The Electronic Intifada Jerusalem 4 October 2013

The anniversary of the killing of 13 unarmed Palestinian protesters inside the green line in October 2000 passed by this year without note.

APA imagesThe Palestinian calendar is permeated with anniversaries of uprisings, battles, massacres, fateful declarations and meaningless “independence” days. Despite our continuous pledge to never forget and never forgive, most of these once-paramount occasions have been transformed into fleeting memories — oscillating between irrelevance, fetishism and attempts by factions to exploit them for political gains.

For instance, the thirteenth anniversary of the start of the second Palestinian intifada passed a few days ago, but it breezed by with remarkably little public or media attention. While this is neither surprising nor unprecedented, it is exceedingly disheartening.

Although there are several negative aspects of the second intifada, it remains — for good or bad — a momentous, life-changing event for many Palestinians, particularly those of us born in the late 1980s and early 1990s. There are so many lessons we can draw from it, fatal mistakes to rue, and many disappointments and personal traumas to nurse.

One thing is certain, however. The second intifada started out as a mass popular uprising in September 2000, in which unarmed Palestinians from Nazareth to Gaza took to the streets en masse. They faced more than a million bullets, fired by the Israeli army and police in the first three weeks of the intifada alone, and they shattered the pretense of stability that the Oslo accords endeavored to maintain.

I write from a personal perspective, knowing that the process I underwent with the eruption of the second intifada was one experienced by many Palestinians — specifically Palestinians who hold Israeli citizenship and live within the green line, Israel’s internationally-recognized armistice boundaries.

Apolitical

Growing up in an apolitical, conservative family, I paid relatively little heed to politics and to the Palestinian cause. Occupation slowly strangles all Palestinians, but the extent of its effect and visibility varies from one area to another.

The few occasions I dared express my abhorrence of the Israeli occupation publicly — without understanding at the time the big words I was using — I would be reproached by my teacher or parents. Even when I summoned up the courage to call a radio show to speak about the anniversary of the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre, two weeks before the outbreak of the second intifada, I had to hide it from my parents for fear of retribution.

“They will kick you out of school and put us in jail if you criticize this state,” my over-protective father would warn. He had spent his childhood under the Israeli military rule that governed Palestinians inside the green line between 1948 and 1966.

And even though some of my parents’ fears stemmed from excessive paternalism and may have been blown out of proportion, it is not difficult to understand where they were coming from.

After all, Palestinians inside the green line are not gullible enough to buy into the myth of Israeli democracy. They are fully aware of the repercussions that political activism entails. They have witnessed innumerable examples of Israel arresting and persecuting Palestinians simply for exercising their right to freedom of expression.

The wall of fear erected by Israel since 1948 through a long process of dominance, isolation, soft power and naked violence appeared too solid for Palestinians to dismantle. The second Palestinian intifada, though, caused major holes in this wall, if only momentarily.

No wishful thinking

Remembering the massive demonstrations that took place inside the green line in the fall of 2000 brings shivers down my spine. For once, the talk of national unity was not just wishful thinking or a pointless cliché.

The demonstrations truly brought Palestinians together. Probably for the first time, we as 1948 Palestinians (Palestinians with Israeli citizenship) felt relevant and part of the conversation. We did not just watch the news and comment about a Palestine so close, yet so far away from us. We actually made the news.

For many, it was their first encounter with live ammunition and snipers. “For the first time, Nazareth appears on TV for something other than the Christmas mass,” joked a friend at the time.

It was no longer possible for school administrators to silence students. We talked about the events of the second intifada during the first week of October 2000 in class and during breaks. We argued with our teachers, some of whom insisted on lecturing us about the importance of demonstrating in a “civilized” manner.

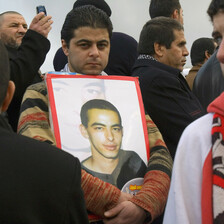

The funeral processions for martyrs Iyad Loubani, Omar Akkawi and Wissam Yazbak, the three Palestinian protesters murdered by Israeli police in Nazareth, turned into mass protests. Some of my relatives who never cared about politics attended them.

