The Electronic Intifada Arrabeh 7 October 2014

Israeli police arrest a protestor during a demonstration by Palestinian citizens of Israel in the northern city of Nazareth, against the summer assault on Gaza, 21 July.

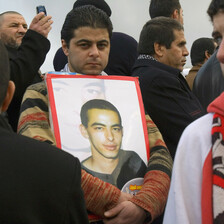

ActiveStillsJameela Asleh, better known as Um Aseel, witnessed the killing of her eldest son Aseel one October fourteen years ago when Israeli police opened fire on unarmed Palestinian demonstrators in Israel.

“I witnessed his execution with my own eyes,” the 62-year-old mother told The Electronic Intifada.

Just seventeen years old at the time, her son was among the thirteen Palestinian citizens of Israel killed during demonstrations that spread throughout present-day Israel in early October 2000.

Taking place in the Galilee towns of Nazareth, Sakhnin and Arrabeh, the protests were a response to Israel’s extreme military violence against Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, particularly the killing of twelve-year-old Muhammad al-Dura in Gaza a few days earlier.

“My son was part of the protests that exploded suddenly due to the shock of Muhammad al-Dura’s murder and [also] when [then Israeli Prime Minister Ariel] Sharon stormed al-Aqsa mosque [in Jerusalem],” Um Aseel said, referring to the two events often cited as the triggers for the second Palestinian intifada at the end of September 2000.

Violent attitude

An estimated 1.7 million Palestinians carry Israeli citizenship and live in Palestinian areas of cities, towns and villages across the country. They face dozens of discriminatory laws that limit their access to state resources and muzzle political expression, says Adalah, a Haifa-based legal center.

Worse still, Palestinian activists and human rights groups say police brutality has continued unabated.

“During protests in the ‘48 territories [present-day Israel], especially recently, the violent attitude of police forces is clear from the start,” Farah Bayadsy, a Jerusalem-based lawyer and activist, told The Electronic Intifada.

“They always start with racist talk or pushing, but then it turns into harsh grabbing or hitting,” explained Bayadsy, who is originally from Baqa al-Gharbiyya, a Palestinian town in the Triangle region of present-day Israel.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re a male or female, elderly or a student — the police violate the law and basic human rights by taking advantage of their power given to them by their blue suits,” Bayadsy added.

Um Aseel said her son was passionate about “finding reconciliation” between Israelis and Palestinians.

In 1997, Aseel became active in Seeds of Peace. That group, which organizes summer camps for young Palestinians and Jewish Israelis, has been criticized by many Palestinians for promoting “normalization” of the injustices they face.

“He participated in many programs,” his mother recalled. “He went to Switzerland and Jordan for coexistence programs. He had been very active for the five years leading up to [his death].”

“He was a quiet, calm and smart child,” she said. “He had never been in a fight before because he got along with everybody. Though he participated in the Israeli-led Seeds of Peace delegations, he always asserted his Palestinian identity.”

When a bullet fired by an Israeli police officer struck Aseel in the neck during the October 2000 demonstration, he was wearing a Seeds of Peace t-shirt.

No justice in Israeli courts

As police began attacking the protests in Arrabeh, Um Aseel felt uneasy and rushed out of the house to bring her son home. “I saw him and yelled for him to come home,” she said. “I saw a police officer hit him on the head with a rifle, and then he shot Aseel at point-blank range.”

When asked what motivated her son to join the protests that day, Um Aseel said: “What are we supposed to do? Sit in the house and say this is the will of God? Our protests and efforts to resist are the way we refuse accepting this oppression.”

The Israeli government subsequently appointed a panel to investigate the killings of the thirteen Palestinian citizens of Israel, as well as a Jewish Israeli woman and a Palestinian from Gaza during the nationwide protests.

That panel, the Or Commission, failed to arrive at a conclusion about who was responsible for Aseel’s death. Though it “reprimanded” the police for a lack of preparation and Palestinian political leaders in Israel for alleged incitement, no indictments were ever issued for the killings.

Um Aseel said “there is no justice whatsoever” for her son or “Palestinians anywhere, especially not in Israeli courts.”

“There is no such thing as Israeli justice,” she added.

Coinciding with the fourteenth anniversary of the October 2000 massacre, Adalah released an alarming new report. Between 2011 and 2013, 93 percent of 11,282 “complaints filed against the police were closed by Mahash with or without investigation,” according to the report, referring to the police investigation unit that works under the auspices of Israel’s justice ministry.

Adalah’s report paints an image of the Mahash police investigation unit as incapable of seeking justice for the country’s Palestinian minority.

More than 72 percent “of the files were closed without an investigation based on one of three reasons afforded by [Israeli] law: lack of public interest, lack of guilt, and lack of evidence,” the report states.

The report also notes that Mahash, supposedly designed to ensure police accountability, repeatedly closed cases when the excessive use of force was evident, “undermining the primary purpose for which it is created.”

Police “willing to be brutal”

Salah Mohsen, a spokesperson for Adalah, said these statistics send a clear message to anyone who dissents in Israel. “The sheer number of complaints alone says that police are willing to be very brutal,” he told The Electronic Intifada.

In numerous cases when Adalah filed complaints to Mahash with “clear evidence, such as photos, videos and testimony,” the files were closed without investigation, he said.

“Many people don’t bother filing complaints anymore,” Mohsen concluded, adding that there is a “huge need for restricting Mahash as a body if the goal is genuinely to end police brutality.”

During Israel’s 51-day attack on the besieged Gaza Strip this summer, hundreds of Palestinians in present-day Israel were subjected to police violence and arrested in demonstrations in cities such as Haifa, Akka (Acre), Jaffa and Nazareth.

But the ever-present threat of police violence didn’t stop Palestinians from assembling in Sakhnin on Wednesday last week to commemorate the fourteenth anniversary of the October 2000 massacre.

Jamal Zahalka, leader of the Balad political party, said it was important for Palestinians in Israel to continue marking the anniversary each year because the slayings “are part of Israeli policy, showing that in a time of crisis we [Palestinians in Israel] are enemies and not citizens.”

The Israeli authorities have “failed to provide any results in serving justice by pursuing the police responsible for the killings or the decision to kill,” Zahalka told The Electronic Intifada. “Many questions are left unanswered until today. The investigation was used to cover up for the criminals responsible.”

Israel’s former attorney general Menachem Mazuz closed the investigation into the 2000 killings in 2008 without issuing indictments to any police officers or commanders involved. He was recently appointed a judge in Israel’s high court.

Meanwhile, back in her Arrabeh home, Um Aseel said she will never forgive Israel for taking her son’s life.

“Aseel’s martyrdom wasn’t just aggression against him or the other twelve people who died that day,” she said. “It was an attack on all Palestinians. Israel tried to kill our humanity and make us [Palestinians in Israel] forget we are part of the Palestinian people.”

Patrick O. Strickland is an independent journalist and regular contributor to The Electronic Intifada. His website is www.postrickland.com. Follow him on Twitter @P_Strickland_.