The Electronic Intifada 10 June 2007

The separation wall near Qalandia checkpoint, between Jerusalem and the West Bank city of Ramallah, 28 December 2006. (Fadi Arouri/MaanImages)

Just days before 5 June’s 40th anniversary of the start of the June 1967 war, some of the biggest names in British architecture signed a petition calling on Israeli architects and their fellow professionals to stop participating in the creation of “facts on the ground”, which obliterate the idea of a viable future Palestinian state.

The petition, organised by London-based Architects and Planners for Justice in Palestine (APJP), condemns “three typical projects that make Israeli architects, planners and design and construction professionals complicit in social, political and economic oppression, in violation of their professional ethics.” The three projects are the E1 plan to expand the largest illegal settlement — Ma’ale Adumim — to link it with metropolitan Jerusalem, and developments in the village of Silwan and the deserted village of Lifta.

The signatories include Charles Jencks, Will Alsop (Stirling Prize winner in 2000), Ted Cullinan, Rick Mather and Sir Terry Farrell. The president of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Jack Pringle is also a signatory as are former presidents Sir Richard MacCormack, Paul Hyett and George Ferguson and president-elect Sunand Prasad.

In all, more than 260 architects, planners, academics and others have signed the petition, from countries including Britain, Israel, Palestine, Australia, the USA, Japan, Cuba, Brazil, Finland and the Netherlands. The petition was published as an advertisement in the London newspaper The Times; the full version can be seen (and signed) on the APJP website at www.apjp.org.

Coincidentally, the issuing of the petition came as the London Independent newspaper reported that Theodor Meron, who was the Israeli Foreign Ministry’s legal adviser in 1967, still believes he was right to warn the Israeli government after the 1967 war that it would be illegal to build Jewish settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories. Judge Meron is now one of the world’s leading international jurists.

The APJP petition asserts that the actions of Israeli architects and planners working in conjunction with Israel’s policy of building illegal settlements on Palestinian territory are “unethical and contravene professional codes of conduct and [International Union of Architects] UIA codes.” It says it is time to challenge the [Israeli Association of United Architects] IAUA and for the Israeli government to end such projects, and calls on the IAUA to adhere to UIA codes. APJP calls on the IAUA “to declare their opposition to the inhuman Occupation, and to end the participation of their members and fellow professionals in creating facts on the ground with a demographic intent that excludes and oppresses Palestinians.”

The petition has been sent to UIA President Gaetan Siew, IAUA President Anda Barr and to the Israeli Housing Ministry. A copy has also been sent to Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s office.

APJP says this is the first time Israeli architects have been directly challenged in this way. As APJP chairman, the architect Abe Hayeem, put it to SaudiDebate: “The occupation is an architectural enterprise, with the separation wall, settlements and the matrix of control — bridges, tunnels, checkpoints and complex terminals.” The occupation projects are perpetuating apartheid, with all settlements built within a matrix of separation. The terminals — including the Kalandia terminal — are elaborate architectural constructions.

Crucially, the petition has been signed by a number of Israeli individuals and organisations, such as the head of Bezalel Academy’s architecture department Professor Zvi Efrat, the architect, author and scholar Eyal Weizman, the director of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD) Jeff Halper, Zochrot director Eitan Bronstein, director of BIMKOM (Planners for Planning Rights) Shmuel Groag, director of the Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST) Malkit Shoshan, graphic designer David Tartakover (winner of the Israeli prize for design in 2002) and professor of geography at Ben Gurion University Oren Yiftahel.

Palestinian signatories include architect Haifa Hammami (the secretary of APJP), architect and professor at Al-Quds University Osama Hamdan, architects Fahmi Salameh and Nadia Habash, and the director of the Ramallah-based NGO RIWAQ — the Centre for Architectural Conservation, Suad Amiry.

The petition has aroused criticism from Israel’s supporters. The chief executive of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, Jon Benjamin, told the Guardian newspaper: “What they are saying is that they have a certain view and that Israeli architects must publicly declare that to be their position as well.” Benjamin said that Israeli Arabs and Jews were working together on numerous low profile but worthy projects in the Occupied Territories, and that “the two sides should be encouraged to work together.”

When the Guardian article was republished by the Israeli daily the Jerusalem Post and on the Ynetnews website it attracted a host of hostile comments from readers accusing APJP, British architects, and the British in general of anti-Semitism. Many of those posting comments assumed that APJP was calling for a boycott of Israeli architects — although the petition makes no mention of a boycott — and drew parallels between the petition and the boycotts of Israel called for by organisations of British academics, doctors and journalists. Jerusalem-based Infolive.tv website said that “anti-Israel and anti-Semitic bias and one-sidedness has often been cited by observers as prevalent in the British media and academic world. ” There were also negative reactions in the blogosphere; one blogger compared the British architects to Nazi architect Albert Speer.

