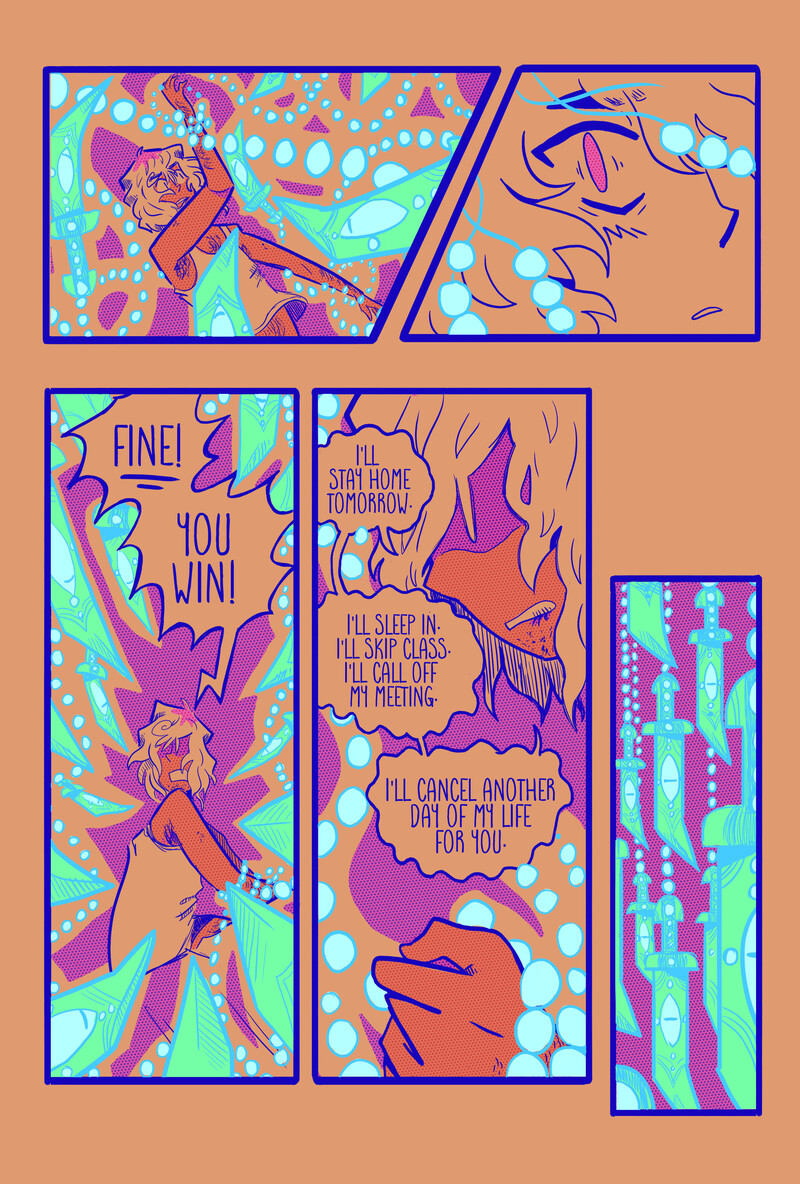

One scene depicts Isaac about to go to sleep for the night, when a large backyard party begins directly outside his bedroom. Sleep deprivation is an epileptic trigger for Isaac and he has a full schedule of classes the next day.

Isaac calls the city’s non-emergency services to file a noise complaint, only to be told it “will be handled within the next eight hours.” Isaac takes the matter into his own hands by yelling “shut up” out of his bedroom window, receiving taunts in reply.

He ultimately decides to “cancel another day of my life” by sleeping in and skipping class to avoid triggering a seizure.

Misunderstanding

Isaac encounters a great deal of misunderstanding from the people in his life.

Doctors are frequently dismissive of Isaac’s symptoms and concerns. His father, who constantly phones Isaac only to be largely ignored by his son, also displays much ignorance toward Isaac’s condition.

The rocky relationship between the two is evident in an early scene that unfolds shortly after Isaac is released from a hospital where he was treated for a seizure. Isaac explains to his father on the phone what transpired.

While it’s clear that Isaac has mentioned the seizures previously, declaring he is “sick of [him] conveniently forgetting” about his condition, his father claims, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Much of the dialogue within the comic stems from Isaac’s own thoughts. Dreamlike sequences in which Isaac turns inward, having a conversation with himself, punctuate the book.

Iconography is used to visualize what can only be felt. Stylized daggers, ghostlike and constantly lurking, depict Isaac’s seizures or the threat of an oncoming episode.

In one scene, Isaac is on a routine grocery run when he begins to feel “odd.” Dark shapes jut across the comic panels, dissecting the otherwise light space.

The darkness begins to envelop Isaac, who comments that it feels “strange” and “quiet.” The effect, which is concluded to be “a different kind of seizure,” leaves Isaac in such a state that he nearly gets hit by a truck.

Ata, who was diagnosed with epilepsy, told The Electronic Intifada that this scene is based on their own experience.

“I started having an episode of Complex Partial Status Epilepticus,” Ata said. “It’s a different kind of seizure that’s nonconvulsive and you stay in a dreamlike state, you have problems navigating.”

Living with epilepsy is not the only element of Mis(h)adra borrowed from Ata’s own life.

The use of Arabic in the title, translating to “I cannot,” is a nod to both Ata’s Palestinian heritage, as well as Isaac’s. Ata slipped Isaac’s Arabness into the story through small implications – his surname Hammoudeh, occasional bits of Arabic he speaks and the Arabic text that springs from his cell phone as a call comes in.

Palestinian identity

While Ata wanted to evoke an Arab sense in the work, it was meant to be subtle.

“The focus of the story is not the fact that he’s partially Palestinian or partially Arab,” Ata said.

“I think in a lot of works, there tends to be a push for it to be about that and I’m like, no, this character is just this person with this background going through a thing.”

Ata has more directly integrated their Palestinian identity into other work, the most recent of which is a video game and comic, both titled Being.

This short adventure game follows the story of a Palestinian from the distant future on a mission to recover artifacts from Palestine of the “past.” The story unfolds slowly and abstractly as puzzles are solved.

Ata said that the title of the game is simply an affirmation that Palestinians exist.

“We exist. That’s the title of the game, it’s just Being … It’s supposed to be simple because we are being, we are existing whether the politics of existing like it or not.”

Ata’s work goes hand in hand with their identity. It is meant not only to inform others of the existence of marginalized groups, but also to act as a balm for those living outside the norms.

Images by Iasmin Omar Ata, courtesy of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Marguerite Dabaie is a Palestinian-American illustrator and cartoonist based in Brooklyn, New York. Her work can be found at www.mdabaie.com.