“The killing of these men by the Israeli occupation transcended politics;” “it’s a national cause, they are our sons”: these phrases were often repeated by people from neighboring villages.

Israeli police would kill a total of 13 unarmed Palestinian demonstrators inside the green line over the course of eight days that month, most of them shot in the upper body at close range. There was no criminal investigation launched into the killings, nor were any of the police held to account.

Fallacy of a free press

The strike and protests in October 2000 endowed us with an invigorated sense of national belonging. The coverage of the protests by Israeli media which described protesters as rioters and extremists spreading bedlam dispelled the fallacy that Israel has a free press.

The strong Israeli consensus on the “need” to meet protests with lethal power also proved, yet again, that Israel’s “left” is not essentially different from the right. We understood that Zionism has unleashed a tyrannical, racist regime against Palestinians everywhere, whether they live in Gaza, Jenin or Nazareth.

Unfortunately, the 1 October 2000 anniversary commemorations have become a folklore event, filled with dull speeches by political leaders. The demonstration that marked the thirteenth anniversary in Kafr Manda in the Lower Galilee was almost a copy of most previous anniversary protests in different towns. And the number of demonstrators had decreased.

Any attempt to break from this annual routine is hindered by the internal bureaucracy of the High Follow-Up Committee for Arab Citizens of Israel, to the dismay of Palestinian youth activists.

Inseparable

The problem does not just lie in the way we mark the second intifada inside the green line, however. Local political leaders and the media tend to refer to the mass protests inside the green line during October 2000 as the “October outburst,” treating them as if they were somehow separate events from the second intifada and as if they were only relevant to Palestinians with Israeli citizenship.

The October 2000 protests inside the green line were an inseparable part of the second Palestinian intifada. Though short-lived, those protests smashed the barriers which divide Palestinians and isolate 1948 Palestinians from Palestinians living in Gaza and the West Bank.

And the October protests, like the second intifada in general, did not happen solely because of Ariel Sharon’s invasion of the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem. The act of the former defense minister, who would be elected prime minister the following month, was a provocation. But there were long-festering social and political catalysts.

While it is true that the second intifada can in no way be compared to the first intifada — which was built on grassroots mobilization, self-organization and sustained civil disobedience — it is important to remember that the second intifada was born out of the post-Oslo reality and a radically different Palestinian society.

Opium

Oslo has turned the Palestinian struggle for liberation and self-determination into a bid for quasi-statehood and created a situation where Palestinians were forced to rely heavily on foreign aid and the opium of “civil society.”

Israel’s control of Palestinian water and other natural resources effectively minimized Palestinians’ ability to be self-sufficient. So they left their work in their farms and took jobs with the Palestinian Authority.

Twenty years later, Palestinians continue to pay the heavy costs of the Oslo accords that were forced on them. Israel’s theft of our natural resources has only hastened along with the settlements and the reliance on foreign aid.

Palestinian Authority leaders Mahmoud Abbas and Salam Fayyad have overseen a “state-building” project. It has included a rapacious neoliberal onslaught on the economy, the disarming of Fatah’s armed wing, the persecution of other armed resistance factions in the West Bank and the targeting of nonviolent dissidents.

All of this, as well as the geographical separation between Gaza and the West Bank, has meant that any possibility of a sustainable, inclusive grassroots rebellion has become a far-fetched dream.

For Abbas’ Palestinian Authority and its backers, such a rebellion is a nightmare they will do anything to prevent.

If the second intifada has taught us one thing, however, it is that uprisings could happen at the most unpredictable of times and that we should never be deceived by the supposed stability.

Budour Youssef Hassan is a Palestinian anarchist and law graduate based in occupied Jerusalem. She can be followed on Twitter: @Budour48.