“The IUA principle states that architects ‘shall respect and help conserve the systems of values and the natural and cultural heritage of the community in which they are creating architecture. They shall strive to improve the environment and the quality of the life and habitat within it in a sustainable manner, being fully mindful of the effect of their work on the widest interests of all those who may reasonably be expected to use or enjoy the product of their work’.”An article in the British weekly magazine Building Design quoted Michael Peters, founder and chairman of the international branding consultancy Identica, as warning: “British architects are going to burn their bridges with a number of developers — Israeli, British and European.”

Peters, who has worked extensively with Israeli architects, alleged that British architects do not understand the situation in Israel. “Getting involved in a lobby group can only do a disservice to the whole architectural profession” he said. “To accuse [Israeli] architects of being complicit is nonsense.”

But Abe Hayeem told Building Design that his fellow architect supporters were “pretty courageous” and insisted that architects would not be deterred from backing causes they supported. British architect Will Alsop strongly defended the petition, saying it is “not against Israel, it’s for Palestine”. Alsop said: “I think the Palestinians are living in a prison and they deserve better than that. I’d like fellow colleagues in Israel to feel some responsibility about this shabby treatment. Architects are a fairly humanitarian lot and perhaps they could help.”

For architects to be supportive of APJP can potentially have adverse career repercussions, as was dramatically shown by the volte face of one of Britain’s most famous architects, Lord Richard Rogers. When APJP was set up in February 2006, its inaugural meeting took place in Lord Rogers’ offices in London and Lord Rogers made some introductory remarks.

But within weeks Rogers publicly dissociated himself from the group, dismaying APJP and its sympathisers. His U-turn came after powerful pro-Israeli interests in New York threatened him with the loss of his commission for the $1.7 billion project to expand the Jacob K. Javits Convention Centre in Manhattan because of his links with APJP. The late Senator Javits was an ardent supporter of Israel. Other Richard Rogers Partnership projects in New York were also threatened.

Rogers at first said he was dissociating himself from APJP because of its published aims and “in view of the suggested boycott by some members,” although APJP denied it was promoting a boycott. He said he had only hosted the APJP meeting as a favour to Abe Hayeem. Rogers subsequently enlisted the services of legendary New York PR man Howard Rubenstein and hardened his line, coming out with statements defending Israel’s right to build its separation wall. He described the Israel-Palestine conflict as being between a “terrorist” state and a “democratic” one and said that he was “all for the democratic state”.

Despite this initial setback, APJP has proved effective in mobilising opinion within the architectural profession in Britain and worldwide. As in its latest petition, it strengthens its arguments by focusing on specificities in addition to stating its broad ethos and aims. In Silwan, one of the three projects detailed in the APJP petition, 88 Palestinian homes are under threat of demolition as part of a development for ultra-religious settlers from the El ‘Ad movement. Silwan is part of East Jerusalem, whose annexation by Israel after the 1967 war is considered illegal under international law.

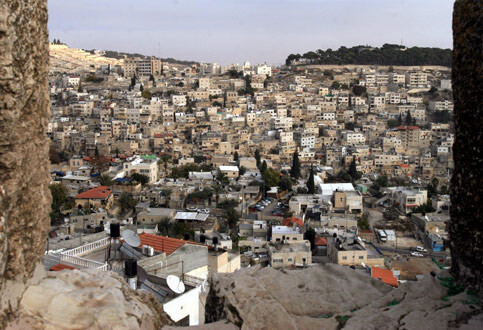

The Arab neighborhood of Silwan in East Jerusalem 7 December 2006. (Magnus Johansson/MaanImages)

The Ministry of Housing for the Jerusalem District and Jerusalem Municipality appointed the Jerusalem office of the Israeli architect Moshe Safdie to prepare a Master Plan for the southern slopes of the Old City. The plan includes the Silwan neighbourhood of Al-Bustan in which the 88 threatened houses are located, near the archaeological site of biblical Siloam.

The planned area — termed the historical ‘City of David’ — is the brainchild of El ‘Ad, a fundamentalist settler group which has been buying and expropriating houses in Palestinian neighbourhoods for many years with the tacit approval of the Jerusalem mayoralty. APJP points out that the EU has condemned the development, and that the Silwan plan contravenes the spirit and letter of the Road Map. The Road Map states that Israel should end actions including the confiscation and demolition of Palestinian homes and property as a punitive measure or to facilitate Israeli construction.

APJP is coordinating its call on Silwan with local Israeli and Palestinian architects and NGOs including BIMKOM, ICAHD, FAST, Ir Amim (City of Peoples), ACRI (Association for Civil Rights in Israel), Bat Shalom and ARIJ (Applied Research Institute of Jerusalem).

The second project highlighted in the petition concerns the deserted village of Lifta. The 4,000-year old village lies just outside Jerusalem and its last Palestinian inhabitants were killed or driven out by the Israeli Army and the Irgun in 1948. Today it is more or less a ghost town frozen in time, with its former inhabitants scattered between East Jerusalem, Ramallah, Jordan and the US.

