The Electronic Intifada 19 August 2003

Israel’s immediate response has been to cancel any further releases of Palestinian prisoners and to demolish the family home of one of the bombers, as well as the homes of those families who had the misfortune of living in the same building. In the longer term, if previous practice is anything to go by, the family home of the other bomber will be demolished and Israel will insist that it can make no further concessions until the Palestinian Authority eliminates all forms of militant resistance to the Occupation.

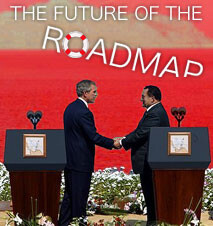

In this they can be confident of the support of the US government, which sees the Road Map to Peace in essentially the same terms as the Clinton administration saw the Oslo Peace Process: a process whereby the Palestinian Authority cooperates with Israel in disarming Palestinian militants, while the issue of Israel’s withdrawal from the Occupied Territories is left for future negotiations.

Unfortunately, this approach to peace has two serious flaws. The first is that the Palestinian police force has been crippled by three years of relentless Israeli attack and can hardly be expected to take on and destroy the militant Palestinian resistance groups — something that the Israel Army, the fourth most powerful in the world, has failed to accomplish. The second is that, after having witnessed the number of Jewish settlers in the Occupied Territories double during the Oslo Peace Process, the Palestinian people are in no mood to support such a crackdown without a clear indication of Israeli good faith.

Israel claims that it has been acting in good faith by dismantling settlement outposts and releasing of Palestinian prisoners but the facts behind the public relations reveal a different story.

Since the commencement of the ceasefire (which applies only to Palestinians) on June 29, Israeli soldiers and settlers have killed 17 people (including 7 children), wounded 437 (including 88 children), arrested 593 people, confiscated 4,457 acres of land for Jewish settlements, bulldozed 987 acres of farmland, destroyed 12,462 trees and destroyed or damaged 253 houses.

Israel claims that such actions are carried out for security reasons, implying that they are necessary to defend Israelis from Palestinian terror attacks but the term security has become so broadly defined that the claim is difficult to sustain.

From January to April this year I worked as the Media Coordinator for the International Solidarity Movement (ISM) — an international peace group, working for Palestinian human rights. On 30 July I returned to Israel to resume work. Upon arriving at the airport, I was immediately incarcerated in an immigration detention centre, pending my expulsion from the country. During my court hearing the court was cleared so that prosecution team, which included Ariel Sharon’s legal advisor and three Shabakh (secret police) officers, could present their “secret evidence” as to why I should be expelled from Israel.

What had I done to deserve such treatment? While working as Media Coordinator for the ISM, I had provided eyewitness reports of the murders of an American and a British peace activist in the Gaza Strip and the attempted murder of another American activist in Jenin. In all these reports the witnesses had insisted that Israeli soldiers had acted with a clear intent to kill, contradicting Israeli Army claims to the contrary. I also reported many other atrocities against non-combatants, which the Israeli government clearly would have preferred to have gone unreported.

Although nothing I did broke any Israeli law, the expulsion order was upheld for “security reasons” and I was deported from the country six days after my arrival.

Citing security reasons, Israel is currently endeavouring to seal the Occupation through the construction of a “Security Fence” through the West Bank, at the cost of US$1 million per kilometre. This concrete wall, which Israel claims is necessary to prevent Palestinian terrorists infiltrating into Israel, is being built well within the West Bank and has already separated an estimated 95,000 Palestinians from their farmlands, which will presumably be appropriated by Jewish settlers.

Optimists point out that President Bush himself has expressed concern about the wall and might even cut aid to Israel if the Wall continues to encroach upon Palestinian land. Other commentators are more sceptical. In November the President will begin campaigning for the 2004 election and will be counting upon the support of America’s Moral Majority, a key Republican constituency, to get re-elected. Its leaders, the Reverends Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, believe that the settlement of the Occupied Territories by Jews and the expulsion of Palestinians from Greater Israel are necessary preconditions for the second coming of Christ and are calling on President Bush to unconditionally support Israel.

So is there any hope for the Road Map?

From its conception, many analysts dismissed the Road Map to Peace as a public relations exercise to restore the credibility of America’s Middle East policies, following its invasion of Iraq. Should it fail, it might be worthwhile for its architects to assess the reasons for its failure. Like all American-sponsored peace initiatives to end the conflict, the Road Map is underpinned by the assumption that security for Israelis and ending the Occupation can be dealt with as separate issues.

Perhaps it is time to reconsider this assumption?

Michael Shaik is former Media Coordinator for the International Solidarity Movement. A version of this article first appeared in the Canberra Times on 15 August 2003.