The Electronic Intifada 12 April 2011

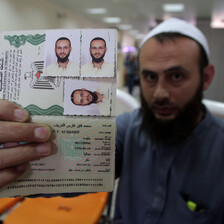

Palestinians in Gaza wait to leave through the Rafah Crossing into Egypt. (Wissam Nassar/MaanImages)

CAIRO (IPS) - Two months since the ouster of longstanding president Hosni Mubarak, Egypt’s new transitional government is turning its attention to unpopular Mubarak-era foreign policies — with the ongoing Israeli-Egyptian blockade of the Gaza Strip top of the list.

“There are strong indications that Egypt’s approach to the Gaza Strip will change as Egyptian foreign policy increasingly comes into line with popular opinion following the January 25 Revolution,” Tarek Fahmi, political science professor at Cairo University, told IPS.

In 2006, Israel sealed its border with the Gaza Strip after resistance movement Hamas swept democratically-held Palestinian legislative elections. One year later, after Hamas seized control of the coastal enclave from the US-backed Fatah movement, Egypt closed the Rafah terminal — the only crossing along its 14-kilometer border with Gaza — to human and commercial traffic.

The blockade, now entering its fifth year, has hermetically sealed the territory off from the rest of the world, depriving Gaza’s roughly 1.8 million inhabitants of many basic commodities and humanitarian supplies. Gaza is also subject to frequent Israeli attack: within the past four days alone, 19 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli air strikes and artillery barrages.

Following Egypt’s recent revolution, the Rafah crossing was opened up to Palestinian students, medical patients and expatriates. However, construction materials — especially cement — remain banned from being taken to Gaza from either Israel or Egypt.

Ever since Israel’s devastating three-week-long assault on the territory in 2008-2009, the Gaza Strip has remained in dire need of reconstruction. Along with killing more than 1,400 Palestinians, the assault completely or partially destroyed tens of thousands of homes, the vast majority of which have yet to be rebuilt.

“We’re not looking for charity or handouts,” Kanan Said Obaid, chairman of Gaza’s Association of Engineers, told IPS. “We want cement with which to rebuild destroyed homes and infrastructure.”

Under Mubarak, Egypt’s foreign ministry justified its position by referring to a 2005 US-sponsored security pact between Israel and the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority. According to that agreement, the Rafah crossing could not be reopened until a contingent of EU “observers” — who had quit the border following Hamas’ takeover — returned to their posts.

But since Mubarak’s 11 February ouster, after which Egypt’s Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) assumed executive authority over the nation’s affairs, there have been signs that Egypt’s Gaza policy — which remains enormously unpopular among vast swathes of the Egyptian public — now stands on the verge of change.

“It is unbecoming of Egypt that its foreign policy be characterized by … grave violations of the basic rules of international law, as is the case with Egypt’s stance on the siege of the Gaza Strip,” Nabil al-Arabi, Egypt’s new, SCAF-appointed foreign minister, wrote in the 19 February edition of independent daily Al-Shorouk only days before his appointment.

The five-year-old blockade, Arabi conceded, “contravenes the rules of international humanitarian law,” which, he went on to note, “prohibits the siege of civilians — even in times of war.”

Notably, on 29 March, a foreign ministry spokesperson announced that Egypt was conducting “a review of the Rafah crossing to take all necessary action to achieve greater convenience and alleviate the suffering of Gaza residents.”

The ministry’s statements were put to the test late last month when a group of Egyptian activists attempted to enter the Gaza Strip via Rafah with ten tons of cement. Activists camped out at the crossing for a week awaiting permission to enter the territory, but authorization from Cairo failed to materialize.

“Ultimately, we were barred by the Egyptian authorities from bringing the cement into Gaza,” 37-year-old activist Tamer Azzam told IPS. “This serves to confirm that Zionist, Mubarak-era policies vis-a-vis the Gaza Strip remain intact.”

According to Fahmi, who is also director of the Israel desk at the Cairo-based Center for Middle East Studies, Egypt’s foreign ministry “is still in the process of studying means of reopening the Rafah crossing.” He went on to note, however, that “such major policy changes will take time.”

“Under Mubarak, Egyptian foreign policy was the polar opposite of public opinion,” Fahmi explained. “But in post-Mubarak Egypt, Cairo’s official position can be expected to gradually fall into line with the popular will, as the government is freed from the bureaucratic and ‘security’ constraints that had characterized the former regime due to the latter’s close relationship with the US and Israel.”

He added “And Gaza will be the litmus test of the new government’s ability or willingness to translate the will of the people into official policy.”

One indication of this gradual change, Fahmi noted, was that, following Mubarak’s departure, the Gaza file was officially transferred from the Egyptian intelligence services to the foreign ministry.

“This means that Gaza has gone from being a security issue, as it was under Mubarak, to a strictly political issue,” he said. “And as such, the Gaza file — if we are to institute true democracy — must eventually come to reflect the will of the Egyptian people, who overwhelmingly want to see the siege ended and the Rafah crossing opened.”

Egypt’s transitional government has also appeared more open to Hamas than was its predecessor. In late March, Hamas officials visited Cairo, where they held their first official meeting with members of the SCAF.

Following a closed-door meeting with Arabi, Hamas’ Foreign Minister Mahmoud al-Zahar told reporters that his Egyptian counterpart had informed him there would soon be a “shift in policy” vis-a-vis the Rafah border crossing. Al-Zahar went on to refer to “the new positive spirit and obvious change in policy” since Mubarak’s departure.

Under Mubarak, Egypt had adopted a tough stance towards Hamas, an offshoot of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood (which had itself been outlawed under Mubarak). At the same time, Egypt had allied itself closely with Hamas’ West Bank-based rival, Fatah.

“The Mubarak regime took a hard line towards Hamas while being very friendly towards Fatah, a fellow client of the US,” said Fahmi. “After the revolution, by contrast, Egypt can be expected to show much more even-handedness between the two Palestinian factions.”

Cairo is planning to receive Khaled Meshal, head of Hamas’s Damascus-based political bureau. Meshal last departed Cairo more than a year ago, saying that neither he nor any other Hamas official would return to Egypt as long as Mubarak held the reins of power.

All rights reserved, IPS - Inter Press Service (2011). Total or partial publication, retransmission or sale forbidden.