APJP describes the campaign to save Lifta as “a plea against architectural erasure and the destruction of memory. While Israel proudly preserves its biblical heritage and archaeological sites, the rich Palestinian heritage is being allowed to disappear or deliberately destroyed.”

A renovation project by architect Gabriel Cartes of the Groug-Cartes firm, in collaboration with Ze’ev Temkin of TIK projects, aims to turn Lifta into an expensive and exclusively Jewish residential area, mainly for Americans. It would have 300 luxury flats, a large hotel, a big mall and a large tourist resort. Hundreds of pre-1948 Palestinian homes would be destroyed to obliterate any reminder that the area was once a prosperous Arab town. APJP says this is “a process amounting to cultural vandalism.”

APJP is supporting the Israeli group FAST in the campaign to preserve Lifta. Israeli organisations Zochrot and BIMKOM have also opposed the Lifta Master Plan. APJP’s petition asks for Lifta to be retained as a ruin or a memorial as a reminder of its real past or — preferably — to be allowed to be re-inhabited by survivors or descendants of the original residents. Either way, survivors and descendants should be consulted. Four generations later the descendants are still protesting for the right to return: the APJP petition has been signed by a number of “Liftawis”.

The area between East Jerusalem and the Israeli settlement of Ma’aleh Adumim outside Jerusalem in the West Bank, 28 April 2006. (Inbal Rose/MaanImages)

APJP says the project contravenes the Road Map and blocks any future possibility of a contiguous Palestinian state by cutting off East Jerusalem from the rest of the West Bank, and cutting off the northern part of the West Bank from the southern part. “This deliberate violation of the road map and the Oslo accord forestalls any basis for negotiating land for peace. When complete, the total area of Ma’ale Adumim and E1 will be 55,000 dunums — an area larger than Tel Aviv in the heart of what should have been a Palestinian state.”

In calling on the IAUA to stick to International Union of Architects (UIA) codes, it particularly has in mind the principle in the UIA charter on obligations to the public. This principle states that “architects have obligations to the public to embrace the spirit and letter of the laws governing their professional affairs, and should thoughtfully consider the social and environmental impact of their professional activities.”

The principle states that architects “shall respect and help conserve the systems of values and the natural and cultural heritage of the community in which they are creating architecture. They shall strive to improve the environment and the quality of the life and habitat within it in a sustainable manner, being fully mindful of the effect of their work on the widest interests of all those who may reasonably be expected to use or enjoy the product of their work.” IAUA is a member of UIA, as is RIBA, and it is possible that the issue of IAUA members’ alleged contraventions of the UIA’s charter will be raised at the UIA council.

APJP’s activities have inevitably aroused controversy, including its petition last September addressed to the organisers of the 10th International Architecture Biennale in Venice asking them to consider withdrawing the Israeli pavilion. The petition argued that the Israeli pavilion “totally excludes the Palestinians who are the target and real victims of the seemingly unending series of wars being memorialized, and awards Israeli the sole position of victim and victor.”

The Israeli pavilion, funded by the Israeli government, consisted of 15 memorials built between 1949 and 2006 to commemorate Israeli military war dead or the Holocaust. The Israeli Defense Ministry provided substantial support.

In an interview during the Biennale the eminent British architect, critic and writer Charles Jencks said the problem with the pavilion was that it had no place for the Palestinians who are “not allowed to commemorate or memorialize anything in their past that has been repressed, such as the 560 villages, towns and cities which have been destroyed and wiped out.” Jencks acknowledged that “architects can’t be heroes”, but asked: “How do we as architects not become complicit with power and a negative national situation? … I don’t believe architects willingly knew they were letting themselves in to be an arm of the Israeli defence department, but that is the way it has come out.”

Jencks alluded to the tensions between some Israeli and other architects when he said that he had discussed APJP’s objections to the Israeli pavilion with Moshe Safdie, one of Israel’s best-known architects, but Safdie had failed to see his point of view. “Moshe Safdie says he’ll never speak to me again, he hates me for saying this. I still regard him as a great architect and a friend.”

Israeli architect Eyal Weizman, founding director of the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmith’s College, University of London, is a strong supporter of APJP and has over the years produced a body of work of much relevance to the organisation. In his latest book — Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation — to be published shortly in London by Verso, Weizman “unravels Israel’s mechanisms of control and its transformation of the Occupied Territories into a constructed artifice, in which natural and built features function as weapons and ammunition with which the conflict is waged.” He “lays bare the political system at the heart of this complex and terrifying project of late-modern colonial occupation.”

Susannah Tarbush is a London-based British freelance journalist and consultant.

This article was originally published by SaudiDebate.com and is republished with the author’s permission.

Related Links